EXTRACT FROM:

UNITED STATES ARMY IN WORLD WAR II

The Technical Services

THE MEDICAL DEPARTMENT:

MEDICAL SERVICE IN THE

EUROPEAN THEATER OF OPERATIONS

by

Graham A. Cosmas

and

Albert E. Cowdrey

CENTER OF MILITARY HISTORY

UNITED STATES ARMY

WASHINGTON, D.C. 1992

CHAPTER XII

A Time of Adversity

In the early morning darkness and fog of 16 December 1944 three painstakingly marshaled German field armies attacked the weakly defended Ardennes sector of the First Army front in Belgium and Luxembourg. Over 250,000 troops with 1,000 armored fighting vehicles and 1,900 artillery pieces, in 25 armored and infantry divisions, took part in this desperate counterstroke, for which Hitler and his military advisers had been planning and preparing since the late summer. The Germans intended to pierce the thin American line in the Ardennes, a wooded, hilly sector used by the First Army, with most of its strength concentrated farther north for a drive toward the Roer River, to rest battle-worn divisions and to introduce green ones to combat. Mechanized columns then were to cross the Meuse River and capture Liege and Antwerp. If successful, their drive would destroy many Allied units; disrupt supply lines; and, Hitler optimistically believed, induce the British and Americans to break their “unnatural” alliance with Communist Russia and make peace on terms acceptable to Germany.1

The enemy achieved complete surprise. Aided by several days of fog, rain, and snow, which kept the Allied air forces out of the battle, and by unorthodox tactics, including the use of special commando units disguised in American uniforms and civilian clothing, the Germans made their initial breakthrough and gained considerable ground. They destroyed one American infantry division, effectively crippled two others, and eliminated an armored combat command; and they killed, wounded, and captured thousands of American soldiers. Nevertheless, the German advance almost at once fell behind schedule, slowed by the narrow roads and difficult terrain and by the tenacious resistance of the American front-line units.

On the northern wing of the offensive the Sixth Panzer Army, with a substantial component of SS troops, supposedly the main breakthrough force, pushed back but failed to rout the 2d and 99th Infantry Divisions on the right flank of the American V Corps. These divisions, rapidly reinforced by

1The following summary of operations is drawn from Hugh M. Cole, The Ardennes: Battle of the Bulge, United States Army in World War II (Washington, D.C.: Office of the Chief of Military History, Department of the Army, 1965), passim, and Ruppenthal, Logistical Support, 2:25-26. The German plan, in fact, was over ambitious and even under the best of conditions could not have been carried to success with the available forces.

394

AMERICAN VICTIMS OF THE MALMEDY MASSACRE

others, held firm around Elsenborn and fixed the northern shoulder of the developing “Bulge.” Kampfgruppe Peiper, an advance element of the 1st SS Panzer Division, extricated itself from this fighting early on 17 December and drove 20 miles into First Army territory, in the process massacring over 100 American prisoners near Malmedy, but the U.S 7th Armored Division came in behind Kampfgruppe Peiper to hold the St.-Vith road junction for six crucial days. This division and the units that rallied around it held up the advance of most of the Sixth Panzer Army, while other American elements isolated the Peiper force and broke it up.

The Seventh Army, on the far southern wing of the German attack, soon was brought to a standstill by the rightmost VIII Corps formations, which held the longer portion of the American line in the Ardennes. In the center of the VIII Corps front, however, the Fifth Panzer Army enveloped the green 106th Infantry Division, awkwardly deployed in a salient in the Schnee Eifel (the extension of the Ardennes into Germany), capturing two American regiments, and broke through the 28th Infantry Division, a battered Huertgen Forest veteran, which was spread thin along the Our River. The Fifth Panzer Army now was in position to roll northwestward

395

toward the Meuse. Fortunately for the Americans, the 101st Airborne Division, released from SHAEF reserve, came into the gap on 19 December, just in time to deny to the onrushing Germans the important road junction of Bastogne. Completely encircled for the better part of a week, the airborne troops, aided by elements of two armored combat commands and a miscellany of artillery and support units that had straggled into Bastogne, held the town and further restricted German maneuver.

The Allied high command, although surprised by the initial German onslaught, reacted to it swiftly and effectively. SHAEF early committed its main ground troop reserve, the XVIII Airborne Corps, then recuperating after leaving the line in Holland. While the 101st Division of this corps secured Bastogne, the corps headquarters, with the 82d Airborne Division, helped extend the American line to the right of the V Corps, along the northern flank of the German salient. On 20 December, to improve coordination of the forces on both sides of the breakthrough, General Eisenhower temporarily gave operational control of the First and Ninth Armies to Field Marshal Montgomery's 21 Army Group. Montgomery was to redeploy British and U.S. divisions to stop the Germans at or in front of the Meuse and then counterattack. South of the Bulge, the Third Army took over VIII Corps and prepared to push forward to relieve Bastogne and help pinch off the salient.

The Allies gradually regained the tactical initiative, assisted mightily by a period of clear weather after 23 December, which allowed their air forces to intervene with decisive effect. The First Army shifted divisions from its left flank to its right to check the continuing German advance, bringing the Fifth and Sixth Panzer Armies to a stop well short of the Meuse. The Third Army, in a remarkable display of tactical and logistical flexibility, within days turned its axis of advance 90 degrees and attacked the enemy's southern flank. On the twenty-seventh, elements of Patton's army opened a corridor to the besieged 101st Division. The Germans had driven a wedge into the First Army front that was 60 miles deep and 50 miles wide at the base, but they had fallen hopelessly short of their ambitious objectives. During the first weeks of 1945 the First and Third Armies counterattacked in bitter cold and snow. They steadily forced back the by now exhausted, dispirited enemy. The Wehrmacht in mid-February was fighting on or behind its 16 December start line. It had left behind on the ground so briefly won over 100,000 men and uncounted quantities of equipment, and it had lost its ability ever again to resume the offensive.

For the American armies the human cost of the Battle of the Ardennes was substantial but difficult to determine exactly, due to the number of commands involved and the reporting of casualties by unit and time period rather than by engagement. According to one authoritative estimate, American combat losses in the period of the German attack, 16 December to 2 January, amounted to at least 41,000 officers and men, including some 4,100 known killed in action, 20,200 wounded, and over 16,900 missing. Many of the missing

396

likely were wounded who fell into enemy hands. First Army hospitals, between 16 December and 22 February, admitted over 78,000 patients, 24,000 of them wounded. Third Army hospitals reported some 70,000 admissions in December and January, including almost 30,000 battle casualties.2

For the field army medical service that treated and evacuated these casualties, the Battle of the Ardennes posed some unaccustomed challenges. First Army medics in units and detachments directly in the path of the German assault underwent the new and unwelcome experiences of retreat and, in some instances, capture. Medical units outside the immediate breakthrough area had to relocate in haste as the army fell back before the onslaught and then shifted forces to hold and counterattack. Surgeons with the surrounded 101st Airborne Division at Bastogne resorted to improvisation to provide emergency treatment for the growing accumulation of wounded within the perimeter, trying to keep their patients alive until they could be evacuated. Other medics with the relieving forces attempted to reinforce and resupply their besieged colleagues. The Third Army medical service, besides managing the relief of Bastogne, redeployed dozens of units and rearranged its lines of evacuation as the army swung around and attacked into the Bulge.

Medics in Retreat

The German attack for the most part missed the heaviest concentration of First Army medical units and overran few even of those in its direct path. Most of the large, relatively immobile facilities, such as the convalescent hospital and the base supply depot, were located well to the north of the breakthrough, positioned to support a renewed advance toward the Roer River. The hitherto quiet Ardennes sector held only the installations required for immediate support of the V and VIII Corps. Those installations, due to the previous inactivity of that part of the front, had a very light patient load when the assault began, a circumstance that facilitated their evacuation and withdrawal. In addition, the Germans’ mechanized exploitation of their breakthrough started much more slowly than planned; enemy armored columns did not push any distance into the American rear during the first twenty-four hours or so of the battle. This delay, besides contributing to the Germansultimate tactical failure, gave many First Army medical units just enough time to escape the blitzkrieg.3

Some medical units, nevertheless, suffered severely during the first few days of the offensive, notably those of the infantry divisions that absorbed the initial shock. On the northern shoulder of the Bulge the 99th Division and elements of the 2d fought a bitter three-day battle in woods and

2.Cole, Ardennes, p. 674; First U.S. Army Report of Operations, 1 Aug 44-22 Feb 45, bk. IV, p. 202; Surg, Third U.S. Army, Annual Rpt, 1944, ex.XXVII, and Semiannual Rpt, January-June 1945, an. XIX.

3.For an example of the light patient load, see Intervs, sub: Medical Units in vic Clervaux, in 28th Infantry Division Combat Intervs, box 24033, RG 407, NARA. Cole, Ardennes, pp. 668-71, analyzes the Germans' delay in exploitation.

