ANNUAL REPORT

OF

MEDICAL DEPARTMENT ACTIVITIES

1944

DIVISION SURGEON

1ST U.S. INFANTRY DIVISION

APO 1, U.S. ARMY

INDEX

PRE-INVASION PERIOD, 1 JANUARY 1944 TO 6 JUNE 1944 1

REORGANIZATION AND REEQUIPMENT 2

SANITATION AND HEALTH 4

INVASION AND NORMANDY CAMPAIGN, 6 JUNE 1944 TO 19 JULY 1944 7

EVACUATION 8

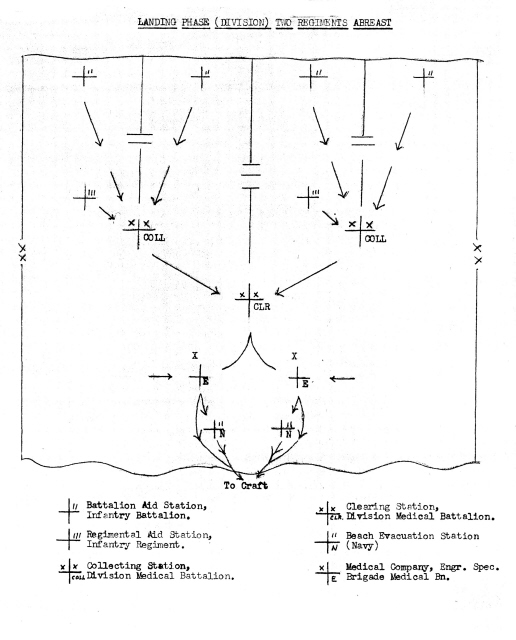

Landing Phase (Diagrammatic) 8a

SUPPLY 10

PERSONNEL 10

SANITATION AND HEALTH 10

EVACUATION 13

Letter of Division Surgeon, SUBJECT: Evacuation of Patients 14a

SUPPLY 15

SANITATION AND HEALTH 16

BATTLE OF GERMANY, 12 SEPTEMBER 1944 TO 31 DECEMBER 1944 18

EVACUATION 21

SUPPLY 24

PERSONNEL 24

SANITATION AND HEALTH 25

Letter of Division Surgeon, SUBJECT: Trench Foot 29a

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 31

ANNEXES:

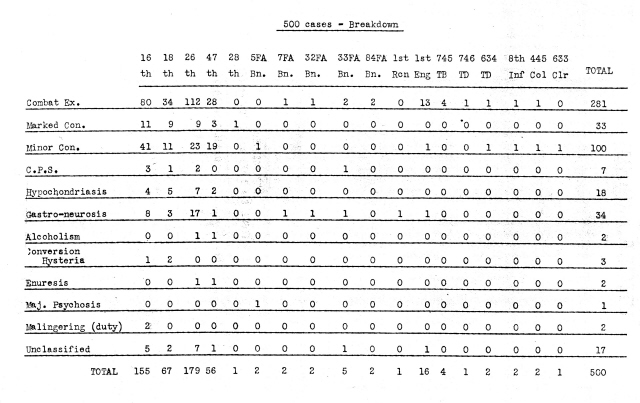

Annual Report: - Division Psychiatrist.

Annual Report: - Division Dental Surgeon.

In compliance with AR 40-1005 and letter AG 319.1 (9-15-42) EG-M, War Department, 22 September 1942, Subject: `Annual Reports, Medical Department Activities`, the following report is hereby submitted. This report covers the period 1 January 1944 to 31 December 1944. It will cover the pre-invasion period, D-Day landings on the continent, and the subsequent campaigns in France, Belgium and Germany.

On 1 January, 1944 the division was located in the Southern Base Section, England, with the units widely dispersed in the vicinity of Axminster, Swanage and Blandford. The division arrived in this area 8 November 1943 from Sicily and entered upon a period of reorganization and training for future combat, which was proven by later events to be the invasion of the continent.

Combat teams were kept intact but medical service for this situation was not normal. Unit dispensaries were maintained in all areas and evacuation was direct to nearby Station and General Hospitals. Organic medical transportation of the division (3/4 ton ambulances) were used for the evacuation of patients from division units to hospitals.

In general, medical supplies and equipment were adequate and easily obtained from medical supply depots located in the Southern Base Section.

PRE-INVASION PERIOD, 1 JANUARY 1944 TO 5 JUNE 1944

Training in the medical service of the division was easily converted from technical to tactical subjects and primarily interpreted in terms of preparation for combat. The majority of the medical personnel at this time were considered as `well trained` because they had undergone some combat duty and had taken part in the intensive training program which had been, completed in Sicily following the Sicilian campaign. A great part of the early technical training consisted of chemical warfare subjects (identification of gas and treatment of gas casualties). In connection with this training, all men in the division were put through the `Gas Chamber`. Many of the medical department enlisted personnel were given the opportunity to attend schools for Sanitary Technicians and Medical and Surgical Technicians. Several Medical Officers who had come to the division following the Sicilian campaign were given the opportunity to attend the Medical Field Service School at Shrivenham. Those officers who had had combat experience were given the opportunity to attend certain professional schools such as School in Plaster Cast Technique, School in Maxillo-facial Surgery, and School in Neuro-psychiatry. In connection with this latter school and with the change in T/O dated July 1943 assigning a division psychiatrist, one Medical Officer of the division was trained for this duty at this school. (See report of Division Psychiatrist). As the training progressed more emphasis gradually was given to hardening exercises and exercises designed to prepare men for amphibious operations. Road marches, supervised athletic programs, and cross-country litter-bearing were participated in by all medical units of the command. `Speed marches` designed to enable each soldier to complete four (4) miles in forty-five (45) minutes, five (5) miles in one (1) hour, nine (9) miles in two (2) hours and sixteen (16) miles in four (4) hours were instituted.

2

These hardening exercises were completed with a twenty-five (25) mile road march in eight (8) hours. Not only the enlisted personnel but also the officer personnel of the division participated in this type of training.

The first amphibious exercise to be held, putting into practice the above program, took place on approximately 8 February 1944 and involved the medical service of one combat team. This exercise took place at the United States Assault Training Centre (USATC) at Woolacombe, Somerset, England. Those medical units which remained behind in their bivouac areas concerned themselves with amphibious operations using local terrain as simulated beaches. At the completion of the exercise at the USATC critiques were held to correct any errors or deficiencies which had appeared during the exercise. Further instruction was carried out in teaching the men the newer phases of casualty handling and evacuation as presented by the instructors at the USATC. Newer and more specialized equipment which had been used at the USATC was discussed and demonstrated to the key medical personnel of the division. This demonstration included ships-to-shore evacuation by means of `DUKWs` and the transportation of medical supplies from landing craft to beach by means of waterproofed 80 mm. mortar shell cases.

Intensive training along the above lines continued up until the 25 April 1944 when the so called Fabius exercise began. This also involved a practice amphibious operation on the southern coast of England. The entire division medical service participated and the problem was based on the `Neptune` plan which was name given to the actual invasion of the continent on 6 June 1944. Following the completion of this exercise the units returned to their bivouac areas and again the deficiencies which showed up in the exercise were corrected. The period following this exercise was devoted to putting the finishing touches in preparation for the `Neptune` operation. Starting 15 May 1944, the various units of the division began their departure to their respective marshaling areas on the southern coast of England; they were divided into the assault and the follow-up elements. While in the marshaling areas, small unit training continued with special reference to first-aid in combat. The use of the parachute pack, seasick pills and halazone tablets which were supplied to each soldier in the marshaling area was taught. This completed the final phase of training and planning for the invasion of the continent.

REORGANIZATION AND REEQUIPMENT:

The major changes in the T/O at this time (T/O & T/E dated 9 July 1943) consisted in the establishment of a Special Troops Medical Detachment and the appointment of a Medical Officer as a Division Psychiatrist. Changes among the Medical personnel consisted mainly in a reduction within the Regimental Medical Detachment and Medical Battalion. In view of this fact few new replacements were received and therefore the division medical service was fortunate in having a majority of its personnel well trained and with previous combat experience. Immediately prior to the D-day landing, the division was authorized a fifteen percent (15%) increase in Medical Department personnel over and above the T/O. This was to insure adequate and immediate replacement for the casualties expected to occur on and immediately subsequent

3

to D-day.

