AMEDD Corps History > U.S. Army Dental Corps > United States Army Dental Service in World War II

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

In the administration of the Dental Service in theaters of operations,it was at first believed that the flexibility needed to meet rapidly changingsituations could be attained only by assigning dentists directly to thesmall organizations which they were expected to serve, together with equipmentwhich could be moved on short notice and set up near the actual combatarea. Such assignments were made to small units the size of a battalionor regiment, in each of which 1 or 2 dentists were responsible for thecare of from 400 to 3,000 men.

The unit dental officer was normally part of the organization medicaldetachment, responsible directly to the unit surgeon and through him tothe unit commander. He was concerned mainly with the care of the men ofhis own organization and was involved very little in the problems of theDental Service as a whole. His relation to the dental surgeon of a higherheadquarters was often vague; the latter might offer technical advice,but the unit surgeon actually exercised direct supervision over the dentalsurgeon's activities. Under such control, the unit dental service had theadvantage of flexibility; without waiting for specific orders from higherauthority the dental officer and his equipment accompanied the commandwherever it might move. Unfortunately, however, there resulted a systemof highly dispersed, loosely supervised dental installations with certainvery serious weaknesses.

Two of the outstanding defects of the unit dental. services, the difficultyof providing uniform dental care in the larger commands and the inefficientutilization of dental personnel, are discussed in connection with the dentalservice of a division. A third difficulty was the practical impossibilityof making an equitable assignment of dental officers to separate smallorganizations.

In much of the period between World Wars I and II dental officers wereprovided in an overall ratio of 1 dentist for each 1,000 men. Some officerswere required for hospitals and administrative positions, however, andthe number available for field units was therefore somewhat less than thisfigure. In the absence of any formal policy, a ratio of 1 dentist for each1,200 men in tactical commands seems to have been generally accepted; thisratio was eventually made official in 1943.1 But since veryfew units had a strength of exactly 1,200 men, or a multiple of that figure,the application of any fixed ratio was not simple. Even if the doubtfulassumption that 1 dental officer could care

1WD AG Memo W310-9-43, 22 Mar 43, sub: Policiesgoverning tables of organization and tables of equipment. AG: 320.2.

288

for 1,200 soldiers was accepted, what was to be done about the organizationwith 600 men, or the one with 1,800 men? In the final analysis each casestill had to be decided on its own merits, and many unsatisfactory compromiseswere necessary. Some commands which would have been entitled to a dentistunder the prescribed policy were allowed none if it was felt that theywould be able to get attention from nearby units, while smaller commandswere sometimes given a dental officer when they were expected to functionindependently.

The Dental Division recognized the need for a more equitable distributionof dental personnel. In 1944, with the approval of The Surgeon Generaland the Air Forces, it recommended that 1 dentist be authorized for each1,000 troops. At that time the proposed increase was disapproved by GroundForces and Army Service Forces, and even by the end of the war when itwas clear that fundamental changes were needed in the tables of organizationof tactical units, no further action on this recommendation had been taken.

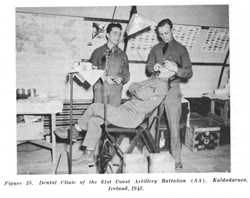

Figure 25. Dental Clinic of the 61st Coast Artillery Battalion (AA). Kaldadarnes, Iceland, 1942.

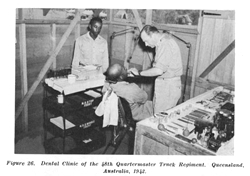

Figure 26. Dental Clinic of the 48th Quartermaster Truck Regiment. Queensland, Australia, 1942.

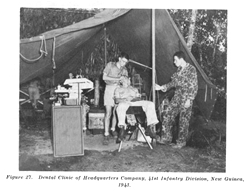

Figure 27. Dental Clinic of Headquarters Company, 41st Infantry Division, New Guinea, 1943.

290

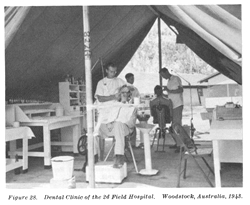

Figure 28. Dental Clinic of the 2d Field Hospital. Woodstock, Australia, 1943.

DENTAL SERVICE OF A DIVISION

In the administration of the dental service the division was an importantorganization for it was the smallest complete combat team comprised ofmany arms and services in which coordination of the activities of individualdental officers could be attempted. The division dental service, however,was a very loosely organized activity. It consisted essentially of theseparate unit dental services of its component commands, supervised bya division dental surgeon.

At the start of World War II the dental service of a "square"infantry division numbered 30 officers under a division dental surgeonin the grade of colonel. In the "streamlining" of the divisionto its "triangular" form during the early part of the war thisfigure was reduced by approximately one-half, otherwise the internal organizationof the dental service was changed only in minor details. With somethingless than 15,000 men the infantry division was authorized 12 dentists.One, in the grade of major, was assigned to the medical section of divisionheadquarters as division dental surgeon. Eleven dentists, captains or lieutenants,were assigned to the larger component tactical units as follows:2

2T/O&E 7,15 Jul 43.

291

| 3 Infantry regiments (3,256 men each) | 6 |

| Division artillery (2,219 men) | 1 |

| Engineer battalion (664 men) | 1 |

| Special troops (943 men) | 1 |

| Medical battalion (469 men) | 2 |

One of the first responsibilities of the division dental surgeon wasto coordinate the activities of seven or more separate dental servicesto provide equitable care for the organization as a whole. Under the systemofficially in effect during most of the war, this task involved formidabledifficulties. Many smaller units had no assigned dental officers; moreover,the division was commonly reinforced with a number of auxiliary commandswhich were also without their own dentists. The total strength of these"orphan" units might reach several thousand men. In theory thepersonnel of the smaller organizations were expected to receive dentalattention from the officers of nearby regiments or battalions, but in practicethey were often given treatment under protest, if at all. The dentistsof the larger units, who were individually responsible for a thousand ormore men, were naturally reluctant to neglect their own troops to carefor adjoining commands, and in this attitude they usually had the fullsupport of their commanders and surgeons. The General Board of the Europeantheater found that "personnel of units whose tables of organizationdid not authorize dental personnel received as a rule only mediocre dentalservice. These units depended upon dispensaries, hospitals, clinics, andother units in the area for their dental care, and in most instances theemergency cases only received attention."3 Even among unitswith assigned dental officers there was no uniformity in the quality ofthe dental service provided. The dental officer of the engineer battalion,for instance, was able to render adequate treatment for all his 664 men,but the dental officer with the division artillery could meet only a fractionof the needs of his 2,219 soldiers. Even with unlimited authority the solutionof this problem would not have been simple, and the practical powers ofa division dental surgeon were anything but unlimited.

As previously stated, the dental officer of any individual unit wasdirectly under the surgeon of that unit, who in turn was under the ordersof the commanding officer. By tradition and necessity the commander hadcomplete control over all personnel under his supervision, and higher authoritywas extremely reluctant to disturb internal matters so long as major policiesor directives were not violated. The local commander's first responsibilitywas for his own men, and any proposal to use a dental officer outside theorganization, or for the benefit of other troops, was almost certain tomeet with prompt and vigorous opposition. As a staff officer, on the otherhand, the division dental surgeon generally had no authority to issue orders.He could make recommendations to dental officers and commanders, but neitherwas obligated to accept his counsel. If his advice on an important matterwas rejected his only

3Rpt, General Board, ETO, Study 95, Medicalservice in the communications zone in the European Theater of Operations.HD: 334 (ETO).