397

villages, losing men and ground but denying the Sixth Panzer Army a clean breakthrough. The infantry regiments, their thin lines repeatedly infiltrated by enemy troops and tanks, their battalions at times temporarily surrounded, fell back in often chaotic combat. Their surgeons and aidmen, those of the 99th experiencing their first major action, had to cope with a number of difficulties. The cold caused even slightly injured men to go into shock so that litter squads had to carry extra blankets and aid stations had to administer larger than usual amounts of plasma. Battalion aid stations, sheltered in the crossroads villages that were a principal enemy objective, came under intense artillery and mortar bombardment. At times, medics worked on the wounded while tank and infantry firefights raged in the streets around them. The Germans, who included many SS troops, displayed less regard than hitherto for the niceties of civilized warfare. According to the 99th Division surgeon,

Medical Department soldiers were deliberately killed in spite of Red Cross brassards on both arms and four red crosses on white, circular backgrounds . . . on the helmets. It is further known that vehicles transporting wounded and plainly marked with Geneva Red Cross flags were deliberately riddled by enemy small arms fire and in one instance, a tank at close range fired an armor-piercing shell through an ambulance. . . . 4

The infantry battalions struggled to evacuate their wounded even as they fell back from position to position. As waves of attacking Germans inundated the foxhole lines, aidmen and litterbearers risked their lives to rescue every injured GI they could reach. Inevitably, wounded men were overrun or had to be abandoned; in some instances, medics voluntarily stayed behind to care for them. Most withdrawing battalions managed to bring their aid stations and their accumulated patients back with them. Battalion medical officers had first call on the available vehicles; they loaded casualties on everything that would roll and sent them out near the front of the retreating columns that groped their way, usually in darkness, along fire-breaks and winding roads. Surgeons and aidmen brought up the rear, to collect casualties of the troops covering the retreat. Losses of medics, patients, and station equipment did occur. One regimental aid station, short of transportation, abandoned its equipment to fill its truck with patients. A 99th Division infantry battalion, withdrawing from a nearly surrounded position on 17 December, discovered that it had a dozen or so more casualties than its vehicles could carry. The battalion surgeon, Capt. Frederick J. McIntyre, MC, and his detachment remained in place with these wounded men. According to the regimental surgeon, the aid station “when last seen that day . . . was being overrun by the enemy and was operating under a Geneva flag and a white flag.”5

4.Surg, 99th Infantry Division, Annual Rpt, 1944, p. 17.

5. Quotation from ibid., app. VIa. See also ibid., pp. 15-16 and apps. VIb-VIc; Intervs, Capt R. C. McElroy, Capt R. R. McGee, and 1st Battalion, 394th Infantry, in 99th Infantry Division Combat Intervs, box 24069, RG 407, NARA, which provide additional medical support details; and Medical Bulletin, 2d Infantry Division, December 1944, in Surg, 2d Infantry Division, Annual Rpt, 1944.

398

BULLET-RIDDLED ARMY AMBULANCE, a casualty of the Ardennes fighting

Although forced to retreat, the 2d and 99th Divisions held together a solid enough line to permit their medical battalions (respectively, the 2d and 324th) to maintain more or less continuous evacuation of their battalion and regimental aid stations. Nevertheless, the first days of the battle were hectic, at times desperate ones, especially for the collecting companies. The companies sandbagged their stations against the point-blank fire of infiltrating German tanks; they prepared to hold wounded for extended periods if evacuation were blocked; they hauled casualties over constantly changing, endangered routes; and they made precipitate retreats with losses in men and materiel. One company of the 324th Medical Battalion had to abandon its entire station equipment; the battalion as a whole reported eighteen men wounded or missing in December. Less heavily engaged, the 2d Medical Battalion had one of its collecting companies put out of action by materiel losses.

As division frontages contracted, the 324th Medical Battalion consolidated elements of its battered collecting companies into a single provisional unit, which evacuated all three infantry regiments. Both division clearing stations pulled back in leapfrogging sections, that of the 2d Division’s medical battalion leaving behind a significant amount of equipment. As the divisions reoriented their main supply routes from an east-west to a north-south axis, the

399

clearing companies temporarily had difficulty obtaining army medical group ambulances for evacuation. On several occasions they sent wounded to the rear in trucks. On 19 December, as the front stabilized, the 134th Medical Group reestablished reliable ambulance service between the clearing stations, now located near Elsenborn, and the army hospitals at Eupen. Thereafter, the medical services of the 2d and 99th Divisions, and of the others reinforcing the northern shoulder of the Bulge, rapidly returned to normal.6

The medical service of the 106th Infantry Division was engulfed in the catastrophe that befell that inexperienced, exposed unit. During the first four days of the offensive the entire medical complements of the 422d and 423d Infantry, the 589th and 590th Field Artillery Battalions, two engineer companies, and a reconnaissance troop—encircled in the Schnee Eifel— fell into German hands, along with their wounded, numbering in the hundreds. Details of the fate of these surgeons and aidmen are fragmentary, as are those of the entire action. The infantry regiments apparently left behind many of their aid stations, filled with nontransportable patients, during abortive breakout attempts. In the final encirclements the presence of untended wounded, and a lack of people and supplies for their care, probably hastened the surrender of the main body of the 422d Infantry and contributed to the decisions of other isolated American groups to give up.7

The 331st Medical Battalion, 106th Division, came off better. On the first day of the attack the battalion’s collecting companies kept casualties moving rearward from all three regiments, although Company A, supporting the 422d Infantry, was forced to make an early retreat by one of the encircling German columns. The following day, the extent of the disaster became apparent. Company A lost contact with the 422d and withdrew to St.-Vith. Company B, with the 423d Infantry, was surrounded and eventually captured; Company C, retreating with the division’s only surviving regiment, the 424th, evacuated its casualties during its participation in the defense of St.-Vith. The division surgeon and clearing company moved westward from their original position at St.-Vith to Vielsalm, where they handled casualties of a number of divisions blocking the advance of the Sixth Panzer Army. As the Germans gradually worked around to the westward of the St.-Vith defenders, the clearing company, on 19 December, shifted a platoon farther west to La Roche, only to have it overrun by an enemy column. The remaining 106th Division medical elements withdrew from Vielsalm on the twenty-second, as American forces under orders re-

6.For tactical developments, see Cole, Ardennes, chs. V and VI; Surg, 99th Infantry Division, Annual Rpt, app. VId; Medical Bulletin, 2d Infantry Division, December 1944, in Surg, 2d Infantry Division, Annual Rpt, 1944.

7. For accounts of this disaster, see Cole, Ardennes, ch. VII, and Richard E. Dupuy, St. Vith: Lion in the Way. The 106th Infantry Division in World War II (hereafter cited as The 106th) (Washington, D.C.: Infantry Journal Press, 1949), passim. For medical details, see pp. 129-30, 143-44, and 148-50 of the latter work. See also Surg, 106th Infantry Division, Annual Rpt, 1944, p. 4. Other medical details are in the 106th Infantry Division Combat Intervs, box 24081, RG 407, NARA.

400

luctantly gave up their St.-Vith salient.8

The 28th Division, stretched thinly over a 20-mile front immediately to the right of the 106th, gave way under the full weight of the Fifth Panzer Army assault. During the first three days of the battle the division’s two flank regiments, the 112th Infantry on the north and the 109th on the south, pulled back in reasonably good order and joined the American forces rallying on the shoulders of the breakthrough. Their surgeons and aid stations accompanied them and maintained more or less normal operations throughout the offensive. In the division center, however, the 110th Infantry was all but destroyed in delaying the enemy advance on Bastogne. Its surgeon, Maj. L. S. Frogner, MC, located with the regimental command post at Clervaux, lost all contact with his battalion aid stations during the afternoon of 16 December, as those installations were overrun or cut off in the general wreck. Frogner and his aid station were captured late the following day, after German tanks and infantry overwhelmed the patchwork of headquarters and service elements defending Clervaux.9

The division's 103d Medical Battalion, during the quiet period before the attack, had split its clearing company into three separate detachments, each of which handled casualties of a single regiment. This arrangement, adopted to save time and transportation in evacuating sick and wounded from the extended division front, fortuitously was of benefit during the German offensive. It ensured continuous clearing company support of the flanking regiments even as they became separated from the division and were attached for a time to other commands. The 103d Battalion managed to extricate all of its elements, although it lost twenty-one men captured in the retreat. Company B, the collecting company behind the 110th Infantry, had to abandon much of its equipment, as did one platoon of the clearing company. Battalion headquarters withdrew with the division command post from Wiltz to a position near Neufchateau, southwest of Bastogne.10

The V and VIII Corps surgeons reacted quickly to the emergency. They tried to extricate their corps medical battalions from danger while keeping contact with their divisions and coordinating evacuation. Colonel Brenn, the V Corps surgeon, and his medical section remained at Eupen throughout the battle, under intermittent German shelling and for a time threatened by enemy paratroopers. The headquarters, the clearing company, and one collecting company of the corps’ 53d Medical Battalion—the rear elements, ironically, as the battalion was oriented to support an American attack toward the northeast—

8.Surg, 106th Infantry Division, Annual Rpt, pp. 4-5 and encl. 7; Dupuy, The 106th, pp. 61, 89-90, 98-99. Surg, 7th Armored Division, Annual Rpt, 1944, pp. 21-22, gives additional details of evacuation from St.-Vith.