Under the new T/ (T/O & T/E dated 9 July 1943) the following changes of equipment took place.

1. Thirty (30) ambulances (3/4 ton, field) were authorized for the division on basis of ten (10) per Collecting Company. This represented a reduction of twelve (12) ambulances from previous T/E and it was anticipated that to make up for the decrease other organic transportation of medical units would have to be used for motor evacuation. From past experience it had been learned that 1/4 ton truck, 4 X 4, (`jeep`) lent itself to evacuation for walking and litter patients. Following a detailed study, litter racks were constructed for these vehicles in the Battalion Medical Sections and in the Collecting Companies. These racks allowed the transportation of three litter patients, two (2) over the hood and one (1) across the rear axle. They were constructed permanently to the jeep in such a way as not to interfere with, it being used for other purposes. The only demonstrable disadvantage was that litter patients were `carried` crosswise therefore extending beyond the natural width of the vehicle. However, in actual practice this disadvantage could easily be overcome by careful drivers and therefore this plan was adopted throughout the division. The D-day landings and subsequent combat have proven that these so-called `Jeep` ambulances are practicable and have a definite advantage in motor evacuation of litter patients.

2. Unit Medical Equipment Packs were received.

3. One (1) Otoscope, one (1) Ophthalmoscope, and one (1) Sphygmomanometer were authorized for each Regimental and Battalion Medical Section, each Separate Battalion Medical Section, each Collecting Company and each Clearing platoon (Total: 24 of each).

4. Two additional medical chests were added to the Clearing Company namely Chest, laboratory, field, and Chest, plasma.

5. Although previous T/E had authorized Gas Casualty Chests and Sets, the division received these items for the first time.

It was felt that certain articles on the new T/E and which had never been used by the Clearing Company in previous campaigns were of no value. Authorization was requested and granted to turn these items in, namely Carrier, field, collapsible (`wheeled litter`) and Kits, medical, private.

Certain supplies over and above authorized T/E and equipment were issued specifically for the D-day operation as follows:

(1) Each Battalion Medical Section

|

Litters |

12 |

|

Blanket Set, small |

2 |

|

Splint Set |

1 |

|

Water-proofed shell cases containing morphine syrettes, sulfanilamide crystals, plasma, dressings, and bandages. |

|

4

(2) Each Collecting Company

|

Splint Set |

2 |

|

Water-proofed shell cases (for contents see above) |

16 |

(3) Clearing Company

|

Splint Set |

6 |

|

Blankets |

600 |

|

Litters |

200 |

In connection with the emphasis placed upon Chemical Warfare, gas mask spectacles (inserts) were provided and fitted for two hundred thirty-seven (237) enlisted men and officers of the division.

Prior to embarkation each soldier was issued at the marshaling area the following items: One (1) parachute pack, halazone tablets, and sea sickness pills. No critical shortages of T/E or equipment and supplies authorized in excess of T/E existed prior to embarkation.

SANITATION AND HEALTH:

The division experienced during the greater part of the period a cold climate with moderate rainfall. For the most part the majority of troops were housed in military barracks, public buildings, Nissen Huts, and winterized tents. On the whole the quarters for the enlisted personnel were `cramped` and the basic minimum floor-space allotted for each man was reduced to thirty-five (35) sq. ft. per man by direction from the Office of the Chief Surgeon, ETOUSA. The climate plus the relative overcrowding in the soldiers` quarters had a direct effect on the health of the command in the incidence of respiratory diseases. Insects during the period were non-existent and therefore no problem.

Water Supply:

Water supply was adequate for all purposes (washing, bathing and drinking) and was obtained from local municipal sources. All drinking sources were required to have a bacteriological examination and those sources found to be non-potable were chlorinated by the division engineer water units. Certain non-potable sources were corrected by British engineers by the installation of new piping.

Waste Disposal:

Latrine facilities throughout the command were of two types, bucket type and flush toilets. No difficulties were experienced with the latter type other than the usual repairs and cleaning out of septic tanks. The bucket type latrine however, was consistently unsatisfactory. The emptying of the latrine buckets was the responsibility of local civilian contractors who were supposed to make at least one (1) daily collection and in some instances where the number of buckets were inadequate, as many collections as were necessary to prevent the buckets from overflowing. Very few of these civilian contractors handled the collection properly. In many instances, the buckets were not collected as often as required and consequently there was spillage and pollution around the latrines. Other contractors collected the buckets often enough but failed to clean the buckets and disinfect them chemically as was required by contract. In other instances the

5

human waste had to be disposed of by the respective units and this was done by burial. The major criticisms were therefore:

1. Too few buckets allotted to the troops (5%).

2. The failure of the `Collection system`.

3. The pollution of the latrine area during the emptying of the buckets.

All kitchen wastes were sorted out according to existing directives, kept in covered metal containers, and then hauled away by local civilian contractors in much the same way as human wastes. The same deficiencies existed in this system as existed in the collection of bucket latrines. Cans were allowed to overflow because of failure to collect them regularly; pollution and spillage around the kitchen area resulted from improper handling of the cans; and in many instances cans were returned by contractors unclean and leaking.

Messes:

Because of the shortage of kitchen facilities battalion kitchens were the rule. These kitchens were British in character and generally failed to measure up to American military standards. First of all storage space for perishables and non-perishables was inadequate and poorly ventilated. In an effort to conserve the field ranges (stoves), the British coal stoves were used. The use of coal in the kitchens resulted heavy smoke and coal soot. All the kitchens showed evidence of being used prior to arrival of the division. Therefore, the general cleanliness of kitchens was a major problem. In spite of these disadvantages kitchen sanitation was maintained at relatively high level.

Food:

Type `A` ration was issued for practically the entire period prior to embarkation excepting in tactical exercises when emergency rations were used (`B`, `D`, & `K`). In all respects the ration issue was satisfactory in quality and quantity; mess personnel were competent and the majority of cooks had previously attended Cooks and Bakers School. Because of this food was well prepared and wastage was rare. Although no refrigeration facilities existed, meats were received in frozen condition and immediately consumed. At no time during the pre-invasion period was it thought that vitamin supplements were necessary. A quartermaster bakery unit was attached to the division during this time and it supplied the division with fresh bread daily.

There was only one instance where poor mess management and sanitation affected the command. Just shortly prior to embarkation and while one battalion of an infantry regiment was in the marshaling area, about 30% of the command suddenly developed an afebrile diarrhea. This marshaling area was commanded and operated by an SOS unit from Southern Base Section. A careful investigation revealed that all the cases of diarrhea were messing at one kitchen and that this kitchen failed to provide adequate mess-kit washing facilities for the number of personnel that it fed. An immediate correction of this deficiency resulted in a clearing up of the situation and no new cases of diarrhea were reported thereafter. None of the men effected with the diarrhea were lost to the command for the D-day landings.

6

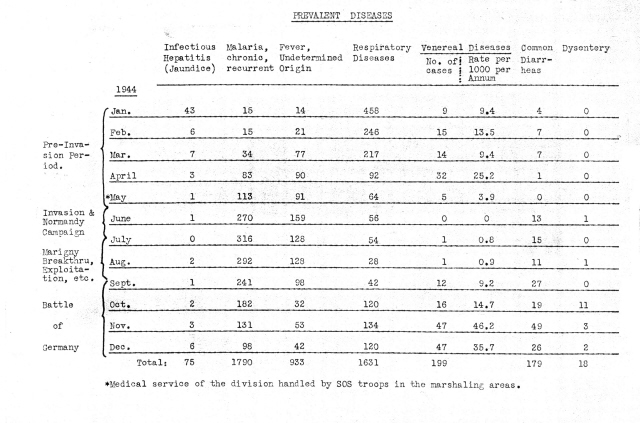

DISEASES:

Infectious Hepatitis (Jaundice): In retrospect, cases of infectious hepatitis had started in the fall of 1943 while the division was in Sicily. The incidence of this disease increased and continued even after the arrival of the division in the United Kingdom. However, there was a gradual decline in the rate beginning with the month of January 1944 at which time there were forty-three (43) cases as compared to one hundred forty-four (144) for the month of December 1943. The month of February 1944 showed only six (6) cases of Infectious Hepatitis and from that time on only sporadic cases occurred throughout the command.