292

recourse was to present his problem to the division commander throughthe division surgeon. If approved, an official order could be sent throughchannels to the dental officer concerned. Approval of an action opposedby high-ranking subordinate commanders was very difficult to obtain, however,and the division dental surgeon, in the grade of major, who attempted tohave a dental officer temporarily released from an infantry regiment commandedby a senior colonel often faced a fight to the finish. At best the procedureof issuing a division order was too ponderous to be of much help in makingthe frequent minor adjustments necessary to meet a rapidly changing situation.The following account is typical of the problem sometimes encountered bydental staff officers:

In 1943 the dental surgeon of the Middle East theater found that thedental officer of a unit which had been cut to about 400 men was beinggiven full-time duty in administrative work, principally as court-investigatingofficer. On the same post three dental officers of other organizationswere vainly trying to meet the needs of several thousand men, includingthe personnel of the unit in question. The unit commander flatly refusedto release his dental officer for duty in the post clinic, or even to placehim on professional work with his own personnel. The next higher commanderadmitted the need for corrective action but refused to interfere in whathe considered the internal administration of the subordinate unit. Thetheater commander, in turn, did not consider the utilization of a dentalofficer a sufficiently important matter to warrant reversing the decisionof another senior commander. In this particular case it was eventuallypossible to have the dentist transferred to another unit on the groundsthat the original organization had been reduced in strength to a pointwhere assignment of a dental officer was no longer necessary, but eventhis step was attained with difficulty and at the expense of the ill-willof the commander concerned.4

Surgeons and line commanders, like dentists, were only human; in somecases they did not exercise, perfect judgment in dealing with dental problems.Nevertheless, they cannot be blamed for the main defects of the divisiondental service. Both were only exercising the established rights of anycommander, and both felt that they were showing only praiseworthy concernfor the welfare of their men when they refused to release a dental officerfor temporary duty where his services were more urgently needed. Only acomplete revision of the division dental organization could avoid the difficultiesinherent in an attempt to provide uniform dental care with a number ofsmall, independent, unit dental services.

Another problem of the division dental surgeon was keeping all unitdental officers performing professional duties whenever possible. In areinforced division each dentist might have to care, for as many as 1,500men, and even the minimum needs of such a population could be met onlyif each

4Personal experience of the author who wasdental surgeon of the Middle East theater at the time these events tookplace.

293

dental officer devoted all his time to the duties for which he was trained.Yet on the dentists of units in combat could not operate clinics underfire and for weeks at a time could render only emergency treatment or actas assistant battalion surgeons.

As the war progressed it became increasingly evident that a more efficientuse of tactical dental officers was imperative. A unit which entered combatin good condition could go for some time with emergency dental care only,plus the sporadic attention that was available between periods of fighting,but lack of definitive treatment eventually resulted in reduction of combatefficiency due to excessive evacuations for dental causes.5

Almost every World War II division ultimately attempted some modificationof its dental service in an effort to improve the efficiency of dentalofficers assigned to combat units. The War Department apparently did notwish to prescribe any rigid reorganization however, until the more promisingsuggestions had been tested under field conditions, and no official changewas published until near the end of hostilities. Most improvements weretherefore made on the personal initiative of progressive dental officers,with the help and advice of farsighted surgeons and line commanders. Thefinal result, which differed in almost every organization, depended uponthe individual ideas of the dental surgeon and the support received fromhis superiors. In a few divisions where dental surgeons were given completecontrol of all dental personnel and facilities, a near-ideal type of servicewas possible. In one such division the dental service was organized asfollows:6

The division dental surgeon kept the dental survey records showing thecondition of the command and supervised the operation of all dental facilities.One dentist of the medical battalion acted as division prosthodontist andoperated the dental laboratory. The remaining 10 dental officers were assignedto staff 2 clinics. Each of these clinics had its own electrical generatorand tentage and could be employed alone if necessary. Both clinics mightbe set up near the clearing station, or either or both might be moved onshort notice to some location where they were more urgently needed. Onthe rare occasions when all combat units were committed to action the clinicsworked for service personnel and for replacements. Treatment for the latterwas particularly important since many hundreds might arrive in a singleday and many needed care before they were assigned to combat organizations.The advantages of this type of division dental service became most apparent,however, when an infantry regiment or other combat unit was withdrawn fromaction. When the command arrived at its designated rest area it found aclinic staffed by at least five dental officers. It was equipped with electricengines and lights and so organized as to use the special skills of allits personnel.. With such a

5History of the Dental Division, Hq, ETO, 1Sep through 31 Dec 44. HD.

6The dental service described is that of the 8th Div, 9th Army,ETO. Info furnished by Brig Gen James M. Epperly, former dental surgeon,9th Army.

294

concentration of dental facilities it was possible to complete a greatamount of work in a short time and no dental officer wasted his effortsin nonprofessional duties or tried to operate under hopelessly adverseconditions. If necessary, single dentists could, of course, be sent toindividual units, but the improvement in dental care for the whole commandwhich resulted from the procedure just outlined greatly lessened the needfor emergency treatment even in the small organizations. Though the dentalservice remained under the ultimate control of a medical officer (the divisionsurgeon) this experienced senior medical officer who was more interestedin the dental welfare of the whole command than was the average regimentalsurgeon, saw to it that service was impartially rendered to all elements.

In divisions where similar plans were effected the reaction of bothdental officers and line commanders was uniformly favorable. (One armoreddivision disapproved the centralized dental service because it was believedthat individual officers were given an incentive for better work when theywere responsible for the same troops at all times, but this division hadnot actually tested the plan.) It was found that with centralization eventhe larger organizations received much better care than had been possiblewhen their own dentists had tried unaided to meet the needs of their commandsin the short intervals between actions, while the smaller units were ableto get treatment on the same basis as the larger. An effective divisionprosthetic service was provided and dental officers worked under conditionswhich promoted maximum efficiency. Line commanders were relieved of theunfamiliar responsibility for the Dental Service of their commands andtheir traditional rights were not compromised since the dentist was nowassigned directly to a medical unit.

The increased output attained by centralizing the division dental serviceand placing it under immediate dental control was surprising even to thesponsors of such plans. One division in Europe reported that during thefirst week of operation 5 dental officers in a central clinic produced17 times as much work as they had when working with their individual units.7During periods of combat the output of 10 dental officers of thisdivision had previously fallen to 40 percent of the theater average (combatand noncombat) and to only 20 percent of their own noncombat average. Withinauguration of the central clinic in a rear area the same officers completedmore than four times the theater average of work even during combat, andduring the exceptionally unfavorable circumstances existing in December1944 their output still exceeded the theater average by 70 percent.

By the end of 1944 the Dental Division felt that sufficient experiencehad accumulated to justify an effort to have a revision of the divisiondental service authorized in tables of organization. Three senior officerswho had been dental surgeons of armies or major theaters were requestedto submit a joint

7Annual Dental Rpt, 8th Div, ETO, 1944. HD.

295

Figure 29. Dental Survey in European Theater, 1944.

296

Figure 30. Waiting Room of Dental Clinic, 66th Infantry Division, France, 1945.

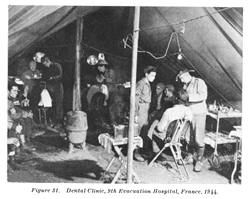

Figure 31. Dental Clinic, 9th Evacuation Hospital, France, 1944.

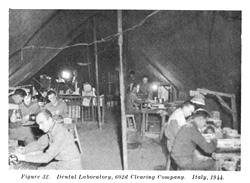

297

study of the dental service in the field. On 8 February 1945 they reportedto the surgeon of the Army Ground Forces as follows:8

Under the present method of assignment of dental officersto various units within the division the control and disposition of thedivision dental service by the division dental surgeon is greatly hampered.He may desire to utilize certain dental officers in other than their assignedunits, and if the regimental or unit surgeon objects the dental surgeonis often overruled since the regimental or unit commander accepts the adviceof his surgeon. . . . The unit surgeon's view is often selfish, being concernedonly with his organization. For maximum efficiency the dental service ofa division must be flexible, and if flexibility is obtained the dentalofficers can be busily engaged in constructive operational procedures underpractically all conditions. . . . The dental needs of a division requirethe full and most efficient utilization of its dental personnel in dentalcapacities at all times. To secure this the following outline of a divisionaldental service is offered:

a. The division dental service to consist of a divisiondental detachment directly under the division dental surgeon, whoin turn functions directly under the division surgeon.

b. Detachment to consist of:

| Division dental surgeon | 1 |

| Prosthodontist | 1 |

| General operators | 10 |

Total officers | 12 |

| Clerk (for divisional dentalsurgeon) | 1 |

| Technicians (067) | 2 |

| Technicians (855) | 11 |

Total enlisted men | 14 |

With this centralization of control the division dentalsurgeon can utilize personnel to maximum advantage by attaching officersor establishing clinics with units or in locations where the greatest amountof work can be accomplished. Normally five officers should be attachedto forward units to provide emergency treatment and at the same time toaccomplish as much definitive work as possible. These five would nor-mallybe distributed as follows: Each infantry regiment (1), division artillery(1), and engineer battalion (1). The remaining six officers (exclusiveof the division dental surgeon) to be held in service areas where dentalwork can constantly be performed upon rear echelon troops and combat troopsin reserve and in rest areas. These six may be utilized as one large clinicif the situation warrants, divided into two groups of three each, or threegroups of two each. The division laboratory would normally be in conjunctionwith one of these rearward clinics. . . .