9.Cole, Ardennes, ch. VIII; Surg, 28th Infantry Division, Annual Rpt, 1944, p. 4; History of the 110th Infantry Regiment (hereafter cited as 110th Infantry Hist), sec. III, pp. 61-74, box 8596, RG 407, NARA; Intervs, sub: Medical Units in vic Clervaux, in 28th Infantry Division Combat Intervs, box 24033, RG 407, NARA.

10.Surg, 28th Infantry Division, Annual Rpt, 1944, encls. 5-6; Col. D. B. Strickler, Action Report of Germans' Ardennes Breakthrough, . . . in 110th Infantry Hist, app., box 8596, RG 407, NARA.

401

CARING FOR AN INFANTRYMAN INJURED IN THE ARDENNES FIGHTING

were in more danger; their location at Heppenbach was in the middle of the 99th Division battlefield. On 17 December the battalion, by making two trips using all available vehicles, evacuated its personnel, its 180 patients, and about 95 percent of its equipment to Eupen. The trucks had to travel over roads already under German observation, but the enemy did not interfere with them. The battalion, however, did lose three ambulances and five men in an apparent ambush during a separate evacuation mission. With his medical battalion safely repositioned, Brenn concentrated during the rest of the battle on supervising evacuation and trying to determine how many medical personnel and how much equipment his divisions had lost. 11

The VIII Corps surgeon, Colonel Eckhardt, lost contact early with the flank divisions of his hard-hit corps. His own section, with the corps headquarters, moved in haste from Bastogne to Neufchateau on 18 December and then on the twenty-first to Florenville, still further south. There, “a very unmerry christmas was faintly observed and a not very joyous New Year was welcomed.” The corps’ 169th Medical Battalion, which had its

11.Surg, V Corps, Annual Rpt, 1944, pp. 21-22; 53d Medical Battalion Annual Rpt, 1944, p. 14.

402

BRIG. GEN. JOHN A. ROGERS, DECORATING A FIELD HOSPITAL MEDIC

headquarters and clearing station at Troisvierges, close behind the center of the corps front, and its collecting companies widely spread out, with drew relatively intact and eventually reassembled near Florenville. This battalion, besides supporting the remaining units of the VIII Corps, also served the 101st Airborne Division after it moved into Bastogne.12

In addition to divisional and corps units, the breakthrough area contained a number of First Army medical installations. They included the headquarters and attached battalions of two medical groups: the 134th, located at Malmedy, which evacuated the V Corps; and the 64th, at Troisvierges, supporting the VIII Corps. Platoons of two field hospitals, the 42d and 47th, were spread across the front, receiving nontransportable casualties from the infantry divisions. Evacuation hospitals were clustered on the northern and southern fringes of the Bulge. In the north the 44th and 67th, at Malmedy, were receiving wounded from a local attack by the left-wing divisions of the V Corps. Behind the VIII Corps the 107th Evacuation Hospital, as the German offensive began, had just ceased operations at Clervaux and was preparing to move. The 102d at Echternach and

12.Quotation from Surg, VIII Corps, Annual Report 1944, p. 8. See also 169th Medical Battalion Annual Rpt 1944, pp. 10-12.

403

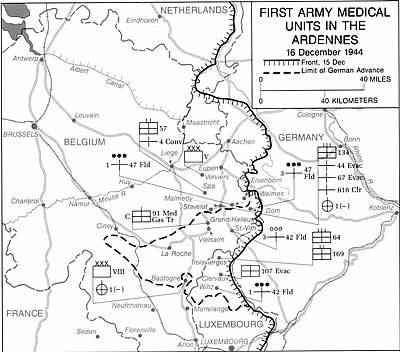

FIRST ARMY MEDICAL UNITES IN ARDENNES, MAP 17

the 110th at Esch were open for patients from the VIII Corps right wing. The Bulge also contained a couple of specialized army hospitals. At Malmedy the 618th Clearing Company operated a center for treatment of combat exhaustion casualties; at Grand-Halleux, west of St.-Vith, Company C, 91st Medical Gas Treatment Battalion, cared for malaria, contagious disease, and self-inflicted wound patients. Advance sections of the 1st Medical Depot Company maintained supply dumps at Malmedy and Bastogne.13

The First Army surgeon, Brig. Gen. John A. Rogers, MC, located at army headquarters at Spa, north of the breakthrough area, received his first hint of the enemy offensive early in the morning of 16 December (Map 17). It came in the form of reports of heavy shelling from the evacuation

13.This section is based on the annual reports, 1944, of the units mentioned.

404

hospitals at Eupen and Malmedy. Around 1900 Rogers learned that the Germans during the day had made “some penetration” of the VIII Corps line and along the boundary between it and V Corps. “A request for information to the army G-3 elicited the response that the action was thought to be local, and the penetration not considered serious.” Three hours later, however, the G-3 indicated to Rogers that the Germans attacking the VIII Corps were gaining ground. On the basis of this information Rogers gave orders for the withdrawal of the platoon of the 42d Field Hospital at Wiltz and of the 102d and 107th Evacuation Hospitals, his most exposed units in the rear of the VIII Corps. The next day, as word came of growing pressure on the V Corps, the army surgeon also began sending retreat orders to medical units in the path of the Sixth Panzer Army.14

Most immediately threatened by the German breakthrough were four field hospital platoons. In the V Corps area the 1st and 3d Platoons of the 47th Field Hospital, located respectively at Waimes and Dom Butgenbach, received wounded from the 2d and 99th Divisions. Behind the VIII Corps the 1st Platoon of the 42d Field Hospital at Wiltz supported the 28th Division clearing station; the 3d Platoon, in St.-Vith, served the 106th Division. These units, unlike the division clearing stations with which they were located, did not possess organic transportation for rapid withdrawals. Further, although working closely with the divisions, the platoons were under the command of the medical groups. In the confusion of the first days of the battle they had difficulty in obtaining timely orders and information; their movements were not always well coordinated with those of the divisions. Surgeons with the platoon at St.-Vith, for example, learned of the offensive only when the hospital was engulfed by 106th Division wounded, by which time, according to them, the division clearing station already had left for Vielsalm. The division surgeon, on the other hand, claimed that the platoon “took off” without warning, leaving him with no emergency surgical capability. On 17 December all these units extricated themselves from their exposed positions, but with a nearly total loss of equipment and, in some instances, with casualties among patients and staff. Regrouped in rear areas, they were out of action for the rest of the battle, their personnel in bivouac or temporarily attached to other medical units. 15

Two platoons, the 1st of the 47th Field Hospital at Waimes and the 1st of the 42d at Wiltz, had particularly dramatic and, in the latter case, tragic experiences. The 1st Platoon at Waimes continued working throughout the morning of the seventeenth, the staff increasingly agitated by the stories told by incoming wounded of

14.Rogers was promoted to brigadier general effective 10 November 1944. Surg, First U.S. Army, Annual Rpt, 1944, pp. 53-54, gives a chronology of the surgeon’s initial decisions.

15.42d Field Hospital Annual Rpt, 1944, pp. 4-5 and encl 1; 47th Field Hospital Annual Rpt, 1944, ans. 7-8; 64th Medical Group Annual Rpt, 1944, p. 8. On the platoon at St.-Vith, see Clifford L. Graves, Front Line Surgeons: A History of the Third Auxiliary Surgical Group (San Diego, Calif.: Frye & Smith, 1950), p. 242, and Interv (source of quotation), Lt Col Carl Belzer, 6 Jan 45, in 106th Infantry Division Combat Intervs, box 24081, RG 407, NARA.

405

overwhelming German attacks. Orders to evacuate patients and nurses preparatory to withdrawal arrived from the 134th Medical Group around midday. Early in the afternoon, the unit sent its eighteen patients off to the 67th Evacuation Hospital at Malmedy. However, when the nurses, a short time later, tried to follow the same road to the rear, they found it blocked by artillery fire and the proximity of Kampfgruppe Peiper. The women, forced by the shelling to leave the ambulance in which they had been riding, walked and hitchhiked back to Waimes. Trucks dispatched by the 134th to transport the platoon failed to arrive; but ambulances from the front, filled with wounded, did.