Respiratory Diseases: The start of the year in the United Kingdom was characterized by the large number of respiratory diseases of all types and although there were four hundred fifty-eight (458) cases reported in January 1944 as compared with six hundred twenty-eight (628) cases in December 1943 this still represented a high rate. It is believed that the causes of the high incidence of these diseases were (1). the change of climate from a more or less sub-tropical climate to a north temperate) (2). the overcrowding of troops in billets and (3). the poor heating and ventilation, facilities in the billets.

All possible measures were taken to prevent the spread of these diseases. Head-to-foot sleeping was put into effect in all sleeping quarters. When practical, shelter halves were used to make sleeping cubicles. Proper ventilation, especially during sleeping hours was effected and supervised by the Charge of Quarters in unit billets. Cases of respiratory diseases that were kept on a `Quarters` status were isolated and cared for at unit dispensaries. All food handlers received a daily health inspection before reporting for duty and if any were found suffering from a `cold`, they were immediately sent to sick call for treatment and disposition.

Under this strict control, respiratory diseases gradually declined and at the end of May 1944 prior to the invasion of the continent, the number of respiratory diseases had declined to less than fifty (50) cases monthly.

Malaria: In the early part of the pre-invasion period, Malaria which had been a problem in Sicily and in the first several weeks in the United Kingdom appeared to have died out. However, an increase in Malaria throughout the division occurred in the latter part of March and from that point on continued to increase. Likewise there was a notable increase in Fever of Undetermined Origin (FUO), many of which were later diagnosed in hospitals as Malaria. These cases were obviously Malaria, chronic, recurrent because of the absence of the malaria-bearing mosquito in the United Kingdom. Furthermore, many of these cases were of the so called `Latent Type` occurring in those individuals who had taken atabrine and quinine prophylaxis and who had had no attacks of Malaria or FUO prior to this time. Because of the increase of Malaria suppressive atabrine therapy was instituted for all personnel having a past history of Malaria (Ltr. Hq, First US Army dated 21 May 1944). This disease resulted in the loss of a substantial number of military personnel just prior to the embarkation and landing on the continent.

7

Communicable Diseases: For the most part communicable diseases consisted of sporadic cases of Meningitis (Cerebro-spinal), Mumps, and Measles. None of these diseases became epidemic and were easily handled by so called `working` quarantine. All immunizations against Typhus Fever, Typhoid Fever, Tetanus and Small Pox were completed prior to D-day.

Venereal Diseases: Excepting for the month of May 1944 when there were thirty-two (32) cases of venereal disease (rate/1000/annum - 25.2 ) these diseases were no problem. In general the monthly rate/1000/annum averaged about ten (10). However, because of the fact that venereal diseases were quite prevalent in the United Kingdom, measures were being taken all the time to keep these diseases under control and at a minimum. Personnel going on pass or furlough were informed of the location of "pro-stations" available to them; individual `pro-packets` were issued to all personnel desiring such; sex hygiene lectures were given periodically: sex hygiene films were shown as part of the training program. It is believed that the marked increase in venereal diseases that occurred in the month of April tended to bear out past experience in the division when combat is imminent, troops become lax in their venereal discipline and tend to assume a fatalistic attitude toward the future. Moreover, as the invasion of the continent became more imminent, troops were restricted to the so-called `banned areas` and an influx of professional prostitutes into these areas was noticed. The month of May 1944 showed only five (5) cases of venereal disease but this low rate is explained by the fact that the division was in a marshaling area and restricted from contact with civilian or other military personnel.

INVASION AND NORMANDY CAMPAIGN, 6 JUNE 1944 TO 19 JULY 1944

On 6 June1944, the 1st US Infantry Division and attached landed on the continent (Normandy). A heavy naval and air bombardment preceded the assault on the beach which was carried out by one combat team of the division and by one combat team of the 29th Division attached. The naval bombardment had failed to knock out several enemy concrete emplacements which were situated and built in such a manner as to resist all heavy gun fire except a direct hit. In addition unfavorable weather had reduced the effectiveness of certain `secret` support weapons. The fire directed against the assaulting troops was so intense as to prevent a penetration of these emplacements until anti-tank weapons could be landed. H-hour had been 0630 and it was not until 1000 hrs that the enemy positions on the cliff overlooking the beach were destroyed or captured. Although the enemy continued to resist fiercely, the assault troops and supporting troops were finally able to secure the small key village of Colleville-Sur-Mer. By the 9th June 1944 the hard shell of enemy resistance had been broken. Although the enemy began to dig in, set up road blocks, erect wire entanglements, and sow numerous mine fields, he was unable to prevent the division`s advance to Caumont. Throughout the entire period enemy air activity was negligible except for single enemy bomber attacks occurring after dark. The division remained in a defensive position at Caumont until the 15th July 1944 when it was relieved by the 5th U. S. Infantry Division.

8

EVACUATION:

The medical plan for D-day had anticipated the following evacuation plan:

1. The Company Aid men to go ashore with their respective companies to tag the wounded, render first aid, and if possible mark the location of the casualties

2. The Battalion Aid Station Sections to follow with certain equipment and twelve (12) litter bearers, and support the assaulting battalions. They would render further medical treatment and attempt to group casualties to collecting points for later evacuation to the beach.

3. The Naval Medical Sections (Shore Party) to land approximately at the same time as the Battalion Aid Stations, establish a Beach Evacuation Station, receive casualties from the beach, administer first-aid, and effect seaward evacuation.

4. The Collecting Companies to land next at a time when the attack had moved off the beach; the litter bearer platoons to land first to aid the evacuation of the Battalion Aid Stations. The Collecting Station Platoon to follow, proceed to a station site and receive all casualties from the front. The Ambulance Section to land next.

5. Soon after the landing of the Collecting Company, Medical of the Engineer Special Brigade to cone ashore with its equipment and personnel intact, and perform the following services: (a). Receive casualties from Collecting Stations. (b). Provide treatment for non-transportables thru its attached surgical teams, and the treatment and seaward evacuation of transportable casualties. To cooperate with the Shore Party in loading all craft used for ship-to-shore evacuation. (c). To operate a medical supply dump. The Naval Beach Evacuation Station and the Medical Company of the Engineer Special Brigade to remain in the beach area regardless of the movements of the Army Medical units. The Medical Company of the Engineer Special Brigade at this phase of the operation to substitute for the Division Clearing Station.

6. The Division Clearing Station to land as soon after the Medical Company depending upon the forward progress of the infantry. Once this had landed and set up, medical service of the division became normal.

7. The rear evacuation was to be kept under control of higher headquarters which was to make the following medical facilities available:

Field Hospitals

Evacuation Hospitals

Ambulance Companies

Collecting Companies

Clearing Companies

Supply Depots

Auxiliary Surgical Groups

Diagramatically this evacuation plan is represented as follows:

8a

9

In spite of the pre-invasion planning and exercises, the medical service and evacuation on D-day until D plus 3 was quite confused. Many of the beach medical units and also medical units of the division were not put ashore according to plan and others were landed by mistake on wrong beaches. Likewise the tactical situation failed to progress as anticipated and this served to alter the landing tables of the medical units. Many of the medical units of the division and of the amphibious medical battalion were unable to bring their supplies and equipment ashore, which were lost in the sea or damaged by enemy activity. Within the division medical service then first-aid to the wounded was provided by the Company aid men who had come ashore with the assault infantry companies. Litter bearers from the Battalion Sections and Collecting Companies followed close behind and collected the casualties and prepared them for their evacuation.

