AMEDD Corps History > U.S. Army Dental Corps> Walter D. Vail and the History of the U.S. Army Dental Corps

DENTAL BULLETIN SUPPLEMENT TO THE ARMY MEDICAL BULLETIN

VOLUME 4, NO. 3 (JULY 1933)

103

A STUDY OF DENTAL CONDITIONS OF OFFICERS OF

THE ARMY WITH REFERENCE TO THE LOSS OF

TEETH AND THEIR REPLACEMENTS.

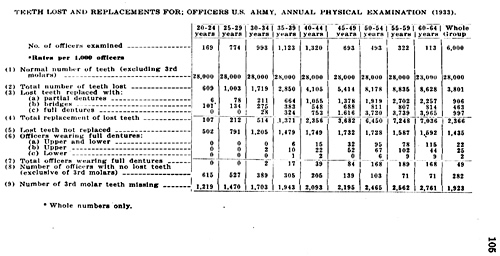

Introduction.—Tabulated data appearing on page 105 represent the results of a study of 6,000 reports of Annual Physical Examination, Form 63, A.G.O., made for the purpose of determining the extent of loss of teeth by officers in the Army and the replacement of lost teeth with prostheses. The records examined were not a selected group, they were the first 6,000 received in the office of The Surgeon General for review. However, they were received from practically all stations, foreign as well as domestic, and it is believed that they are the records of a representative group of officers. This opinion is further confirmed by the fact that after 2,000 records had been examined and tabulated, the findings for additional groups produced the same uniform results and the effort was discontinued with 6,000, although it was originally intended to review 10,000 reports.

Explanation.—The data are collected into age groups of five years each, beginning with 20-24 and ending with 60-64. The number of officers examined is shown under each heading. Since third molars are not constant they are not considered a factor in this study. They were counted as a control measure (Line 9). Excluding third molars, the adult individual would normally possess 28 teeth and since the tabulation is based on rate per 1,000 officers, the normally expected 28,000 teeth per 1,000 officers in each age group is shown to simplify comparison (Line 1). Thus in the first group (20-24) the rate was 609 teeth lost per 1,000 officers, or .6 tooth per individual. In the 55-59 group the rate was 8835 teeth lost per 1,000 officers, or 8.83 teeth per individual (Line 2).

Rate of loss of teeth.—The rate of loss of teeth increases with the advance in years except in the 60-64 group. In the 6064 group the loss rate (8.628) is lower than in the 55-59 group

104

(8,835) and is probably due to the fact that separations from the Army at the age of 60 or thereafter remove many officers from active service who have large numbers of missing teeth (Line 2).

The increase in the rates per 1,000 from the 20-24 group (609) to the 55-59 year group (8,835)—a period of thirty-five years—is 8,226, or an average of 235 per year. Using the same method, the yearly rates for succeeding groups are: (25-29) 231, (30-34) 285, (35-39) 299, (40-44) 315, (45-49) 342, (50-54) 131, or an average yearly rate of 267 per 1,000 officers for the whole group. The greatest yearly rate is found in the 45-49 group (342). Based on this experience the greatest loss of teeth for officers is to be expected between 45 and 50 years of age.

Extent of loss of teeth .—615 officers per 1,000 (or 61.5% ) in the 20-24 group possess the normal complement of 28 teeth, in the 60-64 year group only 71 per 1,000 (or 7.1% ) possess the normal number of teeth (Line 8). 6 officers per 1,000, or 1 in every 167 officers, in the 35-39 year group are edentulous, in the 60-64 year group 1 in every 9 officers is edentulous. In the whole group of 6,000 officers 22 per 1,000, or 1 in every 45 officers, wear full upper and lower dentures (Line 6a); 49 per 1,000 or 1 in every 20 officers wear full dentures, either full upper, or lower, or both (Line 7).

The edentulous age.—The edentulous age refers to the number of years a group of individuals would become wholly edentulous as the result of a given rate of loss of teeth. The “edentulous age” is a relative term that may be used to interpret rates of loss of teeth and has the same relative application with reference to the loss of teeth as “expectancy of life” has in mortality tables. It is obtained by dividing the rate of loss of teeth per 1,000 per annum into the actual number of teeth any group of 1,000 individuals has. For example: The 20-24 year group of officers has lost 609 teeth. 28,000 minus 609 equals 27,391. The average annual rate of loss of teeth for the whole group of 6,000 officers was 267. 27,391 divided by 267 equals 103. Thus the edentulous age for that group is 103 years. Applying extraction rates experienced by the whole Army in 1931, (567 per 1000 officers) the edentulous age -would be 48 years (27,391 divided by 567).

105

106

Replacements.—The rate of replacements falls considerably behind the rate of non-replacements until the 35-39 year group is reached, when the rates approximate (Line 4). In the 20-24 year group the number replaced is approximately 1 to 5 not replaced, in the 25-29 year group 2 to 7, in the 30-34 year group 5 to 12. After the 35-39 year group the replacements greatly increase over the non-replacement rates, and in the 60-64 year group the replacements are 7 to 1.5 non-replacements (Lines 4 and 5).

Dentures and partial dentures predominate as types of replacements. Partial dentures are found in all groups (Line 3a); full dentures are found beginning with the 30-34 year group (Line 3c). The youngest officer wearing a full denture (upper) was 30 years of age; the youngest officer (two) wearing full upper and lower dentures were 36 years of age. It is interesting to note that beginning with the 50-54 year group the number of teeth replaced by full dentures (Line 3c) exceeds the numbers replaced by bridges and partial dentures combined (Lines 3a, b), It seems appropriate, therefore, to refer to the 50-54 year group as the beginning of the “denture age.”

Summary.—In the whole group the rate of loss of teeth is 3.80 teeth per officer; of these 2.37 teeth have been replaced, leaving 1.43 teeth per officer not replaced. The ratio for replacements is 1.00 for full dentures, .46 for bridges, and .90 for partial dentures.

Comment.—The findings that 1 of every 45 officers wears full upper and lower dentures and that 1 of every 20 officers wears full dentures (either upper or lower, or both), impress one with the toll exacted by dental diseases. It is a narrow view, perhaps, to consider the ravages of dental diseases from the viewpoint of the mere loss of teeth. Yet the loss of a tooth usually represents the end-results of dental disease; it means that the resultant condition is a menace to health and should not be tolerated. Relatively few teeth are wholly lost from external causes.

The extent of loss of teeth shown in this study indicates the performance of a vast amount of health service and unquestionably a large portion of it was done in conjunction with, and as a part of, medical attendance for the restoration of health.

107

The removal of dental infections is, in general, a distinct health service. On the other hand, the gross loss of teeth is evidence of failure to provide a far more valuable health service—that of preventing and controlling dental diseases which if even reasonably controlled, would afford an important and economical factor in the maintenance of health. It is more economical to perform simple operations for the prevention and control of dental diseases than it is to extract teeth and construct prosthetic appliances, which are in themselves expensive, to say nothing of the time involved, that could be more profitably employed in control service. If, however, the less expensive measures are not made available, the more expensive ones must be employed to meet the situation.

It is to be hoped that the toll exacted by dental diseases will receive the attention it deserves and that measures for the reduction of the toll will be instituted to the end that health may be conserved by preventive rather than restorative procedures.

W. D. Vail,

Major, Dental Corps.