The 1st Platoon medics, who had packed their equipment for movement, unpacked it again, set up operating theater and wards, and went back to work. They continued treating patients until about 1100 the next day. At that time two armed Germans, one in an American uniform, appeared and announced that the hospital, and a large number of nonmedical stragglers who had collected there during the night, were prisoners. Also caught were the commanding officer of the 180th Medical Battalion, his S-3, and his driver. They had stayed behind in Waimes to help evacuate the hospital after the battalion, a 134th Medical Group unit, had withdrawn from the town. Armed Americans at the hospital considerably outnumbered the enemy, but they made no resistance for fear of compromising the installation’s Geneva Convention protection. The hospital platoon commander, Maj. Earl E. Laird, MC, talked the Germans into leaving thirty-six patients where they were, along with the nurses, four medical officers, and a few enlisted technicians to care for them. The enemy lined up everyone else to wait for trucks to carry them into captivity. Fortunately, an alert battalion ambulance driver managed to escape in his vehicle. He brought back troops from a nearby American unit, who chased away the Germans in a brief firefight. With a road to the rear now open, the 1st Platoon evacuated its patients. The personnel then headed for Spa, leaving behind all their hospital equipment but the kitchen. When the unit members reached the First Army rear, they were dispersed among several general and field hospitals for work and lodging.16

At Wiltz the 1st Platoon of the 42d Field Hospital, directly in the path of the enemy drive toward Bastogne, received no definite information or order until the afternoon of 18 December. Toward evening, with German columns already threatening to encircle the town, the 28th division passed word that the platoon should prepare for evacuation by a 64th Medical Group truck convoy that was on the way. The hospital confronted a dilemma. It had twenty-two patients whose condition was such that, under the regulations, they should not be moved. Maj. Charles A. Serbst, MC, the senior auxiliary surgical team leader, urged that these wounded men be evacuated anyway, because German captivity would be more hazardous to their survival than a truck

16.47th Field Hospital Annual Rpt, 1944, an. 7; Graves, Front Line Surgeons, pp. 247-49; 180th Medical Battalion Annual Rpt, 1944, p. 3; 575th Ambulance Company Annual Rpt, 1944, p. 9.

406

ride. The hospital platoon commander, Major Huber, however, insisted that these patients had to stay put. According to the auxiliary surgical group historian, “Serbst was right but Huber prevailed.” If patients stayed, it was First Army policy that medical personnel must remain to care for them. Huber, to his credit, adhered to the letter of this regulation also. He, with another officer and sixteen men of the platoon, and with Serbst and his auxiliary team, remained with the casualties and went into captivity early on the nineteenth, when German troops entered Wiltz. The rest of the personnel, with several truckloads of hospital equipment, left during the night of the eighteenth. The medics, running a gauntlet of American roadblocks and German fire, made their way back to VIII Corps lines. However, the trucks carrying the equipment, diverted to another mission, unloaded their cargo in Bastogne, an occurrence for which 101st Airborne Division medics soon would have cause to be grateful.17

Both medical groups moved hurriedly to escape the attack. The 134th Medical Group, which evacuated the V Corps, retreated to Spa during the afternoon of the seventeenth. This group lost several ambulance crewmen killed in the Malmedy massacre. Nevertheless, its 179th and 180th Medical Battalions withdrew generally intact and continued evacuating, respectively, the left and right flank divisions of the corps. The 64th Medical Group, supporting the VIII Corps, pulled out of Troisvierges early on the seventeenth. While an advance group command post remained with the corps surgeon at Bastogne, the balance of the unit continued on farther south to Martelange. Several more retreats followed until the group, on the twenty-first, finally reached Sedan. Four days later, as the VIII Corps front at last stabilized, the 64th Group moved to Gerouville, on the Franco-Belgian border east of Sedan, more centrally located for control of evacuation. Throughout the crisis of the battle the attached ambulance and collecting companies of these groups, in spite of frequent displacements and bewilderingly rapid changes in the divisions to be supported, managed to keep casualties moving back from the clearing stations. The groups also did much of the work of mustering trucks to move field hospital platoons and other less mobile organizations.18

On the northern edge of the Bulge the westward drive of Kampfgruppe Peiper compelled a series of medical unit withdrawals. On 17 December the 44th and 67th Evacuation Hospi-

17.The First Army considered the decision on removal of patients from an endangered hospital to be “a command function,” but insisted that “from a medical viewpoint, if patients are not evacuated, sufficient medical personnel must stay behind to care for the patients even at the risk of capture.” See Surg, First U.S. Army, Annual Rpt, 1944, p. 70. Quotation from Graves, Front Line Surgeons, p. 259. See also ibid., pp. 258 and 260-61; 42d Field Hospital Annual Rpt, 1944, pp. 4-5; 64th Medical Group Annual Rpt, 1944, p. 8; Surg, Third U.S. Army, Annual Rpt, 1944, pp. 55-56; 110th Evacuation Hospital Semiannual Rpt, January-June 1945, p. 12; 240th Medical Battalion Annual Rpt, 1944, p. 7.

18.134th Medical Group Annual Rpt, 1944, pp. 14-17; 64th Medical Group Annual Rpt, 1944, and Semiannual Rpt, January-June 1945, p. 1. For examples of the work of attached medical battalions, see 180th Medical Battalion Annual Rpt, 1944, p. 3, and 240th Medical Battalion Annual Rpt, 1944, pp. 7-10.

407

tals, the 618th Clearing Company exhaustion center, and the 2d Advance Section, 1st Medical Depot Company, retreated in haste from Malmedy, generally heading for Spa. The following day, the contagious disease and malaria hospital, Company C, 91st Medical Gas Treatment Battalion, pulled out of Grand-Halleux. All these units removed their personnel and patients, most of them in ambulances and trucks provided by the 134th Medical Group and the First Army Provisional Medical Department Truck Company. They also made much use of self-help. The 618th Company, for instance, secured rides for about half of its 200 patients by flagging down passing trucks. For lack of time and transportation, the units for the most part left in place their equipment and, in the case of the depot section, their stock. On the twenty-first and twenty-second, after the battle line stabilized just south of Malmedy, the 134th Medical Group, using vehicles and men of several evacuation hospitals, retrieved most of the outfit of the units withdrawn from that town. The depot section, by sending in a few trucks at a time, managed to haul its stores back to the base depot at Dolhain. A salvage detachment of the gas treatment company, on the other hand, came under German fire at Grand-Halleux and only secured a portion of that unit’s equipment. Regardless of how much of their equipment was recovered, the withdrawn hospitals effectively were out of action for the rest of the battle. Most had to retreat a couple of times more as the First Army regrouped. Their people remained in billets or were detailed to work in other medical installations.19

By midmorning on 18 December elements of Kampfgruppe Peiper's SS armored force had reached Stavelot, less than 10 miles by road from Spa. Few American troops then were between the Germans and First Army headquarters with its cluster of service installations. The army, accordingly, directed all logistical units in Spa, including those of its medical service, to withdraw to Huy, a city on the Meuse about 25 miles to the west, where they would be well situated either to support a new defense line or for further retreat. Army headquarters at the same time moved to the environs of Liege.

This withdrawal involved a number of working medical units and others earlier displaced from farther south. The 134th Medical Group, previously pushed out of Malmedy, joined the new exodus. So did the 57th Medical Battalion, heretofore located at Spa, which constituted the army reserve of collecting and ambulance companies and controlled the now heavily committed Provisional Truck Company. The commander of the 57th prudently had stationed liaison officers at

19.Surg, First U.S. Army, Annual Rpt, 1944, pp. 22 and 53-54; First U.S. Army Report of Operations, 1 Aug 44-22 Feb 45, bk. IV, p. 156; 134th Medical Group Annual Rpt, 1944, pp. 14-15; Surg, V Corps, Annual Rpt, 1944, p. 22; 44th Evacuation Hospital Annual Rpt, 1944; 67th Evacuation Hospital Annual Rpt, 1944, and Semiannual Rpt, January-June 1945; 618th Clearing Company Annual Rpt; 1944, pp. 5-6; 91st Medical Gas Treatment Battalion Annual Rpt, 1944, p. 5; 1st Medical Depot Company Annual Rpt, 1944, p. 7. For an example of trucks used in equipment recovery, see 45th Evacuation Hospital Annual Rpt, 1944, p. 175. For the origin of the First Army Provisional Medical Department Truck Company, see Chapter IX of this volume.