Casualties were evacuated from shore-to-ship by whatever means available (assault boats, DUKWs, and any other available craft). Priority was given to non-transportables. Of necessity many of the casualties remained on the beach under care of the Division Clearing Company personnel and of medical personnel from other units. Although one platoon of the Division Clearing Company came ashore at 1730 hrs on D-day and the second platoon joined it at 2130 hrs, neither of the platoons failed to function on this day. The entire company personnel assisted in clearing the beach of casualties and thereby functioning as an emergency collecting unit. On D plus l at 0630 hrs, the Division Clearing Station was established and opened on the bluffs just east of Vierville-Sur-Mer. From this time on division medical service was normal, namely from Battalion Aid Stations through Clearing Station. Furthermore, there were no facilities on the beach for handling non-transportable casualties or other seriously wounded patients. To effect this evacuation and treatment, the following plan was put into effect. Two of the auxiliary surgical teams, which were ashore at this time but which were unable to operate because they lacked equipment, were secured and set up at the Division Clearing Station, using the Division Clearing Station surgical instruments, supplies, tentage, etc. They proceeded to care for the wounded and continued to do so until D plus 3 at which time they were able to join their parent unit. To prevent the casualties from piling up at the Clearing Station and to facilitate the evacuation to shore and to ship, Clearing Station personnel were used as litter bearers to carry litter patients to the shore where the amphibious medical battalion had set up small collecting points. Walking wounded were likewise directed to the same shore points and in some cases were drafted as additional litter bearers. The litter haul from the Clearing Station site was approximately one thousand (1000) yards down the bluff and over rather difficult terrain. To supplement the litter bearers, twenty-four (24) German prisoners were obtained from a nearby prison cage. The shore collecting points at this stage took over the responsibilities of getting casualties to the ships; DUKWs were brought to the Clearing Station, loaded up with litter patients and dispatched directly to the ships. The evacuation of the Clearing Station from D-day to D plus 3 remained under division control, after which it passed into the hands of the amphibious medical battalion which had meanwhile been able to locate its equipment and set up.

After D plus 3, the tactical progress of the division was rapid, moving in the direction of Caumont and arriving in that vicinity on June 12, 1944. From D plus 3 on evacuation was normal and the Division Clearing Station was evacuated by First Army Collecting Companies.

10

After a few days in the vicinity of Caumont when it became apparent that the division was to occupy a defensive position, the Clearing Station expanded to its full capacity and instituted the policy of holding minor casualties and diseases which could be returned to duty within five (5) days. Soon after the arrival at Caumont, a Field Hospital Platoon was set up close to the Clearing Station and in support of the division. Their primary function was to handle non-transportable casualties. In this situation evacuation in the division was rapid due to the proximity of the Collecting Stations, (within five (5) miles) and also because of the good road network. It was in this position that the Clearing Station came under enemy artillery fire for the first time. Apparently the enemy fire was directed at artillery located in the vicinity of the Clearing Station. Late in the afternoon of July 9, direct hits were recorded, causing no casualties. Some damage to vehicles resulted. On the 15th July, the entire division was relieved at Caumont by the 5th U. S. Infantry Division and moved to the vicinity of Columbiers. Here, it reorganized and reequipped, completing this on19 July 1944. One platoon of the 47th Field Hospital which was in support of the division moved to this site also but did not operate. Evacuation during this short period was normal.

SUPPLY:

Although the plans for supply did not work as intended, still sufficient supplies were available from D-day to D plus 3 at which time the Division Medical Supply Section set up and took over the normal supply of the division. From D-day to D plus 4, items which were intended for the advance section of the First Army Medical Dump were unloaded on the beach and in the vicinity of the Division Clearing Station. In addition the Navy had unloaded on the beach extra supplies consisting of dressings, plasma, litters, blankets, and splints. The expendable supplies were in water proofed rubber bags. These were immediately available to the functioning medical units. The supply within the division medical service was at no time critical in spite of the large number of casualties. There were very few losses of non-expendable items and the expendable supplies which had been taken ashore with the division medical units were adequate. The Division medical Supply Section came ashore on D plus 3, and was set up and functioning on D plus 4. From this point on all requisitions for medical supplies were filled from the Division Medical Supply Section which in turn submitted its requisition through channels to Army Medical Supply Depots.

PERSONNEL:

No changes in T/O occurred at this time. For the first time since being overseas and in combat the division suffered two (2) fatal casualties among Medical Department Officers due to enemy action. Both of these were Captains, MC, and both were Battalion Surgeons. The first one was seriously wounded on D-day and subsequently died in a hospital in the United Kingdom; the second was killed by a mortar shell in the Caumont area.

SANITATION AND HEALTH:

The period covered by this part of the report was characterized by moderate to heavy rainfall. So far as the tactical situation permitted, troops were housed in public buildings and civilian establishments. Toward the latter part of the period, flies began to appear in large numbers. Fly control measures were instituted at this time which consisted primarily of spraying latrines and kitchen areas with weak solution of creosol. Spraying was accomplished by

11

using a three (3) gallon as decontaminating pump. The kitchen trucks which had been screened in and fly-proofed prior to the invasion were now used. Unit surgeons made frequent sanitary inspections to assure themselves that fly control measures were adequate and as a result of this no increase in fly-borne diseases resulted.

Also in the latter part of this period, there was a noticeable increase of mosquitoes in the division area. Because of the high incidence of Malaria the proper identification of these mosquitoes was important. Several specimens were thereupon captured and taken to the 10th General Medical Laboratory, where they were identified as a variety of Culex.

Water Supply:

All water used for drinking and cooking was chlorinated according to Army regulations by division engineer water units. Primary sources of water supply were the streams within the division area.

Waste Disposal:

Latrine facilities were primarily straddle trenches and `cat holes`. When buildings were used, some flush toilets were available. All kitchen wastes were disposed of by either burial or incineration. Trash, rubbish, and cans were likewise disposed of by incineration. In some of the local town areas trash dumps were established.

Messes:

Kitchen trucks were used in the preparation and cooking of food. For the most part these kitchens were kept together either in the Battalion or Regimental Field Train along with the other service elements of the combat unit.

Food:

During the early part of this period the ration was of the Field Type (`C`, `D`, `K`, `5-in-1`, and `10-in-1`). The menus from those rations were not sufficiently varied but were satisfactory as to quality and quantity. Small gasoline stoves (single-burner type) were part of the equipment of each squad of a rifle company. These stoves enabled the men to prepare hot meals for themselves when the tactical situation prevented hot meals from the company kitchens being served to them. As the campaigns got under way the `B` ration came into use and the emergency rations were consumed only when the tactical situation required. Fresh meats were received in frozen condition and consumed immediately. Some of the units supplemented their messes by local purchases of eggs and certain types of vegetables and fruits; local purchases of milk, butter, cheese, and other dairy products were prohibited.

Diseases:

Malaria: Malaria, and FUO`s continued to show an increase from the day of the landings and were the major disease problems of the command. During

12

the month of June, two hundred sixty (260) cases of Malaria and one hundred sixty-three (163) cases of FUO`s were reported; during the month of July three hundred sixteen (316) cases of Malaria and one hundred twenty-eight (128) cases of FUO`s occurred. At no time was there evidence to show that these cases of malaria were other than chronic, which had been initially incurred in the Mediterranean Theatre. All efforts were made to control incidence of the disease by use of atabrine prophylaxis which was being given to all personnel who had been in the Mediterranean Theatre.

Venereal Disease: During this campaign, venereal diseases were no problem. No cases were reported for the month of June and only one (1) new case was reported for the month of July. All towns in the division area were placed `Off Limits` to all division personnel. This was enforced by military police. Consequently, social contact between military personnel and civilian population was kept at a minimum.

Communicable Diseases: Communicable diseases were of no consequence during the defensive period in the vicinity of Caumont. Immunizations were brought up to date according to existing directives from higher headquarters.

MARIGNY BREAKTHROUGH, EXPLOITATION, AND THE CAMPAIGN OF NORTHERN FRANCE AND BELGIUM, 20 JULY 1944 TO 11 SEPTEMBER 1944:

The plan for the Marigny breakthrough called for sudden penetration in the enemy lines; by several US divisions, including the 1st US Infantry Division. This breakthrough was to. Be preceded by a heavy aerial bombardment during which six thousand (6000) tons of bombs were to be dropped on the enemy.