The important and fundamental features to be stressedfor a division dental service are: (1) Centralized control; (2) Maximummotorization possible.

Based on these recommendations, new tables of organization and equipmentfor the headquarters and headquarters company, medical battalion, werepublished on 1 June 1945.9 This reorganization concentratedthe entire division dental service in a "division dental section"in the medical battalion, consisting of a division dental surgeon in thegrade of major, a division prosthodontist, and 10 general operators inthe grades of lieutenant or captain.

8Memo, Maj Gen R. H. Mills for Gen F. A. Blesse,8 Feb 45. SG: 444.4.

9T/O&E 8-16, 1 Jun 45.

298

Thirteen enlisted assistants were authorized as follows: 1 sergeant(855) for supply and administration, 10 technicians grade 5 (855) as dentalassistants, 1 technician grade 3 (067) in charge of the laboratory, and1 technician grade 4 (067) as laboratory assistant and truck driver. Thedivision dental section was also authorized a dental laboratory truck;one 2 1/2-ton cargo track with a 1-ton, 2-wheel trailer; six 1/2-ton trucks("jeeps") with 1/2-ton, 2-wheel trailers; a 3-KVA generator;11 Chests No. 60; a field kit for each officer; and enlisted man's kitsfor 11 of the dental technicians. It was provided that "normally 1dental officer (general operator), and 1 technician, dental, (855), willbe at-tached to the following units when in actual combat: each infantryregiment; engineer combat battalion."

World War II ended before the reorganization prescribed in T/O&E8-16 could be put into effect, but previous experience with similar unofficialplans in individual divisions justified the belief that it would resultin more adequate dental service for all personnel of units larger thanregiments.

Even with the new centralized dental service there would undoubtedlybe occasions when dental officers could not function in a professionalcapacity. In an invasion, for instance, dentists could be of most serviceas assistant surgeons during the period when the landing was being consolidated.Under such circumstances there was nothing to prevent the division surgeon,who had the dental detachment at his disposal, from using all or part ofthe dental personnel for nondental duties. But as soon as conditions permitted,the dental detachment could be reassembled to resume its primary functionof preserving the dental health of the command.

DENTAL SERVICE OF A FIELD ARMY

Since the composition of a field army was determined by its missionrather than by fixed tables of organization, the number of dental officersassigned might vary within wide limits-from a minimum of about 100 to amaximum of many hundreds. (The Ninth Army had 650 officers at one time.)10Something less than half of the dentists of an army were assigned to thecomponent divisions operating under the general supervision of divisiondental surgeons. The larger proportion, however, were assigned to hospitalsand army units other than divisions, and the army dental surgeon was directlyresponsible for their activities, as well as for the general guidance ofthe division dental services.

Medical units assigned to an army were concerned primarily with theevacuation and care of casualties, and except for the provision of extremelylimited prosthetic facilities their dentists could not be counted uponto render routine treatment for army personnel. Army medical units variedas widely

10Info furnished by Brig Gen James M. Epperly,former dental surgeon, 9th Army.

299

as did other elements, but a typical allotment (units with dental officersonly) for an army of nine divisions would have been:11

| Units | Numbers | Dental officers |

Medical clearing companies | 9 | 18 |

400-bed evacuation hospital | 9 | 18 |

750-bed evacuation hospital | 1 | 3 |

Auxiliary surgical group (Before April 1944) | 1 | 7 |

Gas treatment battalion | 1 | 3 |

Convalescent hospital | 1 | 4 |

Field hospital | 5 | 15 |

Medical depot company (After March 1944) | 1 | 2 |

| Total | 70 | |

In addition to the dentists assigned to army medical units, a largenumber of dental officers were on duty with the many service and combatelements allotted the command for the reinforcement of the basic infantryand armored divisions. The number of dentists so available was not constant,but generally exceeded the total of all dental officers with the combatdivisions.

The problems of an army dental surgeon were essentially those of a divisiondental surgeon, on a larger scale. However, the difficulties of providingadequate dental care for the organization as a whole were increased inan army, partly because a larger number of troops were involved, but mainlybecause a much larger proportion of the army troops had no regularly assigneddentists. The principle of allotting dental officers directly to individualunits had been based on the assumption that such distribution would providefor the majority of the troops in an area and that the relatively unimportantremainder could be taken care of by means of minor adjustments in the overalldental service. This assumption was partly justified in a division wherethe assignment of 7 dental officers to the 3 infantry regiments and thedivision artillery provided at least minimum dental care for four-fifthsof the total strength of the command. But in an army the situation wasreversed, and dentists assigned to individual army units provided dentalcare for only a very small proportion of the total strength. The natureand magnitude of this problem was more clearly revealed in a study carriedout by the dental surgeon of the Ninth Army in Europe. His analysis ofthe dental service of a "type army" (3 corps of 2 infantry divisionsand 1 armored division each) disclosed the following situation:12

Number of nondivisional troops with a type army | 157,493 |

Number of dental officers assigned to nondivisional troops (including medical units) | 205 |

Average number of troops per dental officer | 768 |

Number of units with assigned dental officers | 141 (23.3%) |

Number of units without dental officers | 463 (76.7%) |

11T/O&E's for the organizations listedvaried somewhat from time to time.

12See footnote 10, p. 298.

300

Number of troops with assigned dental officers | 48,225 (30.6%) |

Number of troops without dental officers | 109,268 (69.4%) |

It will be noted from this summary that the problem of an army dentalsurgeon resulted principally from inequities of distribution rather thanfrom shortages of facilities. The overall ratio of 1 dentist for each 768men was higher than in combat divisions, yet only 48,225 troops were caredfor by their own assigned dentists. The remaining 109,268 had to receivedental attention from officers assigned to other units. In addition tothe usual difficulties of persuading dentists to provide adequate treatmentfor the personnel of other units, the army dental surgeon was thus facedwith the necessity of making, with every important change in the generaltactical situation, new arrangements for the treatment of 100,000 or moremen in 463 units.

The dental surgeon, Ninth Army, also emphasized another fact often overlooked;namely that the dental service of nondivision troops of an army far overshadowedthat of the divisions themselves. There was a strong tendency to regardthe divisions as the "core," of an army and to depreciate theimportance of the "auxiliary" army troops, but the type armyconsidered in the aforementioned summary required only 108 dental officersfor the treatment of division troops while 205 were assigned to army units.Improvements in the Dental Services of divisions, important as they were,failed therefore to solve many of the overall problems of army dental services.

The striking advantages which resulted from concentrating all dentalfacilities of a division into a central detachment under the division dentalsurgeon suggested to some senior dental officers the possibility of applyingthe same principles to the problems of army dental services. Among themore interesting proposals along these lines was a plan submitted by thedental surgeon of the Mediterranean Theater of Operations.13This plan, which was designed to insure greater efficiency and a more equaldistribution of dental service to all military personnel in theaters ofoperations, presented the following changes for eliminating the weaknessesof the system then in effect:

1. Removal of all dental officers from present individualassignments, except for those with hospitals, general dispensaries, andadministrative headquarters.

2. Organization of dental detachments of 15 dental officers,1 Medical Administrative Corps officer, and 24 enlisted assistants andtechnicians. Each detachment to have its own essential transportation andtentage and a mobile dental laboratory. The dental detachment to be organizedand equipped so that it could function as one large clinic or as a numberof smaller installations.