408

General Rogers' office and at other headquarters in Spa, to ensure that he would receive up-to-date intelligence and timely orders. He started his battalion off as soon as the enemy was reported at Stavelot. Most important of these new displacements was that of the 4th Convalescent Hospital at Spa. Since the offensive this large installation, besides performing its main mission of patient reconditioning, had housed and fed the personnel of withdrawing medical units. Within less than twenty-four hours the 4th disposed of its 1,400 patients, either returning them to duty or transferring them to COMZ facilities. Then the staff packed up their essential records and unit housekeeping equipment and took the road to Huy. How they managed all this in so short a time, the commanding officer, Col. John W. Claiborne, Jr., MC, was not sure; apparently, he wrote later, it was “a case of team work with all players clicking.” At first bivouacked at Huy and later at Tirlemont, the 4th could not resume operations for lack of a suitable site. Its removal from action was a crippling blow to the entire First Army hospitalization and evacuation system.20

In the VIII Corps area the 1st Advance Section, 1st Medical Depot Company, pulled out of Bastogne on 18 December. The unit was able to take along only a portion of its stock, even though it commandeered empty ambulances and the trucks that had brought the 42d Field Hospital equipment from Wiltz. A four-man detachment stayed behind with the rest of the supplies. The main body of the unit halted briefly at Libin, some 20 miles west of Bastogne, then retreated again southwestward to Carlsbourg on the twenty-first. Five days later, after the Third Army had taken over medical support of the southern flank of the Bulge, the section moved north and rejoined the base depot at Dolhain.21

Of the three evacuation hospitals in the rear of VIII Corps, two were displaced by the German attack. On 16 December the 102d Evacuation Hospital relinquished its position at Echternach, only 6 miles from the front lines, and made a long march right across the battle area to Huy, which it reached on the eighteenth. “A withdrawal of this nature,” the unit report declared, “is an experience that all the personnel will long remember.” This unit brought along all of its equipment and opened for patients on the twenty-first. The 107th Evacuation Hospital, which had been closed when the offensive started, worked while withdrawing. It first fell back from Clervaux to Libin, where it admitted over 780 patients in eighty-two hours. Assisted by a platoon of the 92d Medical Gas Treatment Battalion, the hospital evacuated 300 patients on the twenty-first, then moved with 100 more to Carlsbourg, where it partially set up again. The next day it retreated for a final time to Sedan. There, after hasty reconnaissance, the

20.Quotation from 4th Convalescent Hospital Annual Rpt, 1944, pp. 2 and 8. See also First U.S. Army Report of Operations, 1 Aug 44-22 Feb 45, bk. II, p. 120; Surg; First U.S. Army, Annual Rpt, 1944, p. 54; 134th Medical Group Annual Rpt, 1944, p. 15; 57th Medical Battalion Annual Rpt, 1944, pp. 22-24.

21.First U.S. Army Report of Operations, 1 Aug 44-22 Feb 45, bk. IV, p. 156; 1st Medical Depot Company Annual Rpt, 1944, p. 7.

409

unit found shelter in a former vocational school and resumed operations on Christmas Eve. During the following week, it handled over 1,000 patients.22

The remaining evacuation hospital in rear of the VIII Corps, the 110th at Esch, well south of the breakthrough, stayed in place. During the first week of the German offensive this 400-bed hospital received most of the American casualties from the southern flank of the Bulge, and in addition it fed and temporarily sheltered thousands of troops separated from their units. Patients arrived at a rate of about 300 a day. The surgical backlog at one time also exceeded 300. As no field hospitals any longer were in front of the 110th, these surgical patients included many men with severe chest and abdominal injuries. To cope with this influx, the hospital pitched tents in the paved courtyard of its building to house the sick and lightly wounded. The receiving section culled all the immediately transportable patients from among the incoming casualties, filled out the basic medical forms on them, and at once placed them in ambulances and sent them toward the rear. By such expedients, and by strenuous round-the-clock effort, the staff, heavily reinforced with auxiliary surgical teams, coped with the overload. The 110th handled over 5,000 patients within a month, with a mortality rate of a little less than 1.5 percent among the over 2,200 admitted for surgery.23

Medical Realignments

Even as the last medical units extricated themselves from the breakthrough area, the First and Ninth Armies were shifting forces to build a solid line between the Germans and the Meuse. The Ninth Army relinquished four infantry and two armored divisions to its southern neighbor. At the same time its XIX Corps extended to its right to take over most of the territory and several divisions of the First Army’s VII Corps, freeing the latter headquarters and its corps troops for commitment on the northern flank of the Bulge. The First Army on 19 December transferred the VIII Corps, with which its headquarters no longer had effective communication, to the Third Army for both operational control and logistical support. At the same time the First Army acquired the XVIII Airborne Corps, which went into line immediately to the right of the V Corps controlling the 82d Airborne Division and others from the Ninth Army and VIII Corps. Finally, on the twenty-fourth, the VII Corps shifted its headquarters from Aachen to Huy. With one armored and two infantry divisions it formed the right wing of an army front anchored on Elsenborn Ridge, and extending from there generally southwestward.

Medical rearrangements accompanied this reorganization. In the Ninth Army the 31st Medical Group and

22.Quotation from 102d Evacuation Hospital Annual Rpt, 1944, p. 2. See also 107th Evacuation Hospital Annual Rpt, 1944, pp. 6-8; 92d Medical Gas Treatment Battalion Annual Rpt, 1944, pp. 6-7; Surg, Third U.S. Army, Annual Rpt, 1944, p. 56.

23.110th Evacuation Hospital Semiannual Rpt, January-June 1945, pp. 3, 18, 42 and encl. 3.

410

several field and evacuation hospitals changed position to support the southward extension of the XIX Corps and to evacuate casualties of divisions formerly under the First Army. At the same time the Ninth Army surgeon, Colonel Shambora, and his staff made preparations for withdrawal in the event that the Germans extended their offensive to their army’s hitherto quiet front or broke clear through the First Army and crossed the Meuse. Shambora selected an alternate medical concentration area just east of Brussels. He redeployed two evacuation hospitals, and platoons of two field hospitals closed and pulled back. Shambora also had his forward evacuation hospitals send all their unused heavy equipment, such as tentage, back to the 35th Medical Depot Company for storage, thereby reducing the transportation requirements in any retreat. The Ninth Army front, however, remained largely inactive.24

The First Army, in addition to relinquishing its VIII Corps to the Third Army, transferred its 64th Medical Group (to include its two battalion headquarters, a collecting company, four ambulance companies, and a clearing company) and the corps’ medical battalion and one field and three evacuation hospitals. In return, on 21 December, the First Army picked up from the Ninth Army a medical battalion, the 187th, with one ambulance and three collecting companies. The companies went to reinforce the 134th Medical Group, now responsible for evacuating both the V and XVIII Airborne Corps. The army used the additional battalion headquarters, with a collecting company and a clearing company platoon attached, as a provisional medical battalion for the airborne corps, which hitherto had lacked one. During the VII Corps redeployment the 68th Medical Group, which supported the corps, moved its headquarters 50 miles; disengaged from support of five divisions and as many evacuation hospitals; and assumed responsibility for eight new divisions, belonging to the VII and XVIII Airborne Corps, as well as two evacuation hospitals. The group commander observed: “Probably at no previous time had the flexibility and ease of adaptability of a Medical Group been more clearly illustrated than during this emergency. . .”25

To the rear of the fighting line General Rogers attempted to put back together an army evacuation and hospitalization system disrupted by the rapid movement of the front and the displacement of so many medical units. Even though most threatened installations, or at least their personnel, escaped the advancing Germans, Rogers within forty-eight hours of the start of the attack no longer had enough beds in operation for normal hospitalization and evacuation of his

24.Surg, Ninth U.S. Army, Annual Rpt, 1944, pp. 10-11 and 13-16; 31st Medical Group Annual Rpt, 1944., pp. 19-20.

25.Quotation from 68th Medical Group Annual Rpt, 1944, p. 22. On 21 December the 134th Medical Group moved forward from Huy to Verviers to be closer to the V Corps. See 134th Medical Group Annual Rpt, 1944, pp. 15-16. See also Surg, First U.S. Army, Annual Rpt, 1944, pp. 54-55 and 57-78; VII Corps Medical Plan, pp. 103-04, encl. 1 to Surg, VII Corps, Annual Rpt, 1944; 187th Medical Battalion Annual Rpt, 1944, p. 2; Surg, XVIII Airborne Corps, Semiannual Rpt, January-June 1945, pp. 1-3.