The initial drive was south toward Marigny and then toward Coutances. By 31 July 1944, Coutances had been seized and the division had advanced south of the town to regroup for exploitation of the operation. On 1 August 1944 the division had started driving toward Mortain in order to create a corridor thru which allied armour could pass to attack the Brittany Peninsula. Shortly after midnight on 1 August 1944 the enemy attacked the division with elements of his air force. Numerous anti-personnel bombs were dropped in unit CP`s and the division CP, which at that time was located about three hundred (300) yards from the bivouac area of the Clearing Station and the supporting Field Hospital. Over two hundred (200) casualties occurred from this raid.

The division continued to move rapidly will light enemy resistance until it reached the vicinity of Mortain, where the enemy put up stubborn resistance. This sector was shortly thereafter turned over to a combat team of another division thus allowing the division to extend its zone of operation south of Mortain to the vicinity of Mayenne. The division remained in the vicinity of Mayenne until 13 August 1944 when it began an attack north and west toward Le Ferte-Mace. By 17 August 1944, the division had penetrated the Foret D`Andaine and secured its objective. Its position here served to aid in closing the Falaise-Argentan pocket which had been created by an encircling movement of British and American troops. However during the following six (6) days, there was little enemy contact.

13

On 24 August 1944, the division began its move across France into Belgium. The first move took the division to the vicinity of Chartres; enemy opposition was practically nil. On 27 August 1944, the division crossed the Seine River just south of Paris, still meeting very little opposition, and still continuing to advance rapidly with few casualties. By 30 August 1944 the division had advanced through Chateau Thierry, Soissons, and Laon. These movements constituted the pursuit of a fleeing and disorganized enemy.

By 2 September 1944 the division had arrived in the vicinity of Maubeuge south of Mons in the vicinity of the Franco-Belgian border. Meanwhile at the same time the 3rd Armoured Division which was operating on the right flank of the division had penetrated into Belgium east of Mons thereby cutting off the escape route of approximately five (5) German divisions. This tactical situation there upon produced one of the most costly single defeats suffered by the German army in the entire campaign and at the same time also created some of the most serious problems of evacuation and supply for the division medical service. This battle became known as `The Mons Pocket` which was fought from the 2nd to 6th September 1944. When the final reports of the disaster could be correlated and a reasonably accurate total made, it was found that over seventeen thousand (17,000) German prisoners had been taken and at least two thousand (2,000) Germans had been killed. One thousand seventy-nine (1079) enemy wounded had been cleared through the Clearing Station. It was evident that the total of five (5) German divisions had been almost completely destroyed. During the 6th and 7th September 1944, the division moved rapidly east from Mons to seize the city of Namur, Huy, and eventually Liege, all cities on the Meuse River. Opposition was light up to this point but as the combat columns of the division proceeded towards the German border enemy opposition began to stiffen and the Germans began to prepare strong defenses. However, enemy resistance was unable to stem the forward surge of the division and by 11 September 1944 the division had pushed in force to the `Siegfried Line` at a point approximately six (6) kilometers west of the city of Aachen (Aix-La-Chapelle), the first large German city in the path of the division.

EVACUATION:

The plan for the Marigny breakthrough anticipated no problems of medical evacuation within the division and during this phase of the operation evacuation was normal. One platoon of the 47th Field Hospital which was in support of the division followed along with the functioning platoon of the Clearing Station and set up as required to handle non-transportable casualties. Most of the time, because of the light casualties, this Field Hospital Platoon did not operate and was kept in mobile reserve. Evacuation of the Clearing Station was effected by on Army Medical Group to evacuation hospitals which were initially located within fifteen (15) miles of the Clearing Station. By 17 August 1944 the division was located in vicinity of Bagnoles de L`Orne and here the Clearing Station took over a large hotel which had been used as a hospital by the enemy and was suitably marked with the Geneva Red Cross. Operating room facilities were available

14

here but no German equipment or supplies of any consequence had been left behind by the enemy. The Field Hospital Platoon, which at that time was in mobile reserve, became immobilized by casualties from other units in this area. Consequently on 24 August 1944 when the division began its move across France into Belgium, it did so without the support of the Field Hospital Platoon. Relatively few casualties occurred in this drive and the Clearing Station merely established a `skeleton` set up consisting of one (1) large ward tent (combined Admissions, Treatment, and Evacuation). An idea of the rapidity of the operation can be gathered by the daily movements of the Clearing platoons which employed `leap-frog` tactics as follows:

AUGUST 25 - 60 miles

AUGUST 27 - 25 miles

AUGUST 28 - 23 miles

AUGUST 29 - 27 miles

AUGUST 30 - 27 miles

AUGUST 31 - 28 miles

Total: 190 miles

This rapid movement had left the evacuation hospitals far to the rear and in order to maintain some form of close hospital support for divisional clearing stations, field hospitals were now utilized as small mobile evacuation hospitals located between divisional clearing stations and the evacuation hospitals. This then was the medical evacuation as it existed when the division began the battle of the `Mons Pocket`.

One (1) Clearing Platoon had meanwhile moved to a position just south of Maubeuge and had remained mobilized here anticipating a further move across the Belgian border. However, shortly after its arrival here, hundreds of enemy wounded began to clear to this point; frantic calls and messages from first and second echelons of the medical service reported that hundreds of German casualties were still being collected from the battlefield and would shortly arrive at the Clearing Station. To effect this movement of casualties back to the Clearing Station, the units employed whatever type of organic transportation that was available (3/4 ton, 1 1/2 ton and 2 1/2 ton trucks). In addition captured German vehicles and ambulances were also used. A detailed report on the evacuation of the casualties in the `Mons Pocket` and the serious difficulties encountered at this time are shown in a report of the Division Surgeon, addressed to the CG, 1st US Inf Div, APO 1, US Army. A true copy of this report is included here:

14a

HEADQUARTERS 1ST US INFANTRY DIVISION

Office of the Division Surgeon

APO 1, U. S. Army

7 September 1944

SUBJECT: Evacuation of Patients

TO : Commanding General, 1st US Infantry Division, APO 1, U.S. Army

On September 3rd at 1715 hours the First Medical Battalion (less A, B, C, Company and 1st Platoon `D`) arrived at new site south of Maubege GSGS (1/50,000 Sheet 88 3055895) where approximately 50 enemy casualties were found awaiting evacuation. A clearing station was established at once. Truckloads of wounded prisoners proceeded to dome in so that by mid-night over 350 casualties crowded the area. At 2000 hours the 1st Platoon of `D` joined the company at this area and its resources end personnel were added to those of the functioning platoon (2nd).

At approximately 1800 hours we informed Sgt. Wm Kral (578th Ambulance Company whose 10 ambulances were in the process of evacuating us) to inform his Headquarters of the critical situation that was arising. Informal reports from Regiments and our collecting companies indicated casualties well up in the hundreds. About 1910 hours the Division Surgeon called for 20 ambulances from Corps.

About midnight 2-2 T. Trucks, 2w/C, 5 ambulances from the 3rd Platoon, 578th Ambulance Company and 2 ambulances from 450th Ambulance Company, arrived. The trucks made one trip, the ambulances made 2 trips and did not return thereafter.

Early in the morning of September 4th 7 ambulances from 491st Ambulance arrived and remained with us until the evening of the 5th. On the morning of the 4th we were informed via message from G-4 to expect 30 ambulances, 200 litters and 300 blankets via 51st Medical Battalion, within 3 hours. (Message signed by Lt. Col. Eymer at 0955B).

All that day (4th of September) casualties continued to pour in. Our own transportation was utilized to help the collecting companies and to evacuate selected cases to the P.W. cage after treatment. At 1800 hours the 1st Platoon and Headquarters and Headquarters Detachment moved to new position south of Mons at 315082 where almost immediately enemy casualties proceeded to pour in. At 2100 hours the following message was radioed to G-4 `30 Ambulances not yet arrived, Situation critical. 425 enemy and 20 Americans at old site. 132 enemy at new site. All awaiting evacuation`. At this point Division Medical Service was at an absolute standstill. Any serious enemy action would have been disastrous - we were absolutely immobile with 12 miles separating both platoons and gasoline almost unavailable.