3. Each major force to be authorized dental detachmentsin the ratio of 1 detachment for each 15,000 men. Each detachment wouldbe assigned to an appropriate area and the dental surgeon in charge wouldbe responsible for utilizing his resources in the most efficient mannerfor the benefit of all troops in the area.

13Col Lynn H. Tingay, dental surg, MTO, Suggestedplan for Dental Service in a theator of operations, 15 May 45. SG: 703.

301

During the war no such sweeping reorganization of an army dental servicewas attempted, however, and the coordinating activities of army dentalsurgeons were generally limited to relatively minor shifts of local facilitiesto meet changing situations.

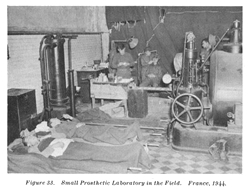

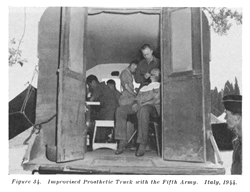

Another persistent problem of the army dental surgeon, especially duringthe first years of the wax, was the provision of an adequate prostheticservice. This was partly solved by the addition to combat divisions ofprosthetic facilities, but it still did not provide the army dental surgeonwith adequate facilities to care for special army troops. Of the army medicalunits, the 400-bed evacuation hospitals and the field hospitals had nolaboratories; the larger evacuation hospitals were often not supplied inarmies; and the convalescent hospitals, limited in number, were usuallyfully occupied with treating their own patients. The army dental surgeonmight thus have only the three prosthetic teams of an auxiliary surgicalgroup and a small number of prosthetic field chests from army medical battalionsand clearing companies to render laboratory service for nondivision troopstotaling more than 150,000 men. Though this situation was greatly improvedby the arrival in quantity of the prosthetic trucks, it was still necessaryto operate improvised (and unauthorized) laboratories in subordinate units(e. g. corps) and in such strategic locations as army replacement depots.

There is evidence in fact that even if the authorized ratio of 1 mobileprosthetic team for each 30,000 men had been attained in World War II,the full laboratory needs of armies and other major units would not havebeen met. From figures on the monthly requirements for replacements inthe Fifth Army and from production records of the prosthetic teams, ColonelLynn H. Tingay, former dental surgeon of the Mediterranean Theater of Operations,calculated that a single team with a division would meet about 75 percentof the prosthetic needs of the (approximately) 15,000 men of that unit.14This left a residue of 25 percent of all prosthetic service for divisionsto be met by other means. On a similar basis, a single truck assigned to30,000 army troops would be able to complete only about 35 percent of allneeded dental prostheses, leaving 65 percent to be constructed by otherinstallations. Colonel Tingay estimated that a "type" army (ninedivisions) would need laboratory facilities for handling about 1,000 casesa month in excess of the combined capacity of the authorized prostheticteams and army hospital laboratories. To meet this situation he recommendedthat "BI" teams ("dental prosthetic detachment, fixed,"with 2 officers and 6 technicians) of the medical service organizationbe authorized for armies in the ratio of 1 team for each 100,000 men. Underfavorable circumstances two or more teams could be grouped to afford theadvantages of "production line" operation. Though it cannot bedetermined without further experimentation whether this or a mobile typeof installation would be more

14Personal Ltr, Col Lynn H. Tingay to author,13 Feb 47.

302

effective in meeting the prosthetic requirements of an army, most dentalsurgeons were agreed that some reinforcement was urgently needed.15

DENTAL SERVICE IN THE COMMUNICATIONS ZONE

The organization of a communication zone varied so widely accordingto the size and geography of the theater, and the nature of the principalmission to be accomplished, that its dental service could have no uniformstructure. In particular, the dental surgeon might he directly responsiblefor all dental activities in the area, or he might act through two or moredental surgeons of subordinate "base commands." In general, however,communications zone dental facilities could be grouped under the followingbroad classifications:

1. Dental officers assigned directly to tactical commands. (In a communicationzone, as in a combat zone, it was difficult to provide a uniform dentalservice with hundreds of individual officers concerned only with theirown units. A detailed discussion of this problem has already been presentedin connection with the dental services of the divisions and armies.)

2. Dental clinics and detachments established in connection with standardtable of organization medical units.

3. Special dental facilities set up to meet unusual. situations. Inthe communications zone auxiliary dental care was provided by a numberof medical organizations. In addition to those discussed in connectionwith an army dental service, the communications zone might have availableany or all of the following, in numbers depending upon the strength ofthe theater:16

Units | Dental personnel | |

| Officer | Enlisted | |

1,000-2,000-bed general hospitals | 5-10 | 9-13 |

25-900-bed station hospitals | 1-4 | 1-7 |

Convalescent centers (3,0000-bed) | 5 | 9 |

Convalescent camps (1,000-bed) | 3 | 6 |

Medical supply depots | 1 | ----- |

Medical dispensaries, aviation | 1 | 1 |

Dental prosthetic detachments, mobile (1 for each 30,000 men) | 1 | 3 |

Dental prosthetic detachments, fixed | 2 | 6 |

Dental operating detachments, mobile (1 for each 25,000 men) | 1 | 1 |

General dispensaries (serving 2,000-10,000 troops) | 1-3 | 2-4 |

Dispensaries (serving 1,500-3,000 troops) | 1 | 1 |

Medical detachments (assigned separate battalions) | 1 | 1 |

Hospital centers (headquarters only) | 1 | ----- |

Maxillofacial detachments | 1 | 1 |

The hospitals provided all types of dental care for their own patients; also treated the more serious oral surgical conditions of troops in nearby units. They had small laboratories and during the first part of the war it was

15(1)Personal interviews by author withsenior dental surgeons. (2) See footnote 3, p. 291.

16The last eight installations listed were part of the MedicalService Organization, T/O&E 8-500, 18 Jan 45.

303

expected that these would provide an important part of the prostheticservice in theaters of operations. It will be pointed out, however, inthe discussion of the overseas prosthetic service, that the demand fordental appliances soon became too large to be met by the hospital laboratories.Planned primarily to care for the sick and wounded, the hospitals did nothave enough reserve capacity to supply dental service for large bodiesof troops.

Of the smaller detachments, the "medical dispensary, aviation,"and the "medical detachment" were assigned to separate bodiesof troops having no regular dental officers, providing a service similarto that furnished by unit dentists. Before hostilities ended dental prostheticdetachments and dental operating detachments were available only in verysmall quantities and were generally used where more critically needed-inthe combat zone. General dispensaries were employed only in connectionwith the more important headquarters, but with only three assigned dentalofficers the amount of dental care provided was woefully inadequate.17The dental officer with a hospital center was engaged in purely administrativeduties. The functioning of the maxillofacial detachment will be discussedin connection with the evacuation of dental casualties. These smaller dentalunits met critical needs but they were specialized organizations designedto meet specific requirements for mobility or to provide care for definitebodies of troops who otherwise would be neglected. Even had they been availablein the numbers authorized, the bulk of the communications zone dental servicewould still have been rendered by unit dentists and hospital clinics.

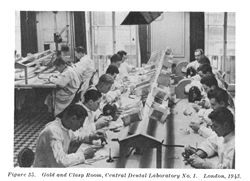

Standard dental facilities sometimes failed completely to meet the needsof large concentrations of troops in the communications zone. The fixedprosthetic team of 2 officers and 6 technicians, for instance, was notdesigned to supply large scale laboratory service for hundreds of thousandsof men, and a 100-man laboratory had to be established in England. Similarly,the largest general dispensary had only 3 dental officers, yet 35 dentistswere required just to care for military personnel in and around Paris.18Large clinics had to be supplied such installations as the replacementdepot near Naples where 5,200 men arrived in one day.19 Consequentlythe communications zone dental surgeon, who was also the theater dentalsurgeon in most instances, was required to improvise a considerable numberof large clinics and laboratories not contemplated in tables of organization.