411

casualties. Well over half of the First Army’s dozen evacuation hospitals by that time had closed for movement, had lost their equipment, or—in the VIII Corps area—had become inaccessible to the majority of divisions. In addition, the displacement of the 4th Convalescent Hospital, the 618th Clearing Company exhaustion center, and the 91st Medical Gas Treatment Battalion communicable disease facility left the army unable to retain and care for short-term cases. Perforce, then, Rogers on 19 December established a total evacuation policy in place of the ten-day one hitherto in effect. Under the new policy, army hospitals evacuated all their patients as soon as they were able to travel and sent new arrivals whose conditions permitted it, without treatment, directly to COMZ facilities. Most of the bypassed patients, under an agreement between Rogers and the ADSEC surgeon, Colonel Beasley, went to the by now well-developed cluster of general hospitals around Liege. Those hospitals, according to General Hawley, “saved the First Army medical service during the counteroffensive,” for without them Rogers could not have kept his remaining evacuation beds open for fresh casualties or cleared his endangered units for withdrawal.26

Two ADSEC units close to the combat zone temporarily served as army evacuation hospitals, receiving wounded brought from division clearing stations. One of these, the 77th Evacuation Hospital, a 750-bed unit located at Verviers, had been functioning as a holding unit and hastily reorganized to perform its original mission. Just behind the center of the new First Army front, the 77th, assisted for a time by the 9th Field Hospital, for about a week handled most of the casualties from divisions trying to stop the German advance toward the Meuse. The staff, augmented with auxiliary surgical teams and medics from nonoperating First Army hospitals, worked eighteen-hour and longer days to sort, treat, and evacuate the flood of patients. They keep eight operating and two fracture tables busy day and night. Verviers, a major road center, came under daily enemy artillery fire, V-1 bombardment, and Luftwaffe raids. This danger forced off-duty personnel to spend their few hours of rest in crowded, fetid underground shelters. On 20 December a shell blew off a corner of the school building that housed the 77th, wrecking a bathroom; damaging the nurses quarters, laboratory, and pharmacy, and one medical ward; and mortally wounding a Red Cross worker. The hospital staff cleaned up the wreckage and continued in operation. A week later, in addition to the regular patient influx, the 77th had to care for the 14 dead and 50 wounded from a direct bomb hit on the 9th Field Hospital. “For hours the receiving room was in a turmoil as the differentiation and treatment went on. Among the dead, decapitations and amputations made the task gruesome, even for the men who had seen many hundreds of wounded.” Enemy bombardment for a time prevented hospital trains from

26.Quotation from Ltr, Hawley to TSG, 27 Jan 45, file HD 024 ETO O/CS (Hawley-SGO Corresp). See also Surg, First U.S. Army, Annual Rpt, 1944, pp. 54, 56-57, 69-70. Some individual hospitals went to total evacuation even before the army change of policy. See 5th Evacuation Hospital Annual Rpt, 1944, p. 15, for example.

412

reaching Verviers. The Advance Section maintained evacuation of the 77th with ambulances, which shuttled patients back to the Liege general hospitals. The burden on the weary 77th staff eased only in the last days of the year, as First Army hospitals began opening in Verviers.27

The 130th General Hospital, although an ADSEC unit, lay just within the First Army area. As it turned out, this hospital, set up in a large school building at Ciney, was positioned almost exactly at the westernmost tip of the Bulge and was well placed to receive casualties from the VIII Corps. That, however, was not its function. The 130th had been reorganized before leaving England as a specialized neuropsychiatric facility. At Ciney it treated combat exhaustion casualties from the First and Ninth Armies. The hospital’s mission changed abruptly on 19 December, when ambulance loads of wounded began arriving, both from retreating evacuation hospitals, such as the 107th, and directly from division clearing stations. According to the unit report, the hospital found itself “acting as a cross between a clearing company and an evacuation hospital which required revamping . . . [the] entire setup.” The 130th discharged its exhaustion patients to an ADSEC replacement depot, sent its psychiatric staff to the rear, and enlarged its surgical service with people from the 12th Field Hospital and the 3d Auxiliary Surgical Group. Between the twentieth and twenty-third the hospital received and treated or bypassed over 3,000 patients. It evacuated most of them by train from a nearby siding. The unit performed surgery on about 200 casualties. The German advance rolled almost literally up to the door; fighting occurred in the hospital grounds as the 2d Armored Division and other units moved in to engage and throw back the enemy. On the twenty-third the 130th evacuated all but a skeleton staff and its nontransportables. The remaining staff and patients all left or were evacuated during the next four days, along with the most vital items of equipment. An armored combat command treatment station temporarily occupied the plant until the twenty-eighth, when an advance party of the 130th moved back in.28

While these ADSEC hospitals, and the few First Army ones still active, coped with the immediate flow of casualties; General Rogers tried to redeploy and reopen his evacuation hospitals. He worked within the constraints of an army G-4 order, issued on Christmas Day, to withdraw all logistical units except those absolutely essential for operations to positions north and west of the Meuse. Under this directive First Army hospitals and other medical units redeployed to a concentration area about 15 miles or so west of Liege. These included two of the three evacuation hospitals that had been working in Eupen throughout the battle, under bombardment comparable to that endured by the

27.Quotation from Allen, ed., Medicine Under Canvas, pp. 142-48. See also Surg, ADSEC, COMZ, Annual Rpt, 1944, p. 20; 77th Evacuation Hospital Annual Rpt, 1944, pp. 7-8; 134th Medical Group Annual Rpt, 1944, p. 16.p

28.Quotation from 130th General Hospital Annual Rpt, 1944, pp. 4, 11, 16-17, 28-30. See also Surg, ADSEC, COMZ, Annual Rpt, 1944, p. 10.

413

FORMER SCHOOL FACILITY HOUSING THE 130TH GENERAL HOSPITAL AT CINEY

77th at Verviers. This final withdrawal crowded First Army units back into towns already occupied by numerous ADSEC facilities. As a result, the hospitals sent there could not reopen for lack of usable buildings, tented open-field operation being out of the question in the cold wet weather. By the end of the year the First Army had a few evacuation hospitals working: the 102d and 51st (field acting as an evacuation) at Huy, the 97th and 128th at Verviers, and the 2d at Eupen. The other six evacuation hospitals then under the army, however, remained inactive, as did the convalescent hospital and most of the Specialized medical facilities. General Rogers, accordingly, kept a total evacuation policy in effect until mid-January.29

The First Army also redeployed its medical supply installations during the last week of December and began rehabilitating those of its units that had lost equipment in the retreat. Under the 25 December withdrawal order the base depot, with most of its stock, moved by rail from Dolhain to Basse Wavre, southeast of Brussels. As later described by the army surgeon, “A series of incidents, some humorous and some serious, including

29.Surg, First U.S. Army, Annual Rpt, 1944, p. 56; First U.S. Army Report of Operations, 1 Aug 44-22 Feb 45, bk. IV, pp. 144-45; 68th Medical Group Annual Rpt, 1944, p. 23; 134th Medical Group Annual Rpt, p. 16; 2d, 5th 45th, 97th, and 102d Evacuation Hospitals Annual Rpts, 1944; 51st Field Hospital Annual Rpt, 1944.

414

an international dispute as to right of tenancy, misrouted cars, and lost vehicles,” prevented supply issues from this depot for the rest of the year. Two advanced sections of the 1st Medical Depot Company kept most of the army supplied. The 2d Advance Section, earlier withdrawn from Malmedy, on the twenty-sixth set up a dump at Huy to support the army's right wing corps and divisions. At Dolhain the 1st Advance Section issued to the V Corps, and the army blood bank detachment, also located there, remained in operation. First Army medical units farther to the rear for a while drew directly upon COMZ depots, notably M-409 at Liege. By the end of the year the base depot was engaged in replenishing its much depleted stock. General Rogers sent liaison officers to divisions and other organizations to determine the extent of their medical equipment losses, which in many units approached 100 percent of their basic allowances. His office then worked directly with the chief surgeon’s Supply Division to speed replacement items forward.30

Throughout the medical unit movements resulting from the Ardennes battle, the First Army Provisional Medical Department Truck Company performed indispensable service. This unit, attached to the 57th Medical Battalion, had been formed during the pursuit by pooling vehicles, primarily taken from evacuation hospitals, as a transportation reserve for moving the larger army installations. Its work, and vehicle strength, had diminished in scope during the relatively static autumn and winter battles, but in the late-December crisis the company again came into its own. Expanding quickly from 50 trucks to Medical Depot Company kept most of 100, in two weeks it transported nine evacuation and three field hospitals the convalescent hospital with 1,400 patients, a depot company section, and a gas treatment company, as well as tons of supplies. The company significantly increased the ability of the First Army medical service to respond rapidly to the changing military situation.31

During the first two weeks of the German offensive, the First Army By medical service redeployed most of its nondivisional units while maintaining continuous evacuation of the regrouping combat forces. Its relative success in both endeavors may be attributed to a favorable starting position, to the delays in the German advance, to an abundance of transportation, and to a high standard of unit and individual initiative and resourcefulness. By the end of December, however, the army for all practical purposes had lost its ability to hold and treat casualties; its medical service perforce had been reduced to little more than a conduit between division clearing stations and COMZ hospitals.

Bastogne: Encirclement and Relief

The battle for Bastogne began on 19 December, when the 101st Airborne Division went into action to the east of that strategic road junction.

30.Quotation from Surg, First U.S. Army, Annual Rpt, 1944, p. 22. See also ibid., p. 23; First U.S. Army Report of Operations, 1 Aug 44-22 Feb 45, bk. IV, pp. 156-57; 1st Medical Depot Company Annual Rpt, 1944, p. 7.