14b

Evacuation of Patients (Cont`d)

On the morning of September 5th 5 additional ambulances arrived from 578th Ambulance Company with 100 litters and 300 blankets. At 1100 hours 4 2 T. Trucks from the clearing company undertook to evacuate the station at the old site (S of Maubege). Two trips were made (the first 120 tiles the second 40 miles). At the same time 2 Headquarters 2 T. Trucks and a captured enemy truck evacuated sitting wounded from the station south of Mons . (One 130 mile round trip was made.)

At about 1800 hours September 5th 10 2 T. Trucks from Army arrived, 3 worked at the Maubege site, 7 at the Mons site making 2 trips each. (By this time the distance involved was shortened by the opening of a Medical installation at La Capelle). The old site Maubege was cleared by 2000 hours.

Shortly after midnight of the 5th, 11 more 2 T. Trucks, 5 1T. Trailers and 10 ambulances arrived and by 0410 hours of the 6th the present site (south of Mons) was completely evacuated.

/s/ James C. Van Valin

JAMES C. VAN VALIN,

Col, Med. Corps,

Division Surgeon

A TRUE COPY:

[signed]

MAURICE S. SCHMIDT

1st. Lt, MAC

Office Executive

15

EVACUATION:

At the stage of greatest confusion the question arose as to the necessity of moving one (1) Clearing Platoon to another location in support of other division troops. In order to get: one (1) Clearing Platoon mobilized for this prospective move, a reconnaissance was made in the town of Maubeuge for a building which could be used as a hospital to hold the enemy wounded. A civilian hospital used by F.F.I. (Free French Forces of the Interior) and staffed by one French male nurse and several French female nurses was found. Fortunately the tactical situation changed and it did not become necessary to carry out this emergency plan. By the morning of 6 September 1944, the evacuation situation had been finally restored to normal and on this day, one (1) platoon of the Clearing Station was able to be mobilized for a forward move in support of the division. A final estimate of the number of casualties evacuated through the Clearing Station during this battle showed one thousand, seventy-nine (1079) enemy wounded and one hundred fifty-two (152) American wounded. The emergencies created by the situation which arose in this area undoubtedly shoved certain deficiencies in the evacuation system. Granted that this situation was an unusual one and not too likely to occur too often, still one must agree that the evacuation system must be sufficiently mobile and elastic to handle any emergency that arises. One can easily picture the confusion that existed at the Clearing Station during this period when as many as five hundred (500) enemy wounded were lying outside the tents awaiting evacuation. One can further speculate on how much more serious this could have been if the weather had been inclement, and going still a step further if these wounded had been our own instead of enemy. The capture of this large number of enemy wounded had bagged about a dozen German Medical Officers and about twenty four (24) German medical soldiers. This captured personnel was utilized for treating and caring for enemy wounded and were in some measure responsible for speeding up treatment of casualties here. The question of the failure of property exchange which occurred in relation to litters and blankets will be taken u below under heading of SUPPLY.

Following the battle of `The Mons pocket` [35 miles south of Brussels ] and as the division advanced to the Siegfried Line on the German Border, evacuation within the division remained normal. Meanwhile, evacuation hospitals had moved into Belgium and the long distances from the Division Clearing Station to hospitals had now decreased. The division had arrived in the vicinity of the German border and the entire Clearing Station functioned with a Field Hospital in support. Between this phase of the operations and the beginning of the battle of Germany certain changes took place in the medical support of the division by Army Medical Groups. These changes will be discussed under `The Battle of Germany`.

SUPPLY:

During the short period prior to the Marigny breakthrough, the divisional medical service had been reequipped and resupplied with items used up or lost in previous combat. Therefore, with the start of this operation there was no grave shortages of medical items. In view of the fact that the casualties during this operation were relatively light, there was no

16

drain on medical supply; furthermore, Army Medical Supply Depots were initially located within a distance which allowed easy and quick replenishment of supplies. Property exchange was normal and the Division Medical Supply was able to keep on hand an authorized overage of litters, blankets, and splints. No problems of supply or supply exchange occurred until the division took part in the battle of `The Mons Pocket`. The tactical situation at this time and the tremendous number of enemy casualties treated at and evacuated from the Division Clearing Station has been previously discussed. It was at this point that certain items of supply were completely used up and property exchange, especially of litters and blankets became faulty and broke down completely. In addition the functioning Army Medical Supply Dumps had been left far behind during the rapid pursuit of the enemy across France. It appears that the property exchange of blankets and litters first broke down at the field hospitals. Here patients were accepted on litters with blankets but no litters or blankets were given back in return. Written `I O.U`s` were given to the ambulance drivers who complained about this practice but these same ambulance drivers were there upon given excuses that hospital property exchange of these same items had broken down at the rear medical installations. The blame was finally put on the evacuation facilities at the `air strips` where it was reported that litter patients were being flown to the United Kingdom but that no litters or blankets were being returned in exchange. It is no wonder that within a very short time all the basic load of litters and blankets plus the excess load of litters and blankets were almost exhausted within the division. At one stage of the evacuation it was necessary to instruct ambulance drivers that in the case of a litter patient if the hospital was unable to effect an exchange of litter and blankets, the patient was to be left at the hospital without the litter and blankets, which were to be returned to the Clearing Station. This critical supply situation was not completely relieved until the morning of 5 September 1944 at which time the Clearing Station received one hundred (100) litters and three hundred (300) blankets. Within forty-eight (48) hours litters were available at Army Medical Supply Depots which meanwhile had moved closer to the Clearing Station site.

Following the battle of `The Mons Pocket` and with the resupply of litters, blankets, splints, bandages, dressings, and plasma, Division Medical Supply was again able to furnish normal supply service on the division`s continued drive across Belgium to the German border. Shortly after the arrival of the division at the Siegfried Line and prior to the battle of Germany, Army Medical Supply Depots set up in the vicinity of Eupen within ten (10) miles of Division Medical Supply and here the requisitioning and supply of all medical items once more assumed normal character.

PERSONNEL:

The only important changes in personnel which occurred during this period were those which had been created by recent changes in T/O. This major change was that which provided one MAC officer (1st Lt.) to assume the duties of Assistant Battalion Surgeon. With this change in the T/O

17

of the Regimental Medical Detachment one (1) Medical Corps Officer assumed the duties of Assistant Regimental Surgeon. Other changes which were not put into effect at this time because they were disapproved by the Division Surgeon, were those turning over the duties of S-3 of the Medical Battalion to an MAC officer (Captain), replacing the Medical Inspector (Major, MC) with either a Sanitary Corps Officer or MAC officer in the rank of either Captain or Major, and removing the Division Veterinarian (Major, VC). These changes involved the requisition of nine (9) MAC Officers who arrived at the division at various intervals. The complete change over was effected by 2 September 1944. Although it had been contemplated with the new T/O changes there would be created an excess of Medical Corps Officers for use in other medical units, no transfers were made and at the end of this period an overage of four (4) Medical Corps Officers existed.

SANITATION AND HEALTH:

The remainder of the month of July and the entire month of August were characterized by hot summer weather and very light rain fall. Roads and bivouac areas were for the most part dry and dusty. Although buildings were available for housing, the weather and the rapid progress of the tactical situation favored the use of open fields and wooded sections for bivouac of troops. This preference for open bivouac areas was further dictated because of the large number of flies which were to be found in and around civilian homes and farms. Fly-control measures within these bivouac areas were continued. Latrine and kitchen discipline was rigidly enforced and consequently fly-borne diseases were kept at a minimum. Mosquitoes were not too prevalent except in certain areas and these were again identified as the Culex variety. At the close of this period the climate underwent a change. Cold weather prevailed and rain fall became heavy. With this decided change in weather, troops again began to billet in civilian establishments and public buildings. Many of the divisional units which were bivouacked in open fields were forced out of these areas to seek cover and protection from the weather in buildings.

Water Supply:

Water discipline continued to be excellent and all water used for drinking and cooking was obtained from controlled water distribution points provided by the division or other military organizations. The streams and fresh water ponds were the primary source of water supply utilized for these purposes. Bathing and laundering were prohibited in these water sources which provided the water used for drinking and cooking.