The theater dental surgeon had no reserve pool of dental personnel withwhich to establish these, essential but nonstandard installations. Dependingupon the urgency of the situation he had possible recourse to two alternatives:

1. If the need for the special facility could be adequately foreseen,the dental surgeon could submit for it a tentative table of organization.If

17See footnote 3, p. 291.

18Ibid.

19Rpt, Peninsular Base Sec, supp. to the Dental History, MTO.HD.

304

approved by the theater commander and the War Department, this tableof organization became the authority for requisitioning necessary personnelfrom the Zone of Interior. The principal defect of this method was thetime element for even under the most favorable circumstances several monthswere required to get the approval of all concerned and to complete theshipment of personnel to the theater. On the other hand, staff officerswere slow to be convinced that a unit not contemplated in existing tableswas actually necessary. The whole process of having a special table oforganization authorized was so cumbersome that only one dental installation,a central dental. laboratory, was so procured in the European theater duringhostilities.

2. The theater dental surgeon might, with the consent of the theatercom- mander, establish the needed installation with personnel already inthe area. This procedure did not increase the total number of officersallotted to the theater, however, and it could be accomplished only by"robbing Peter to pay Paul"; men had to be "borrowed"from other organizations from which they could ill be spared.20Dental surgeons used devious methods to obtain the officers to staff suchfacilities with a minimum of disruption of the dental service. Most ofthe dentists drafted for such duty could be used for only a few weeks andthe turnover of personnel was high. Constant supervision was needed toinsure a steady flow of replacements and to provide qualified officersfor the oral surgical and prosthetic services. Very little organizationfor efficiency was possible when key men might be lost at any time. Personnelfrom the smaller dental detachments were sometimes juggled to provide areasonable approximation of the desired unit. In Europe, for instance,6 fixed prosthetic detachments were used to establish a 36-man laboratoryin Frankfurt.21 Since only 2 of the 12 officers obtained wereneeded in the laboratory the other 10 were used to reinforce the badlyoverworked dental dispensary in the same city. Such subterfuges were countenancedbecause the results justified the means and no one was willing to inquiretoo closely into how they were obtained. The formation of these nonstandard,improvised units was necessary in the absence of any better plan, but thedifficulties encountered emphasized the need for establishing approvedtables of organization for all important installations which may be requiredin an overseas campaign.

Even more than an army dental surgeon, the theater dental surgeon washeavily burdened with the never-ending task of maneuvering minor, widelyscattered, dental facilities to provide care for units with no dental officersand to make available the personnel needed to staff the large nonstandardclinics and laboratories. World War II experience indicated that the problemsof a theater dental surgeon could be materially reduced, and the dentalservice improved, by two steps:

Make available to the theater dental surgeon a small pool of reserveper

20See footnote 3, p. 291.

21Personal knowledge of author who was stationed in Frankfurtat the time.

305

sonnel to meet emergencies and add flexibility to the dental service.The dental surgeon of the European theater stated that "the one recommendationwhich this division cannot stress too strongly is that some provision bemade for a pool of dental officers in theaters of operations."22

Remove dental officers from individual tactical units and assign themto dental detachments of 15 or more dentists, similar to those alreadydiscussed in connection with the dental service of an army. Each dentaldetachment, under an experienced officer, would, regardless of parent organization,be responsible for the care of all troops in its area. Detachments wouldbe allotted throughout the communications zone on the basis of 1 unit forapproximately 15,000 troops and according to the disposition of personneleach detachment would establish a dental laboratory and 1 to 4 or 5 clinics.The theater dental surgeon would make an equitable distribution of thedetachments to meet overall needs but minor local adjustments would bemade on the spot by the detachment commander who would also supervise thedetailed functioning of his men. Such a reorganized dental service wouldhave the following advantages:23

1. The provision of uniform treatment for large and small units wouldbe simplified.

2. Dental officers would function under the immediate observation ofan experienced officer rather than under the loose supervision of a linecommander or a surgeon unfamiliar with the requirements for a good dentalservice. Line commanders would be relieved of the responsibility for thedetailed operation of a highly technical activity having no relation tothe primary mission of the organization.

3. To handle difficult conditions specially qualified men could be provided.

4. Dental officers would be relieved of individual responsibility forsup-plies, records, and other miscellaneous overhead, allowing them todevote more time to their proper duties.

5. Local adjustments of dental service could be made at once, on thespot, without the necessity for prolonged consultations with numerous individualcommanders and dental officers.

It would also appear that the dental surgeon of a major theater wouldbe able to discharge more effectively his responsibility for the qualityof the dental treatment if given the assistance of one or more dental consultants.The

22History of the Dental Division, Hq, ETOUSA,from inception to 1 Sep 44. HD.

23This plan for the organization of the Dental Service has beenproposed by several senior dental officers who occupied positions of responsibilityduring the war, particularly by Maj Gen Thomas L. Smith, Chief of the DentalService, and by Brig Gen James M. Epperly, former dental surgeon, 9th Army,Europe. General Smith, however, has also suggested certain disadvantagesof such a policy. In the invasion of France, purely dental units were givensuch a low priority for shipment that some would not have arrived in lessthan 3 months. It was found that dental installations could be moved toFrance in time to accomplish their mission only if attached to a combatcommand. One laboratory received a warning order for its move several weeksafter it had already set up on the continent subsequent to having beeninformally attached to a line unit for the channel crossing. Applicationof the "cellular" type of dental organization would also necessitatesome revision of plans for dental surveys, but satisfactory alternate schemeshave already been worked out in some divisions and armies.

306

European theater had the services of an oral surgery consultant duringthe war but no full time consultant was on duty in any other theater headquarters.The administrative duties of a theater dental surgeon were sufficient tooccupy most of his time, and in any event it would seem to be expectingtoo much of any one man to ask him to pass on the quality of the care givenby specialists in three or more fields.

DENTAL SERVICE IN AN INVASION

Dental preparations for an invasion began long before the event withan intensified effort to put all men in the best possible condition. Thedental officers of individual units brought surveys up to date, eliminatedconditions which might cause men to become noneffective, and speeded upthe tempo of routine treatment. At the same time dental surgeons of majorcommands reinforced unit dental officers with all available prostheticand operative resources, and a special effort was made to complete essentialreplacements.

With the assembly of the invasion force in the vicinity of the portsof embarkation it was no longer possible to continue dental service ona large scale and emphasis shifted to the care of last minute emergencies.Since by this time the equipment of unit dentists had been packed, thebulk of dental care in the marshalling areas had to be furnished by installationsnot involved in the movement.

In the actual invasion and during the initial assault phase, the activitiesof dental officers differed with the type of action and resistance encounteredbut in general they served as assistant battalion surgeons or performedother nondental duties. In subsequent periods they usually continued insuch capacity until dental equipment could be assembled for the resumptionof normal dental activities. In the meantime, though the incidence of emergencydental cases was low, dental kits were utilized to care for those whichdid occur.

Lag in commencement of dental operations, as such, varied from severaldays to several weeks, and in some combat units fully 50 percent of thedental officers continued to be employed in a medical status for a numberof months. In one such combat unit a dental officer remarked "I gavemore plasma than I inserted fillings."24

The prolonged use of dental officers as auxiliary medical officers waswidely condemned by most senior dental officers, but it cannot be deniedthat due to the exigencies of the first phases of an invasion, dental officersmust be prepared to assume other duties until the situation has becomepartially stabilized. However, experience has shown that unless dentalofficers resume their normal functions at the earliest possible date anyadvantages gained by their emergency assistance will be offset by increasedevacuations for dental reasons.25

24Rpt, 7th Army Sec, supp. to the Dental History,MTO. HD.

25See footnote 5, p. 293.

307

DENTAL SERVICE FOR REDEPLOYING TROOPS

With the end of hostilities in Europe the Dental Service was suddenlycharged with the responsibility for surveying and completing essentialdental treatment for thousands of men being redeployed to other combatareas. Due to the following circumstances this task involved unusual difficulties:

1. Personnel being processed in redeployment centers were availablefor a very short time only, and often arrived in waves which taxed thefacilities provided for normal operation.

2. Redeployment centers were often established in areas where existingdental facilities were limited or nonexistent, so that clinics had to bebuilt, equipment obtained, and personnel assembled before treatment couldbe started.

3. The general reshuffling of officers and men incidental to makingup units for redeployment to the Far East affected dental personnel aswell as combat troops and the confusion of the period multiplied the difficultyof obtaining sufficient dentists and technicians for operation of the necessaryclinics and laboratories. No tables of organization were drawn up for theseinterim installations and personnel had to be borrowed from hospitals orother organizations, usually oil a temporary duty status.

So that he could plan the clinics and supervise their construction orconversion the dental surgeon assigned to a redeployment center usuallyarrived about a week or two before operations were to begin. He then submittedrequisitions for equipment and personally followed their progress throughintermediate offices to insure rapid action. Dental personnel, supplies,and patients usually came in at about the same time. About half of thestaff were obtained from the redeployment center complement and the remainderborrowed from organizations currently being processed. Basic equipmentwas normally the M. D. Chest No. 60 plus such civilian items as could beprocured locally. Lights, cuspidors, and other improvised supplies wereconstructed and installed by engineer or ordnance detachments. Since prosthetictreatment made up a high proportion of all dental care rendered in redeploymentcenters a laboratory was essential, and in the absence of other trainedperson-nel it was often staffed in part by qualified prisoners of war.

At the Florence Redeployment Center,26 which had a maximumcapacity of 25,000 men, provision for a 21-chair clinic was made. A singleoral surgeon was able to handle all extractions but three officers wereplaced on prosthetic duty. One chair was devoted to examinations and onewas used by the x-ray service the remainder for routine operative procedures.The permanent staff numbered 16 officers and 36 enlisted men; the rest.of the personnel required to operate the installations were obtained fromtransient units.

26History, Dental Clinic, Florence RedeploymentCenter, 10 Aug 45, inclosure to Supp. to Dental History, MTO. HD.

308

Dental officers on loan from other organizations had to be replacedat short intervals and dentists of the station complement had to be releasedfor redeployment or return to the United States. Thus the turnover of personnelwas constant and heavy. One of the principal duties of the dental surgeonwas to estimate future requirements for his staff and arrange for necessaryreplacements.

When a unit arrived in a redeployment center the dental surgeon immediatelycontacted the organization commander and arranged for a dental survey ifone was necessary. If the unit had an assigned dental officer he was directedto report to the central clinic for duty as long as he was in the camp.Men in Class I or I-D were called for early treatment, followed by as manyless urgent cases as could be handled in the time available. All urgenttreatment was completed and, except in periods of peak operation, a largeproportion of minor defects were corrected as well, so that a high ratioof the men departing from a redeployment center were in Class IV. Sincefrom 20,000 to 30,000 men might be processed in less than 2 months sucha result could be achieved only with the most efficient organization andsupervision.

The dental condition of men going through the redeployment centers variedwidely according to whether or not they had been in extended combat andwhether or not their units had had assigned dentists. In general, however,dental defects were not excessive. The following comparison of the classificationof men redeployed through a center in Italy and men inducted at Camp Robinson(Arkansas) in 1942 shows that the dental condition of most men had beengreatly improved during their Army service, even while in combat:2728

Class | Redeployment Center Florence | Training Center Camp Robinson |

| Percentage | Percentage | |

| I | 0.9 | ----- |

| I-D | 2.7 | 26.5 |

| II | 19.5 | 29.3 |

| III and IV | 76.9 | 44.2 |

THE EVACUATION OF MAXILLOFACIAL CASUALTIES

Since maxillofacial casualties went immediately into the general chainof evacuation the dental service had no special responsibility for theirmanagement beyond cooperating in their treatment at medical installationsen route. Methods of handling wounded men varied with geography, combatconditions, and transportation facilities, but a typical system might bedescribed as follows:

1. Within a few minutes after receiving his wound the injured man wasusually picked up by a "company aid man" of his own organization.This

27See footnote 26, p. 307.

28Health of the Army, vol. I, Report 1, 31 Jul 46, p. 8.

309

Medical Department soldier was trained in first aid and could stop bleedingor take other steps immediately necessary to save life but his principalfunction was to get the casualty into the hands of a supporting medicalunit which would remove him from the combat area. The aid man stopped hemorrhage,applied a bandage, and directed the wounded man to the battalion aid stationseveral hundred yards to the rear. If the patient could not walk he wascarried by litter bearers sent forward from the same installation.

2. The battalion aid station was set up with field chests in the firstavailable cover behind the "front line." Here the casualty wasseen by a medical officer and possibly a dental officer as well, thoughthe latter was more often located at the regimental aid station. Sincethe battalion aid station had meager facilities and poor protection fromenemy fire the wounded man was held there only long enough to prepare himfor further evacuation and to arrange his transportation to the rear. Hisbandages might be adjusted, he might be given plasma or a sedative if required,and an open airway was assured, but as soon as possible he was turned overto litter bearers sent forward from a collecting station which had beenestablished by medical troops of the division medical battalion. The regimentalaid station was usually bypassed at this point.

3. Division collecting stations were normally established within litter-carrydistance of the battalion aid stations they served and, if possible, ona motor road passable to the rear. Two medical officers were availableand with slightly more elaborate equipment they could attempt emergencyprocedures which were not practical at the battalion aid stations. However,the collecting station was still within easy range of hostile artilleryand mortar fire and its primary mission was the assembly and evacuationof patients rather than treatment. In the absence of a dental officer atthe collecting station the maxillofacial patient usually received onlysuch general care as would minimize the danger of further transportationby ambulance to the clearing station.

4. Clearing stations were division medical installations which werenormally established several miles behind the lines for the further assemblyand treatment of patients from the collecting stations. Four medical officersand at least one dentist were in attendance and equipment included a smalloperating room and ward tents for the temporary care of patients who couldnot immediately be removed to a hospital. A clearing station had to beready to move on short notice, however, and only the most urgent operationalprocedures were undertaken. A maxillofacial injury normally received littlecare at this point beyond the control of bleeding, treatment of shock,and possibly the temporary immobilization of fractured jaws with some typeof bandage. As soon as possible the patient was removed by ambulance toan evacuation hospital.

310

5. Evacuation hospitals of 400 or 750 beds were army installations establishedbeyond the range of ordinary artillery fire and within reach of reliabletransportation to a major hospital in the communications zone. Though theywere mobile and often operated under tentage they were true hospitals andhad the equipment and personnel to institute general definitive treatmentfor casualties who had received emergency care in the installations alreadydiscussed. They possessed medical, surgical, and x-ray facilities, andthe dental officers sometimes, though not always, had prosthetic chestsin addition to the authorized dental operating chests. When casualtieswere heavy a special maxillofacial team might be attached. If such a teamwas available, the maxillofacial injury received conservative debridement,foreign bodies and unattached bone fragments were removed and fracturedjaws immobilized with more permanent fixation than was afforded by bandages.Drainage was provided and prophylactic doses of penicillin or sulfa drugsadministered, if indicated. In the hands of specially trained personnelthis treatment added to the comfort of the patient and minimized disfigurement.In the absence of a maxillofacial team, however, extensive interventionat this point might do more harm than good, and evacuation hospitals werefrequently instructed to limit their maxillofacial treatment under suchcircumstances to conservative measures to prevent infection and the applicationof new bandages and temporary fixation.29

6. As soon as it was safe for a patient with a maxillofacial injuryto leave an evacuation hospital, he was usually transferred by train, plane,ambulance, or ship to a general hospital in the communications zone. Herehe was put in the care of a team which included a plastic surgeon, an oralsurgeon, an anesthetist, and specially trained assistants. His wound wasthoroughly cleaned and nonviable tissue and bone removed; permanent fixationwas applied; drainage was provided and infection, if any, controlled; eventuallythe wound was closed in a way which would best facilitate future plasticrepair. If the injury was not too serious the patient might be retainedat this point until he could be returned to duty. In most instances, however,the severe nature of maxillofacial wounds and the probable need for futureplastic operations made it advisable to return the patient to the Zoneof Interior when he could be transported without danger. Maxillofacialpatients were given a high priority for air evacuation, and in a single5-month period in 1945, 4,907 casualties with head and neck injuries werereturned by air from overseas areas.30

Circumstances often made it necessary to modify the "type"procedure described. In the invasion of a Pacific island, for instance,a wounded man might be taken directly from the beach to a ship having medicalfacilities on board and transported to a general hospital in a rear areawithout passing through any of the installations mentioned. Patients froma battalion aid

29See footnote 10, p. 298.

30Leibowitz, S.: Air evacuation of sick and wounded. Mil. Surgeon99: 7, Jul 1946.

311

station were sometimes taken directly to an evacuation hospital if therewas sufficient cover for ambulances to reach the aid station without beingfired upon, while if there was no cover at all patients might have to betreated in a battalion aid station or a collecting station until nightfallor until the enemy was driven from the immediate area. In general, however,the following cardinal principles were observed: the patient was removedfrom the combat area with all practical speed with only the most urgenttreatment given en route, and definitive care, especially that which involvedremoval of tissue or bone, was delayed until he could be put in the handsof qualified plastic and oral surgeons.

THE MOBILE DENTAL OPERATING TRUCK OVERSEAS31

The need for a mobile operating truck overseas was based on the followinggeneral considerations:

Any practical means of bringing convenient base equipment into the combatzone could be expected to increase materially the efficiency of dentistswith tactical units.

Many small units had no regular dental officers and depended upon itinerantfacilities for their dental care. Officers assigned to such duty requiredequipment which was both efficient in operation and readily transportable,with time lost for packing and unpacking supplies reduced to a minimum.

Requests for mobile operating trucks were received from overseas unitsearly in World War II, but development was exceedingly slow and deliveryin quantity did not start until the spring of 1945.

Since the official model of the operating truck did not arrive overseasuntil shortly before the end of hostilities, reports on its functioningwere meager, though uniformly favorable.32 However, more elaboratereports are available on the many improvised operating trucks placed inoperation before the arrival of the standard vehicle.

In the absence of an official model, almost every theater managed toassemble a considerable number of improvised dental operating trucks ofwidely varying characteristics. In many cases these were built by smallorgan-izations with captured and makeshift equipment, but in Italy theFifth Army went so far as to authorize the construction of dental trailerson standard bodies in the ratio of five trailers for each infantry division.33The following reports are typical of a large number received:

Fifth Army. As in the case of the mobile prosthetic trucks, themobile operating trucks could function under any conditions, and by seekingout the

31For a description of the mobile operatingtruck see chapter V. The history of the development of this item has beentold in Johnson, J. B., and Wilson, G. H.: History of wartime researchand development of medical field equipment. HD.

32Ibid.

33Rpt, 5th Army Sec, supp. to Dental History, MTO. HD.

312

patient saved an inestimable number of man-hours which would otherwisehave been consumed by patients travelling to a point where their needscould be met.34

Twelfth Air Force. In May 1943 it became increasingly evidentthat a great deal of operating efficiency at the chair was being lost dueto the time required to set up and tear down the dental equipment beforeand after an organizational move. At this time efforts were directed towardconstruction of a number of complete dental offices in covered trucks ortrailers which were to remain in operative condition during an overlandmove.

One such unit was constructed at the direction of the surgeon of theTwelfth Air Force in the 809th Engineer Aviation Battalion. At the sametime another mobile unit was being manufactured by ... the 560th SignalAir Warning Battalion. These two units proved so successful in giving dentalattention to outlying stations and facilitating the service as a wholethat coordinated efforts were continued along this line. . . . Throughthe individual efforts of the organization dental officers and with thecooperation of the Ordnance Section of both the Twelfth Air Force and theTwelfth Air Force Service Command, nine mobile dental units were in operation1 February.35

There could be no doubt of the superior convenience of the mobile operatingtruck over the dental facilities available in the M. D. Chest No. 60, andthere was every reason to believe that similar vehicles would henceforthbe considered essential to the dental service overseas and in maneuverareas in the United States. However, in determining the extent to whichmobile units would eventually supplant dental field chests several otherfactors had to be considered. In the first place, the operating truckswere not a substitute for large, conveniently equipped clinics, whereverthe latter were practical. Further, the mobile units cost about $9,000each, while the Chest 60 cost only a little over $300. Obviously it wouldbe necessary to determine whether or not manpower and materials would beavailable for the construction of several thousand operating trucks ina time of national emergency before this item could be adopted as standardequipment for any large proportion of the dentists with the field forces.Also, the mobile units were not adapted for use in jungle areas or on smallPacific islands where a chest which could be carried by hand might actuallybe more mobile than a truck.

It is highly probable that future experimentation with mobile unitswill find means to reduce materially both the cost and the weight of thedental operating truck, possibly by installing lighter equipment in a traileror in a smaller self-propelled vehicle. In 1945 the Director of the DentalDivision recommended further study along these lines.36

34See footnote 33, p. 311.

35Rpt, 12th AF Sec, supp. to Dental History, MTO. HD.

36Final Rpt for ASF, Logistics in World War II. HD.

313

THE PROSTHETIC SERVICE OVERSEAS

World War I

The more rigid physical requirements which were in effect during mostof the First World War prevented the induction of such large numbers ofdental cripples as were accepted for full military duty in World War II.Also, the early end of World War I brought demobilization of the ArmedForces before the full effect of meager overseas prosthetic facilitiescould be felt. As a result, the provision of prosthetic dental appliancesfor the personnel of the American Expeditionary Forces in 1918 and 1919was a comparatively minor problem. Only 13,140 new dentures and repairswere completed in France from July 1917 through May 1919. Of these only2 percent were full dentures.37 Only 1 soldier out of each 150men in the AEF was provided any denture service overseas.

In World War I, laboratory equipment was initially furnished abroadonly in base hospitals, evacuation hospitals, and in certain large clinicsin the principal centers of population. Installations which were calledcentral dental laboratories were established in base sections and depotdivision areas but these laboratories functioned mainly for the camps inwhich they were operating, usually taking impressions as well as completingthe fabrication of cases. No official laboratories were set up specificallyto process appliances from impressions taken within the smaller organizations.No prosthetic facilities were provided in the combat divisions and menin those commands who needed dental replacements had to be sent to a hospitalor to one of the large clinics in the communications zone.

It was soon apparent that there was urgent need for prosthetic equipmentwithin combat units to avoid unnecessary evacuation of personnel. A mansent to a base hospital for construction of dentures might be lost to hisorganization for as long as a man hospitalized with a moderately seriouswound, and the mere fact that a soldier had to leave the combat zone forany type of prosthetic treatment encouraged the willful destruction ofdental appliances and increased the demand for replacements which couldnot be considered essential. The experience of one division dental surgeongraphically illustrates the situation which sometimes arose. This officerwas called to investigate a report that due to absences for constructionof dental appliances the strength of one company of an infantry regimentwas being dangerously reduced. He found that the trouble had started severaldays before when a single officer had been authorized to 90 to Paris forconstruction of a needed replacement. The following day several personswith more or less legitimate requirements had requested the same privilege.On the third day approximately a dozen had reported for this purpose, andon the fourth 20 men, many of whom were merely hopeful, asked

37The Medical Department of the United StatesArmy in the World War. Washington, Government Printing Office, 1927, volII, p. 121.

314

to be sent to Paris. It was necessary to limit further evacuations fromthat company to cases approved by the division dental surgeon.38As a result of such experiences, which were repeated in less exaggeratedform in many divisions of the AEF, a special prosthetic chest weighingabout 200 pounds was assembled and issued to each division as it enteredthe final phase of combat training.39 This chest was used toestablish a laboratory in the division field hospital where it effectuallyprevented the evacuation of troops for dental care. Other changes in theoverseas prosthetic service during World War I were of minor importance.

World War II

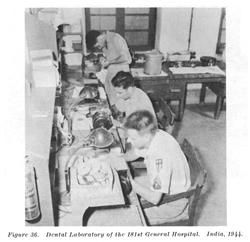

With the experience of World War I in mind the Dental Division was carefulto make what was considered ample provision for prosthetic facilities in.theaters of operations. Tables of organization in effect at the start ofWorld War II authorized dental laboratories in many convenient installationsin the communications zone and as far forward into the combat zone as theycould safely be operated.