31.Surg, First U.S. Army, Annual Rpt, 1944, p. 61; 57th Medical Battalion Annual Rpt, 1944, pp. 22-23.

415

The following day the VIII Corps gave Brig. Gen. Anthony C. McAuliffe, acting division commander, overall charge of the defense, with control also of Combat Command B, 10th Armored Division; of Combat Command R, 9th Armored Division; and of an assortment of artillery, tank destroyer, and other units that had collected in Bastogne. On the twenty-first the Germans closed their ring and made their first attacks on the American perimeter. The enemy surrender demand came on the twenty-second and elicited General McAuliffe’s immortal one-word rejection. For another four days the defenders fought off repeated assaults by the Fifth Panzer Army, making effective use of well-directed artillery fire to break up German attacks. At night they endured Luftwaffe bombing raids on the city. The American units within the perimeter had enough food, ammunition, and other necessities, brought in with them or foraged from abandoned First Army and VIII Corps dumps, to carry them through until 23 December, when large-scale supply airdrops began just in time to avert a critical shortage of artillery shells. At 1645 on the day after Christmas elements of the 4th Armored Division of the Third Army opened a road into Bastogne from the south. This breakthrough ended the siege, although heavy fighting continued around the city for several more weeks.32

American casualties during the siege amounted at least to 189 officers and men killed, 1,040 wounded, 407 sick and injured, and 412 missing—the loss reported by the 101st Division. In addition, Combat Command B of the 10th Armored Division suffered about 500 battle casualties, and there were still more among the other commands, and fragments of commands, that defended the city. The great majority of the sick and wounded were trapped in Bastogne for the duration of the encirclement.33

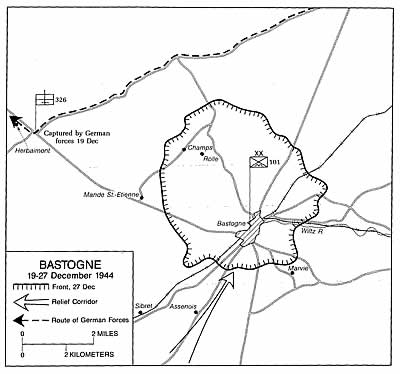

The 101st Division medical service was organized and equipped for self-sufficient operations out of contact with the normal ground chain of evacuation. Its medical detachments went into action at full strength in men and equipment and carrying along extra reserves of litters and blankets. The division's 326th Airborne Medical Company included both collecting and clearing elements and had an auxiliary surgical team attached so that it could perform the functions of a field hospital platoon (see Map 18).

An early stroke of misfortune deprived the division of its hospital. The 326th Company, accompanied by the division surgeon, Colonel Gold, and his staff, set up its clearing and surgical station early on 19 December at a crossroads about 8 miles west of Bastogne. Gold, in consultation with the division supply officer, placed the station there, in what he expected would be the division service area, on the assumption that the 101st would be fighting as a part of a continuous front line. Around 1030 the company deployed its collecting elements,

32.For tactical developments, see Cole, Ardennes, ch. XIX.

33.101st Airborne Division After-Action Rpt, 17-27 Dec 44, box 14335, RG 407, NARA. Cole, Ardennes, pp. 480-81, provides figures on casualties in other organizations. His figures for the 101st Division differ from those in the report first cited, as do those given in Surg, 101st Airborne Division, Annual Rpt, 1944, pp. 12-13.

416

BASTOGNE, MAP 18

sending four or five ambulance jeeps and an evacuation officer to each of the four infantry regiments. The first patients arrived at about 1100. Late that afternoon the 32 6th Company commander, Major Barfield, left the crossroads with an ambulance convoy to take patients to the 107th Evacuation Hospital at Libin and to contact the 64th Medical Group about additional ambulances for the clearing station. On the return trip Barfield and his group found their road to Bastogne blocked by a blown bridge and columns of tanks and spent the night at the 107th.34

34.Surg, 101st Airborne Division Annual Rpt, 1944, pp. 9-10; 326th Airborne Medical Company After-Action Rpt, Belgium and France, 17-28 Dec 44, p. 3; G-3 Account of Bastogne Operation, in 101st Airborne Division Combat Intervs, box 24075, RG 407, NARA; Crandall Interv, 8 Jun 45, box 222, RG 112, NARA.

417

At around 2200 a German force of perhaps half a dozen armored vehicles and 100 troops, some dressed in civilian clothing, attacked the 326th Company clearing station. Evidently a reconnaissance element of one of the columns beginning to encircle Bastogne, it had come down a road from the northeast and caught the medical company totally by surprise. After a few minutes of sporadic automatic weapons fire, the Germans realized that they had run -into a medical installation. An enemy officer came forward and demanded the Americans' surrender. Colonel Gold, who had no alternative, complied, but a few officers and men on the west side of the company area ran off into the nearby woods. As the Germans were rounding up their prisoners, a truck column headed out of Bastogne to pick up supplies rolled unsuspectingly into the crossroads. Firing broke out again, from the Germans and from at least one of the trucks. The medics, caught in the crossfire, ducked for cover. Some were killed or wounded by stray bullets; a few managed to escape in the confusion. Soon the flames of burning American vehicles lighted the area. Americans and Germans alike made futile efforts to save the screaming wounded trapped inside the wrecks. The Germans withdrew toward the northeast, taking with them the remaining medical personnel and patients, as well as any equipment and supplies they decided not to destroy. The prisoners included Colonel Gold and his staff, an entire auxiliary surgical team, and 11 officers and 119 men of the 326th Company. With them, the 101st Airborne Division lost its hospital and its emergency surgical facility.35

Division headquarters learned of this misfortune shortly after midnight, from infantry patrols sent to investigate the shooting at the crossroads and from escapees of the 326th Company who made their way into Bastogne. The G-4 and the evacuation officers of the medical company in town, together with the regimental surgeons and Major Barfield, now acting division surgeon, quickly improvised a new evacuation system. They designated the regimental aid station of the 501st Parachute Infantry, centrally located within the city in a convent, as the collecting point for all division casualties. Meanwhile, the VIII Corps surgeon, at division request, deployed a collecting company and the clearing company of the corps medical battalion to move patients from Bastogne to evacuation hospitals. Some 170 men passed through this improvised evacuation chain on the twentieth. By 2330 on that day, however, the Germans had blocked the last road out of Bastogne. Completion of the encirclement left the VIII Corps collecting and clearing units outside the ring, along with Major Barfield, who had gone back to corps headquarters to report on the loss of the medical company and

35.101st Airborne Division After-Action Rpt, 17-27 Dec 44, box 14335, RG 407, NARA; Surg, 101st Airborne Division, Annual Rpt, 1944, pp. 10-11; 326th Airborne Medical Company After-Action Rpt, Belgium and France, 17-28 Dec 44, p. 4. For eyewitness stories, see Crandall Interv, 8 Jun 45, box 222, RG 112, NARA; Rapport and Northwood, Rendezvous with Destiny, pp. 467-68; Graves, Front Line Surgeons, p. 278; and Statement of Pfc E. E. Lucan, in 101st Airborne Division Combat Intervs, box 24075, RG 407, NARA.

418

bring forward additional supplies and equipment. Wounded soon began to accumulate in the regimental aid station; as early as 0630 on the twenty-first about 150 were on hand. 36

The 101st Division now was totally cut off from evacuation. Its medical officers, to give the steadily growing number of casualties at least essential life-saving treatment until American forces broke the German siege, improvised a hospital at the convent housing the regimental aid station. Maj. Martin S. Wisely, MC, regimental surgeon of the 327th Glider Infantry, headed a pickup staff made up of doctors and aidmen from the division antiaircraft, engineer, artillery, and tank destroyer units. To obtain more space and better protection from artillery and air attack for his patients, Wisely moved the hospital from the convent to the basement garage of a Belgian Army barracks. As the hospital population increased, he placed ambulatory patients in the barracks rifle range and used still another building for trenchfoot cases. Eventually, patients were distributed among basements all over the city, with the barracks garage reserved for the most severely wounded.

These facilities were, to say the least, primitive. The main garage ward, for instance, had no latrine and only a single electric light. A field kitchen set up at one end of the large room fed both staff and patients. The wounded “were laid in rows on sawdust covered with blankets. Each row had a shift of aidmen, and an attempt was made to segregate incoming cases into specified rows depending upon the seriousness of their wounds.” Those deemed unlikely to survive lay nearest the wall. “As they died they were carried out to another building where an impromptu Graves Registration Office was functioning.” Wisely and his assistants worked 24-hour shifts trying to keep their patients fed, reasonably warm, and in stable condition. They attempted no major surgery. According to the participants, morale among the casualties was “extremely high.” On Christmas Eve a ration of cognac and the voice of Bing Crosby singing “White Christmas” from a salvaged civilian radio provided some holiday atmosphere.37

Although the 101st Division hospital handled most of the casualties of the siege, it was not the only improvised medical facility in Bastogne. Combat Command B, 10th Armored Division, a Third Army unit that had entered the city from the south, improvised its own holding and treatment station after being cut off from its supporting armored medical company. On Christmas Eve the hospital took a direct hit from a German

36.Surg, VIII Corps, Annual Rpt, 1944, p. 8; Surg, 101st Airborne Division, Annual Rpt, 1944, p. 11; 326th Airborne Medical Company After-Action Rpt, Belgium and France, 17-28 Dec 44, pp. 3-5; G-3 Account of Bastogne Operation and Narrative, “Medical Evacuation and Supply,” both in 101st Airborne Division Combat Intervs, box 24075, RG 407, NARA; 169th Medical Battalion Annual Rpt, 1944, p. 12; 429th Collecting Company Annual Rpt, 1944, p. 3.

37.Quotations and most details from Rapport and Northwood, Rendezvous with Destiny, pp. 469-71. See also Surg, 101st Airborne Division, Annual Rpt, 1944, p. 11; 326th Airborne Medical Company After-Action Rpt, Belgium and France, 17-28 Dec 44, p. 5; 501st Parachute Infantry Draft After-Action Rpt, in 101st Airborne Division Combat Intervs, box 24075, RG 407, NARA. History of the 12th Evacuation Hospital, 25 August 1942 to 25 August 1943 (hereafter cited as 12th Evac Hist), pp. 111-12, contains additional eyewitness reports.

419

bomb. The resulting roof cave-in and fire killed a number of patients and also a Belgian woman nurse, who had volunteered to help tend the American wounded.38

Around the perimeter the infantry battalions set up their aid stations in the standard manner, with the main installations well sheltered in farmhouses or other structures and forward collecting elements close to the foxhole line. Short of litterbearers, the airborne units relied heavily on their ambulance jeeps to move their casualties. Where jeeps could not go, some units used toboggans, made of sheet metal torn off roofs, to slide wounded men across the snow. Jeeps of the division’s 326th Company carried patients from the battalion aid stations to the central hospital in Bastogne. One regimental surgeon, Maj. Douglas Davidson, MC, of the 502d Parachute Infantry, thought he could do as much for his wounded as the ill-equipped division facility; hence, he maintained his own holding hospital in the barn of the chateau housing the regimental command post. Davidson used horse stalls for wards and pressed the chaplains and a dentist into service as cooks. He estimated that “only about 5 men died of wounds who might have been saved had they been given medical care.” On Christmas Day, when German tanks and infantry broke through the main line of resistance and momentarily threatened the command post, Davidson routed out all of his wounded men who were able to walk, gave them all rifles, and led them to join a scratch force of headquarters personnel in repelling the attack.

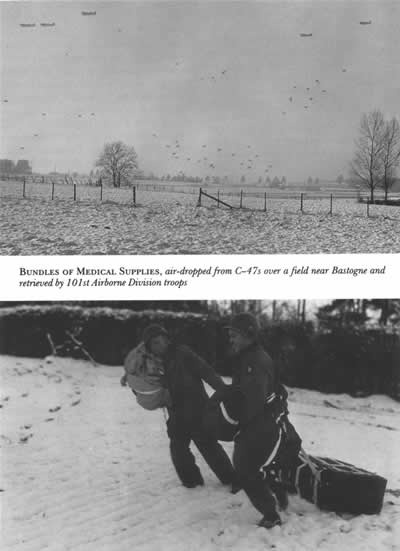

During this week of encirclement the hospitals in Bastogne faced two major problems: medical supply and the provision of emergency surgery. Of these the supply problem proved the easier to solve. A few tons of stores and a small issuing detachment of the 1st Medical Depot Company remained in Bastogne, and paratroopers also found an abandoned VIII Corps medical supply point. From these sources the surgeons obtained necessities for the first few days. Nevertheless, by the end of the third day of the siege, the hospitals were running short of penicillin, plasma, morphine, dressings, litters, and blankets. To keep patients warm in the unheated wards, the division collected the blankets of its dead and sent parties of men to salvage quilts and bed clothing from ruined dwellings. Food also was short, although the division reserved for the hospitals the limited available quantities of sugar, coffee, Ovaltine, and ten-in-one rations. The large-scale airdrop, which began on 23 December, alleviated most medical supply deficiencies. Penicillin and other medicines, plasma, Vaseline gauze, anesthetics, morphine, distilled water, syringes, sterilizers, litters, and blankets arrived in the parachuted bundles. The parachute cloth itself, and the wrapping of the bundles, went to the hospitals to provide addi-

38.Surg, 10th Armored Division, Annual Rpt, 1944, p. 15; 101st Airborne Division After-Action Rpt, 17-27 Dec 44, box 14335, RG 407, NARA; Rapport and Northwood, Rendezvous with Destiny, pp. 471 and 546.

39.Rapport and Northwood, Rendezvous with Destiny, pp. 470-71. For Davidson, see S. L. A. Marshall, “Bastogne,” pp. 197-98, and Narrative (source of quotation), 592d Parachute Infantry, both in 101st Airborne Division Combat Intervs, respectively box 24074 and box 24075, RG 407, NARA.

420

tional warm covering for patients. Whole blood also was among the air-delivered supplies, but the bottles broke on landing or were destroyed when a German shell blew up the room where they were stored.40

As the days of encirclement went by, the division surgeons realized that the number of wounded awaiting treatment was increasing and that they were going to die unless they underwent major operations immediately. Equipment for such surgery was at hand: the operating theater outfit of the 42d Field Hospital platoon that had withdrawn from Wiltz. However, the few surgeons in Bastogne either could not be spared from other tasks or lacked the qualifications to perform the work required. Seeking a way out of this dilemma, Major Wisely on 26 December obtained authority from the division to try to negotiate the passage of the most severely wounded through German lines. Wisely, assisted by a captured German medical officer, made contact with the enemy commander opposite the southwest sector of the perimeter. The German responded favorably to the evacuation proposal but postponed a final answer until the next day. By that time Third Army troops had ended the siege.41

Even as Wisely was trying to arrange for the wounded to come out of Bastogne. Third Army efforts to send surgeons in bore fruit. The army surgeon's office obtained six medical officers and four enlisted technicians, all volunteers, from the 4th Auxiliary Surgical Group and the 12th Evacuation Hospital to go into Bastogne and set up an emergency surgical facility. The army at first intended to drop these men into the perimeter by parachute; but, to their relief, they were able to travel by less hazardous means. One officer was flown in on Christmas Day in a light plane and the rest followed by glider during the afternoon of the twenty-sixth.

When the main body of the surgical group walked into the garage hospital, about 150 patients, all severe cases, remained, the rest having been moved elsewhere. The need for the reinforcements’ services was all to apparent, as “the odor of gas gangrene permeated the room.” Using the 42d Field Hospital equipment, which included an operating lamp and an autoclave, the surgeons and technicians set up a four-table theater in a small tool room adjoining the garage. They examined and sorted the patients and by nightfall had the first men on the tables. The volunteers, assisted by three Belgian women and by a 10th Armored Division battalion surgeon who was a qualified anesthetist, operated all through the night and until around noon of the twenty-seventh, trying to repair wounds that had gone from two to as many as

40.Surg, First U.S. Army, Annual Rpt, 1944, p. 22; Surg, Third U.S. Army, Annual Rpt, 1944, p. 171; Surg, 101st Airborne Division, Annual Rpt, 1944, pp. 11-12; Rapport and Northwood, Rendezvous with Destiny, pp. 469-71; Narrative, “Medical Evacuation and Supply,” and Interv, ACofS, G-4, and Others, both in 101st Airborne Division Combat Intervs, box 24075, RG 407, NARA; 101st Airborne Division After-Action Rpt, 17-27 Dec 44, box 14335, RG 407, NARA.

41.Rapport and Northwood, Rendezvous with Destiny, p. 471; Narrative, “Medical Evacuation and Supply,” and 327th Glider Infantry Journal, 26 Dec 44, both in 101st Airborne Division Combat Intervs, box 24075, RG 407, NARA. The Third Army's chief of staff had plans for moving surgeons into Bastogne under a white flag. See Cole, Ardennes, p. 609.

421

BUNDLES OF MEDICAL SUPPLIES, air-dropped from C-4 7s over afield near Bastogne and retrieved by 101st Airborne Division troops

422

eight days without surgical attention. Of necessity, they performed many amputations. Evacuation of casualties from Bastogne began on the twenty-seventh, but the surgeons, after a rest around midday, operated for another twenty or so hours. Even after a near-miss by a German bomb blew in the operating room door and brought down part of the ceiling, they kept on, working for a time by flashlight. The volunteer group, every member of which—both officer and enlisted— received the Silver Star, completed about fifty major operations, with three postoperative deaths.42