Waste Disposal:

Again latrine facilities consisted of straddle trenches, `cat holes` and where buildings were available some flush toilets were found and used. All kitchen wastes, trash, rubbish, and cans were disposed of either by burial or incineration. Certain areas within town limits which had been used by the civilians as trash dumps were similarly used by the division. It may be

18

noted at this time that the French and Belgians near these trash dumps made it a practice of `salvaging` much of the rubbish dumped by military units especially wooden crates, card-board boxes, tin cans etc.

Messes:

Messing facilities and kitchens were handled exactly the same as in the previous period.

Food:

This period of operation saw the consumption primarily a `B` ration. The emergency field rations were used only when the tactical situation required. Fresh meats, fresh bread, and butter etc, became a frequent issue and because of a good variety in the ration issue supplementing the messes by local purchases practically disappeared; at no time was it felt that the diet should be supplemented with vitamins.

Diseases:

Malaria: Malaria and FUO`s showed no evidence of decreasing and during the month of August there were reported three hundred ninety-two (392) cases of Malaria and one hundred forty (140) cases of FUO`s. All efforts were still directed toward controlling the disease by use of atabrine prophylaxis. It is felt that a weakened resistance of the men due to continued combat was a contributing factor to the increased incidence of the disease. It was further believed that none of these cases were other than an exacerbation of chronic malaria which had had its origin in the Mediterranean Theatre.

Venereal Disease: As in the month of` July only one new case of venereal disease was reported for the Month of August. This low venereal rate was attributed to the fact that the division was in combat, and that social contact between military personnel and civilian personnel was practically non-existent.

BATTLE OF GERMANY, 12 SEPTEMBER 1944 TO 31 DECEMBER 1944:

Having reached the Siegfried Line the tactical mission now confronting the division was the breaching of this formidable defense. The Siegfried Line is best described as a system of defense made up of several `belts` manned by pill boxes, machine gun nests, barbed wire tank traps, `dragons teeth` and other field fortifications. Without any let up the division started its push through the Siegfried Line on 12 September 1944. The push forward was relatively slow and in the face of a more organized German defense. Artillery was much more active and the troops manning the Siegfried Line were apparently of a higher calibre than the division had encountered since its breakthrough at Marigny. However in spite of the determined defense and the small infantry end tank counter-attacks, the Siegfried Line was completely breeched on the 15th of September 1944 by one (1) regiment of the division. However two days later an entire

19

new German division which was one of the best we had encountered to date in the European campaign took up a position in front of the division centre. The defense set up by this unit was stubborn and well coordinated, and the terrain lent itself to defensive tactics. The push toward the big industrial city of Aachen was slow and every house in the small towns on the road to Aachen was stubbornly defended. By 1 October 1944 Aachen was contained on three sides, West, south and east. Meanwhile the enemy had refused to offer to surrender and prepared to defend the city. The ensuing battle became known as `The Battle For Aachen`. It lasted until the 21 October 1944 at which time the city was surrendered. The total number of prisoners taken by the division was almost six thousand (6000). The slow and methodical clearing of this city by the division served to keep casualties relatively low. It was the first time since being in combat in this wav that the division had fought this type of battle, namely house-to-house and street-to-street fighting which occurs in the prepared defense of a large city. Futhermore this type of fighting produced certain problems of evacuation which will be discussed below.

With the surrender of Aachen operations died down to active patrolling and the enemy`s improvement of his defensive positions. The next mission of the division can be described as the attack toward the Roer River. This river was one of the natural barriers protecting the city of Cologne and the Ruhr industrial sector along the Rhine River. On the 10th November 1944 the division moved to the Stolberg area for this attack. Due to extremely heavy rain fall which created tremendous problems of movement and transportation the attack was postponed until the 16th November 1944. The area of attack was northeast through thick woods (Hurtgen Forest), and with few passable roads. Several hills in the heavy forest provided natural advantages to the enemy; the town areas were well fortified and the enemy had made use of his time to lay intensive mine fields, set up rows of barbed wire, and to dig in among the heavy trees and dense underbrush. The subsequent operation was one of the most difficult the division had engaged in on the continent.

The following conclusions taken from selected intelligence reports of G-2, 1st US Infantry Division, will describe in brief the difficulties encountered by the division.

`a. There is no doubt that enemy resistance to the 1st US Infantry Division offensive of 16 November, was as tenacious and determined as any encountered in the Division`s campaigns. By virtue of his stubborn reluctance to give up so much as a foot of defendable ground, the enemy was able to inflict a considerable number of casualties on our troops. In this he was aided by a terrain which was as unrelenting as the enemy himself. The deep woods in which the 26th US Infantry forced its way precluded the use of any support weapons except those which could be carried through the mud and underbrush on a man`s back. Enemy mortar and artillery fire, even heavier during this offensive than the concentrations laid on the VERLAUTENHEIDE Ridge in the Battle for AACHEN, was increased in effectiveness by the high percentage of tree bursts obtained in the woods. Furthermore, the enemy was retreating over terrain which he knew intimately, and on which he had registered his artillery. At the close of the period it was estimated that the enemy artillery was equal in number to our own, the first time that such an unadvantageous ratio had prevailed.

20

b. The morale of the enemy troops, by all previous experience, should have been shaky. It was not. Small groups, surrounded and cut off, refused to surrender. If the German command often sent suicidally small forces to perform what should have been battalion or even regimental missions, at least those forces fought until they were exterminated. Never before has the 1st Division encountered an enemy regimental commander personally directing local counter-attacks, yet it happened during this operation, when the colonel commanding the 104th Regiment was captured fighting an isolated and essentially hopeless engagement.`

It was estimated that over three thousand (3000) prisoners were captured by the division and two (2) divisions almost completely destroyed.

By 6 December 1944, the division had completed its penetration of the Hurtgen Forest. and had reached its objectives on the main east west road from Aachen to Duren at a point about four (4) miles from Duren . Here the division was replaced in the line by the 9th US Infantry Division and withdrawn to an area west of Aachen to undergo a so-called rest period, which incidentally was the first time since the D-day landings on the continent 6 June 1944 that the division had been officially withdrawn from the line. However, this rest period favored only two combat teams of the division since one combat team was attached to V Corps to take up a defensive sector in the Monschau area. During the rest period short passes and leaves, (48-72 hrs) were granted to enlisted personnel and officers. Recreational trips were made to Paris and other large cities in Belgium. Reorganization in every sense of the word was put into effect.

On 13 December 1944 the one combat team which had been on detached service returned to division control and likewise started its rest period. But on 16 December 1944 with the start of the counter-offensive by Rundstedt against the First US Army, the division was placed on a six (6) hour alert, and on the morning of 17th December 1944, one combat team of the division moved into a defensive sector just south of Monschau (Ardennes Forest) to protect Liege. This one combat team was followed by the rest of the division within twenty-four (24) hours. One (1) combat team took up its position east of Malmedy and the other combat team was given the mission of rounding up or destroying German parachutists which had been dropped in the vicinity of Eupen.

These paratroopers failed to accomplish their mission which was primarily to block the arrival of reinforcing troops. A strong crosswind and an inadequate briefing of the JU-52 pilots scattered the units and their weapons and equipment over an area far wider than planned. Much of the equipment was lost and damaged; radios were knocked out and failed to function. About all these paratroopers accomplished was a harassing of a few isolated vehicles and the taking of a few prisoners. Under these circumstances it was not long before the majority of parachutists had been rounded up and for many days members of this group kept showing up all over the area and turning themselves into whatever American troops they could find. By the 19th December 1944 this combat team had carried out its mission and had taken its position in the line.

21

The following data on this military situation has been taken from G-2 periodic report #201, 1st US Infantry Division.