In rear areas small permanent laboratories were provided in all generalhospitals and in all station hospitals of more than 50-bed capacity; laterthey were also supplied in convalescent camps and convalescent centers.

Though central dental laboratories were not specifically prescribedfor overseas use, it was anticipated that they could be obtained on specialtables of organization when required.

In the combat zone, fixed or semifixed laboratories were of course impractical,but the portable equipment contained in the M. D. Chests Nos. 61 and 62was provided all convalescent hospitals, evacuation hospitals, and fieldhospitals. Portable laboratory equipment was also carried by the medicalbattalion assigned to each division. The field sets, with their hand-operatedlathes and lack of protection from the elements, were not suitable forlarge scale production but they brought laboratory facilities within easyreach of the fighting man. The Dental Division also expected to obtainmodern laboratory trucks for the use of prosthetic teams in the combatzone,40 and after July 1942 three mobile units were authorized,in theory at least, for each of the auxiliary surgical groups supposedto be assigned to field armies. In spite of these facilities, however,the provision of prosthetic replacements overseas proved to be one of themajor problems of the Dental Service during the first years of the war.

Difficulties in providing adequate prosthetic care overseas resultedmainly from the fact that demands for dental appliances greatly exceededall calcu-

38Personal experience of Maj Gen Thomas L.Smith who was dental surgeon of the 80th Infantry Division, AEF.

39See footnote 37, p. 313.

40Fairbank, L. C.: Prosthetic dental service f or the Army inpeace and war. J. Am. Dent. A. 28: 801, May 1941.

315

lations. In contrast with the total of 13,140 dentures constructed inFrance during the First World War, 845,000 prosthetic cases were completedfor mili tary personnel outside the United States in the 4 years from 1942through 1945; an additional 20,000 appliances were constructed for civiliansand pris oners of war.41 The following prosthetic operationsof various types were completed for each',1,000 men overseas during the3-year period 1943-45:42

| Year | Full dentures | Partial dentures | Repairs | Total |

| 1943 | 10.0 | 28.1 | 19.9 | 58.0 |

| 1944 | 12.3 | 37.9 | 29.4 | 79.6 |

| 1945 | 9.2 | 40.3 | 33.6 | 83.1 |

| Yearly average | 10.5 | 37.2 | 29.6 | 77.4 |

Theater reports in 1944 placed the proportion of overseas personnelwearing dentures at about 10 percent.43 44 45 46

In every area the dental laboratories were pushed to the limit of theircapacity. The Dental Division reported that 7.2 prosthetic operations werecompleted for each 1,000 men overseas in the single month of August 1944.47The Fifth Army in Italy found that 9 men per 1,000 required prosthetictreatment every month.48 The First Army in France reported that"the construc-tion, reconstruction, and repair of dental prosthesesis the main dental problem that we have had to contend with."49A single prosthetic team on a Pacific island (Saipan) constructed 300 denturesa month,50 and on the Anzio beach-head, where 1 dental officerwas killed, 5 wounded, and 1 captured, laboratories in tents protectedby sand bags completed 373 cases under constant shelling and bombing duringMarch 1944:51

The unexpectedly large requirements for prosthetic treatment overseasmay be attributed to a number of factors. Early in the war it was necessaryto ship personnel to foreign areas before essential dental care could becompleted, and these men often needed replacements on arrival in the theater.Many cases were started in the United States but not completed before departureof the patient, and nearly all of the dentures made under these circumstanceswere either lost in shipment or reached the individual after so many monthsthat they were useless. In the rush to get troops ready for duty abroadprosthetic appliances were unavoidably placed too soon after extractionand the dental surgeon of the European theater reported in 1943 that 10percent of

41Data compiled by author from reports in thefiles of the Dental Division, SGO, 1947.

42Ibid.

43ETMD Rpt, SWPA, 6 Jul 44. HD: 350.05.

44Quarterly Rpt of Dental Activities, Hq Base Section No 3,SWPA, 20 Apr 44. HD.

45Medical History 1312th Engineer General Service Regiment,SWPA, May-Jul 1944 (4 Jul 44). HD.

46Quarterly Dental History, Hq Base E, SWPA, 23 Jul 44. HD.

47Memo, Maj Gen R. H. Mills for Technical Div, SGO, 18 Nov 44.SG: 400.34.

48See footnote 33, p. 311.

49Dental History, 1st Army, 18 Oct 43 to 30 Jun 44. HD

50Annual Rpt, 148th GH (Saipan), 1945, p. 24. HD.

51Cowan, E. V. W.: North African Theater. Mil. Surgeon 96: 142,Feb 1945.

316

the men who received prosthetic treatment shortly before shipment wereunable to wear their appliances on arrival in England.52 Thelack of prosthetic facilities in forward units early in the war also encouragedcarelessness in the handling of dentures since loss or willful destructionof an appliance might lead to evacuation from a combat area.

All of these factors were secondary, however, to the simple fact thatan unexpectedly large number of men who required dental appliances hadbeen taken into the Army, thus increasing the demand for both initial andmaintenance treatment far beyond what had been anticipated. Many of thesedental cripples had already been supplied replacements when they arrivedoverseas, but dentures are necessarily fragile and require occasional reconstructionto compensate for gradual changes in the oral structures. Others, borderlinecases, needed appliances after the loss of only one or two additional teeth.The Fifth Army reported:53

It is of interest to note how quickly prosthetic needsappear in newly arrived divisions (85th, 88th, and 91st) even though thesedivisions' troops embarked for overseas duty with all dental requirementsfulfilled. Also of significance is the rate of new dentures and the rateof denture repairs within veteran divisions (1st Armored, 34th, 36th, and45th).

When nearly 500,000 men overseas were wearing one or more dentures itis not surprising that over 800,000 cases were completed during 4 yearsof field operations. Prosthetic requirements overseas, though not as greatas in the large camps receiving recent inductees in the United States,were somewhat greater than for noncombat troops living under relativelystable conditions, but the bulk of the prosthetic treatment rendered overseaswas routine in nature and would have been necessary wherever an equal numberof men had been on duty.

The situation resulting from the unexpected demand for prosthetic serviceoverseas was further complicated by the removal, early in the war, of allportable laboratory equipment from medical battalions and regiments, fromthe 400-bed evacuation hospitals, and the field hospitals. Very littlecorrespondence has been found to explain this important action, and itwas apparently based largely on informal agreements. As nearly as can bedetermined the Army Ground Forces and the Dental Division, the two agenciesmost concerned, were actuated by entirely different motives. The AGF hadstreamlined the division and was anxious to keep noncombatant personneland equipment in the combat zone to a minimum. The Dental Division, onthe other hand, certainly had no intention of leaving the forward areaswithout prosthetic service, but it was equally anxious to substitute laboratorytrucks for the less efficient portable outfits and it appears to have concurredin the proposed action in the belief that the trucks would be able to providean even better service by the time the field chests were removed.54This optimism was later proved premature since

52Personal Ltr, Col William D. White to MajGen R. H. Mills, 22 Oct 43. RD: 703 (ETO).

53See footnote 33, p. 311.

54Memo, Col Rex McK. McDowell for Insp Br, Plans Div, SGO, 15Jan 44. SG: 703.

317

development of the trucks lagged and delivery did not start until thesummer of 1944.

In any event, the Dental Division recommended in November 1942 thatthe field laboratory chests be removed from all medical battalions.55No further correspondence has been found on this recommendation but itis apparent that oral approval was granted and the portable sets were removednot only from the medical battalions but also from the smaller evacuationhospitals. Changes in equipment lists were made very informally at thistime, often by undated pencilled notations; it is therefore not clear exactlywhen the field chests were eliminated, but by 7 September 1943 the DentalDivision noted that "with the exception of the 750-bed evacuationhospitals and the convalescent hospitals the prosthetic service in an armyarea is provided only by the prosthetic teams, of which there are threein the auxiliary surgical group."56