`On 16 December 1944 the enemy launched a high-geared meticulously planned counter-attack on the centre of the First US Army line between Monschau and Echternach The ultimate objectives of this drive were the allied supply port of Antwerp and the big communications center of Brussels intermediate; objectives were the Meuse River and the city of Liege. One of the primary objectives and the one most necessary for the success of this operation was the seizure of the enormous American supply dumps in Liege, Verviers, and Eupen area. The initial attack was spearheaded by the 1st SS Panzer Division and 12th SS Panzer Division. Initially the breakthrough was carried out according to plan. The 1st SS Panzer had pushed deep into this sector and was followed by the 12th SS Panzer whose mission apparently was to roll back the northern flank and advance toward the American supply dumps. This was the situation that existed when the division (initially one (1) combat team) arrived in this sector. The first attacks of the 12th SS Panzer were beaten off on the 17th December 1944. On the 19th December 1944 more heavy counter-attacks were beaten off with losses to the enemy in both personnel and materiel. By this time the 1st SS Panzer which had penetrated deeply was in serious straits because of the 12th SS Panzers` failure to clean up the northern flank. The 3rd Parachute division (German) was brought in on the 20th December 1944 to support the enemy`s frantic attempts to break through this position and on the 21st December 1944 the enemy`s major assault was launched. After a day of heavy fighting the attack was defeated and although in the subsequent days, he still continued to attack fiercely, he achieved no success. With the collapse of his plan to force his way north, the enemy subsided into the defense, bringing up Infantry units to dig in and hold the line while the badly mauled 12th SS Panzer was withdrawn for repairs.`

EVACUATION:

Up until the beginning of the battle for Aachen evacuation was well organized and quite normal. The vicinity of Eupen was set up as the center of all medical installations including hospitals for patients with special diseases or casualties. Evacuation hospitals took the majority of patients and casualties; 622nd Separate Clearing Company was designated as the Exhaustion Center and accepted all Neuro-psychiatric (NP) cases; 91st Medical Gas Treatment Battalion took care of Malaria, communicable and contagious diseases and self-inflicted wounds (SIW`s); 633rd Separate Clearing Company received patients with respiratory diseases. In addition, the Corps Clearing Station (50th Medical Battalion) was set up to act as a holding platoon for patients who would be able to return to duty within ten (10) days; these patients returned direct to duty back through the Division Clearing Station. Because of this specialized handling of patients, evacuation was controlled through an Ambulance Regulating Point which triaged the patients and dispatched them to the various hospital installations. Field hospitals were likewise located in same general vicinity but most of them kept in mobile reserve. At this time the division was being supported by the entire complement of a Field Hospital. This was a decided improvement over previous plans

22

when the division was supported by only one platoon of a Field Hospital. Because of the fact that the Division Clearing Station was within five (5) miles of the nearest evacuation hospital the Field Hospital did not function and non transportable patients were evacuated directly to the evacuation hospital.

The Division Clearing Station did not move at anytime during the penetration of the Siegfried Line and the capture of the city of Aachen. Only one combat team of the division was actually engaged in the house-to-house and street-to-street fighting within the city limits of Aachen. Previously evacuation forward of the Battalion Aid Stations was generally accomplished by `jeep` ambulance or litter bearers. Within the city itself, `jeeps` could be used almost exclusively in retrieving wounded and returning them to the Battalion Aid Stations. However, with the large amount of debris, especially glass, which cluttered up the streets of the city, frequent tire punctures of the `jeeps` occurred. As many as twelve (12) punctures were reported in one day by the driver of one of these `jeep` ambulances. To prevent the slowing up of evacuation, `weasels` (tracked `jeeps`) were substituted and worked out very well. These tracked `jeeps` were able to cross any difficult terrain and could be improvised to hold two (2) litter patients. At times during the advance through the city the Battalion Aid Station was split. Telephone communication was maintained between these stations and the rifle companies so that the Battalion and Assistant Battalion Surgeon could immediately dispatch a `weasel` or litter bearers to a point where casualties had occurred. This tended toward a smooth and rapid evacuation. All possible protection was given to the Battalion Aid Station by installing them in well-protected cellars or air-raid shelters.

The medical plan for the attack towards the Roar River which began on 10 November 1944 anticipated that because of the terrain, the weather, and the poor road network the use of motor transportation for evacuation of casualties within the forward areas would almost be impossible; therefore, extra litter bearers were obtained from higher headquarters and placed with each Collecting Station to assist in the evacuation forward of the aid stations. Initially, eighty (80) litter bearers were obtained but by the time that the division had penetrated the Hurtgen Forest, approximately two hundred forty (240) litter bearers had been employed. Litter carries were very difficult and averaged two thousand (2000) yards. Enemy artillery and mortar fire which create bursts in the forest caused a large number of casualties among these litter bearers. These two hundred forty (240) litter bearers were not used at one time but constituted the number of personnel needed to maintain approximately eighty (80) litter bearers in all Battalion Aid Stations at all times. At times when casualties were even greater than could be handled by this complement of litter bearers, basic infantry were drafted for duty as litter bearers. Casualties during this period were heavy. To conserve the use of ambulances, other organic transportation (3/4 ton, 1 1/2 ton and 2 1/2 ton trucks) were used to evacuate walking wounded not only from Collecting Stations to Clearing Station but also from Clearing Station to hospitals. In addition to being heavy, many of the casualties were very severe. One Field Hospital Platoon set up close to the Clearing Station and all non-transportable patients were evacuated there and treated. On 21 November 1944, the Clearing Station treated and

23

evacuated five hundred one (501) patients (including enemy casualties) in a twenty four (24) hour period.

On 5 December 1944 following the completion of its mission in the attack towards the Roar River, the division was relieved and bean its return to its rest area by infiltration. This relief and return to rest area involved only two combat teams. One combat team was now detached from the division to take up a defensive sector in the vicinity of Monschau. In view of the fact that this combat team would be dispersed quite widely a special system of evacuation was put into effect. The Collecting Station attached to this combat team was in a position to evacuate only two (2) of the Battalion Aid Stations of this combat team. It was able to clear these patients through a Clearing Station of another infantry division. The other battalion of the combat team carried out its evacuation direct from Battalion Aid Station to hospital. To accomplish this extra ambulances from the Collecting Station were attached. This system of evacuation was no problem except from the standpoint of administration with respect to reports on casualties. Evacuation of this detached combat team reverted to normal when it again went under division control on 16 December 1944 with the beginning of the German counter-offensive through the Ardennes Forest , the division was immediately committed to defend part of the northern boundary of this salient. Because of the confused situation, no Clearing Station was moved to this sector to effect evacuation. The one combat team which first arrived in this area evacuated through its attached Collecting Station to Clearing Station of other infantry units nearby. The second combat team which was committed to the same sector shortly thereafter effected its evacuation in, the same manner. However, the third combat team which had the mission of protecting the city of Eupen from parachutists, because of the closeness of hospitals in Eupen evacuated directly from Collecting Station directly to hospital. After several days when the tactical situation had cleared and when the entire division joined together to set up a defense, one platoon of the Clearing Company was moved down into this area and resumed normal evacuation of patients.

During the early days of the counter-offensive when the threat to Eupen was serious, many of the hospital installations moved out, thus creating a lack of facilities for holding patients or casualties; thereupon the platoon of the Clearing Company which was north of Eupen was set up as a holding platoon to handle patients who were expected to be ready for duty within seven (7) days. This platoon expanded to a capacity of seventy-five (75) beds. Between the 24th and 28th of December 1944 the, forward operating Clearing Station underwent shelling by enemy artillery apparently directed against artillery batteries located in the vicinity of the Clearing Station. Several of the ward tents were pierced by shell fragments, some of the vehicles were damaged, and the house which was being used as the treatment station was damaged by shell fragments. Because of this the Clearing Station moved back to a new location out of enemy artillery range. On the last day of the year the evacuation setup for the division was normal; no Field Hospital was in support of the division at this time. Evacuation hospitals were located about five (5) miles from the Clearing Station. Because of the limited hospital facilities except for those patients held in our own Clearing Station, evacuation was total.

SUPPLY:

At no time during this period was any difficulty experienced in procuring medical supplies. The Army Medical Supply Depots were well stocked and able to fill the entire needs of the division. With the change in the treatment of `New` Gonorrhea with Penicillin this drug was easily obtained from evacuation hospitals. For a short period of time certain biological products were critical especially Typhus Vaccine but the shortage soon eased. When the German counter-offensive of 16 December 1944 had broken into the First Army lines it overran a numbed of medical installations especially field hospitals. When the division had taken back some of the lost ground in this area it recovered some of this field hospital equipment. This included microscopes, haemocytometers, surgical instruments, generators, tentage and etc. This recaptured equipment was turned into higher headquarters through channels.

PERSONNEL: