AMEDD Corps History > Medical Specialist > Publication

Part I

THE CONSTITUENT GROUPS BEFORE WORLD WAR II

CHAPTER II

Dietitians Before World War II1

Colonel Katharine E. Manchester, AMSC, USA, and

Major Helen B. Gearin, USA (Ret.)

Section I. World War I and Demobilization (1917-23)

Although the dietitian did not serve with the Army until 1917, the need for her services had long been felt. Well recognized in history is the work of Florence Nightingale during the Crimean War (1854-56). Through her efforts, the entire kitchen departments in Army hospitals in Crimea were systematically remodeled. Diet kitchens were set up in 1855 in Scutari. From these kitchens for the first time, the ill and wounded soldiers were served clean and nourishing food as a part of their medical care.

In two essays on "Taking Food" and "What Food?", Miss Nightingale clearly reflects her insight into the dietary problems of patients:2

Every careful observer of the sick will agree in this that thousands of patients are annually starved in the midst of plenty, from want of attention to the ways which alone make it possible for them to take food. This want of attention is as remarkable in those who urge upon the sick to do what is quite impossible to them, as in the sick themselves who will not make the effort to do what is perfectly possible to them.

* * * * * * *

It has been observed that a small quantity of beef tea added to other articles of nutrition augments their power out of all proportion to the additional amount of solid matter.

The reason why jelly should be innutritious and beef nutritious to the sick, is a secret yet undiscovered, but it clearly shows that careful observation of the sick is the only clue to the best dietary.

Chemistry has as yet afforded little insight into the dieting of [the] sick.

The Medical Department first visualized the necessity for specially trained nurses to assist in feeding the sick during the Spanish-American War in 1898. At that time, the subject of nutrition as applied to a large aggregation of men was not generally understood, but experiments and observations were being made by scientists in an effort to establish a properly balanced and adequate diet for both the ill and well. Dr. Anita Newcombe McGee, giving testimony before a congressional committee in 1898, stated that a considerable number of female nurses had been employed in military hospitals in charge of diet work and that

1Unless otherwise indicated, the primary source of information for this chapter is: Manchester, Katharine E.: History of the Army Dietitian. [Official record.]

2Nightingale, Florence: Notes on Nursing: What It Is, and What It Is Not. [Facsimile of First American Edition Published in 1860 by D. Appleton and Co., New York.] Philadelphia and Montreal: J. B. Lippincott Co., 1946, pp. 36, 41-42.

16

their services were most satisfactory.3 The small number who were employed as "dietists" during the Spanish-American War were retained for only a few years following its close.

When the United States entered World War I, there were no dietitians assigned to Army hospitals. The lack of these specialists was soon keenly felt in many hospitals due to the steadily increasing numbers of war-injured soldiers, the need for conservation of necessary food, and the great number of chronic and convalescent patients requiring diets. In the early months of the war, the American National Red Cross Dietitian Service was called upon to furnish dietitians for base hospitals in the United States and for units going overseas. The National Committee on Dietitian Service of the Red Cross, formed in December 1916 to assist with the enrollment of dietitians, established the first qualifications for dietitians in base hospitals.4 A basic requirement was a 2-year college course in home economics supplemented by at least 4 months` practical experience in the dietetic department of a general hospital. Endorsements were required from the director of the school in which the dietitians received their training and the superintendent of the hospital where they were employed. Dietitians had to be between 25 and 35 years of age. A physical examination by a family physician was also required.

By authority of the Secretary of War, under Executive Order of 11 May 1917, dietitians were appointed by The Surgeon General as civilian employees in the Medical Department at Large for temporary duty for the period of the war emergency. The Civil Service Commission waived the written examination usually required for appointment because of the war. The basic salary of the staff dietitian was $60 per month and of the head dietitian, $65. (See Appendix B, p. 595.) Those going overseas received an additional $10 per month. The dietitians were authorized housing in the nurses` quarters if rooms were available (fig. 3).

By November 1917, the oaths of office of the first 18 dietitians to be assigned to camp hospitals in the United States were forwarded to the Supplies and Accounts Division, Surgeon General`s Office, for approval.5

The distinction of being the first dietitian to serve overseas with a base hospital unit could be claimed by Anne T. Upham of Base Hospital No. 4.

3S. Doc. 221, 56th Congress, 1st Session. Report of the Commission Appointed by the President to Investigate the Conduct of the War Department in the War of 1898. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1900, vol. 7, pp. 3168-3181.

4The American Dietetic Association had not yet been organized so there was no other national professional group to assist with recruitment or the establishment of qualifications.

5The names of these pioneers: Helen Charlotte Aldrich, Bertha Mabel Barber, Mary C. DeGarmo, Nellie Elizabeth Flicker, Anna Bell James, Lola Reid Mace, Josephine L. Perry, Grace Ethel Redmond, Elizabeth C. Hill, Ethel E. Smith, Carol Sykes, Carrie E. Turnbull, Hazel M. Wilson, Lena Wright, Helen McGavy Pond, Ethel Jordon, Marjorie Mercer, and Nancy Elizabeth Kritzer.

17

17

FIGURE 3. Room in nurses` quarters, General Hospital No. 21 (later Fitzsimons General Hospital), Denver, Colo., 1920.

This unit was organized at Lakeside Hospital, Cleveland, Ohio. It sailed from New York on 8 May 1917.

Other dietitians among the first to serve overseas were Marjorie Hulsizer of Base Hospital No. 5, organized at Harvard University, Boston, Mass.; Mary Redford Harold of Base Hospital No. 2, organized at Presbyterian Hospital, New York, N.Y.; Florence Bettman of Base Hospital No. 10, organized at Pennsylvania Hospital, Philadelphia, Pa.; Rachel Watkins of Base Hospital No. 21, organized at Washington University, St. Louis, Mo.; and Mary Lindsley and Margaret Knight of Base Hospital No. 12, organized at Northwestern University, Chicago, Ill. These units sailed between 11 and 24 May 1917 and were the first six base hospitals sent overseas for duty with the British Expeditionary Force.6

Because recruitment of dietitians was slow, Army hospitals in the United States and overseas were supplied with a barely adequate number of dietitians. Those who volunteered did so because of their patriotic desire to serve their country. Assignments were made where the need was greatest.

6The Medical Department of the United States Army in the World War. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1927, vol. II, pp. 20, 630-648.

7Dock, Lavinia L., et al.: History of American Red Cross Nursing. New York: The Macmillan Co., 1922, p. 1425.

18

By Armistice Day, 356 dietitians had been assigned to military hospitals, 84 overseas and 272 in the United States.7

From the earliest months of the war, Miss Dora E. Thompson, Superintendent of the Army Nurse Corps, had felt the need for a supervising dietitian to care for the activities of dietetic service in the Surgeon General`s Office. It took months to resolve the technicalities concerning the appointment of a civilian to that position. Miss Lenna F. Cooper (fig. 4), Director, School of Home Economics, Battle Creek College, Battle Creek, Mich., was appointed to this position by the Civil Service Commission upon the recommendation of The Surgeon General. She took her oath of office on 11 November 1918, Armistice Day, a little late to bring much in the way of aid and encouragement to dietitians in the service during the war. Miss Cooper was assigned to the Office of the Superintendent of the Army Nurse Corps, because her work was so closely allied to that of Miss Thompson. Her duties included general supervision of the work of all dietitians--recruiting, assignment, transfer, discipline--and the inspection of Army hospital dietary departments. Miss Cooper`s leave of absence from Battle Creek College could not be extended and she relinquished her position in the Surgeon General`s Office on 7 August 1919. Miss Josephine Happer was Miss Cooper`s replacement. She was assigned to Walter Reed General Hospital, Washington, D.C., and remained acting supervisor of dietitians until January 1920.

Many misunderstandings arose concerning the status of dietitians going overseas. On 2 October 1917, the Red Cross issued a circular letter to all base hospitals being activated stating that when a dietitian was not a nurse she would come under the heading of a "civilian employee and should be included in the civilian list." Each chief nurse was instructed to communicate with the medical director of the base hospital in order to reserve a vacancy for the dietitian from the civilian positions authorized because otherwise no salary or transportation could be secured. The dietitian as a civilian employee was not charged against the overall authorization of nurses.

Perhaps the reason that dietitians accomplished as much as they did was because they were in a sense undisciplined. Their training had given them fundamental knowledge of their subject matter together with a genuine desire to put this to practical use. Since they were not oriented to the discipline of either the soldier or nurse they worked on their own initiative, little troubled by precedent, proceeding as fast and as far as the commanding officer or mess officer would permit. Surely, whatever success the dietitians had to their credit in the early part of the war was because once given the opportunity, they were able, in most instances, to demonstrate their value to the service.

19

19

FIGURE 4. A contrast in uniforms. At the annual meeting of the American Dietetic Association in 1942, Miss Lenna F. Cooper (right), supervisor of Army dietitians in 1918, models her uniform for Miss Helen C. Burns, supervisor in World War II.

20

Since there were no regulations published for dietitians before May 1918, the duties of dietitians were not standardized. Overseas, their duties varied from taking care of the nurses` home and giving occasional assistance to the officers` mess to planning and serving diets to patients. In some instances, the dietitians themselves prepared food for the very sick patients or had charge of the general hospital diet kitchen. During the early months of the war, few dietitians were given an opportunity to plan menus and supervise the preparation of regular diet food in the patients` kitchen.

Miss Upham, assigned to Base Hospital No. 4 which had been loaned to the British Government, found that there was little concept among the British of what a dietitian was supposed to do. At first, Miss Upham supervised the nurses` mess hall and performed housekeeping duties in the nurses` quarters instead of working in the hospital kitchen. She explained this by saying, "I was in a British hospital where there never had been a dietitian; consequently, I had to prove to the British officials that we could be of service." Evidently her sense of humor carried her through many disheartening experiences. On one occasion, a British commanding officer, reading the roster of the unit, saw the word dietitian after her name. He asked, "What kind of a creature is that?" At first, the general opinion prevailed that she knew only how to serve "ice cream and dainty foods." She was later introduced to a British official as "our lady cook." However, by June 1918, her capabilities were recognized and she was given complete charge of the planning, preparation, and service of food to all patients, in addition to supervising the special diets and the officer patients` diets.

The first authority that outlined the duties of the dietitian overseas and established her status as a civilian employee was published in May 1918. 8 The commanding officers were urged "to use their [the dietitians`] expert knowledge for the correction of * * * monotonous and ill-balanced dietary, poor service, and lack of cleanliness in the kitchen and the kitchen personnel," and to exercise the constant vigilance and attention to details to successfully administer the mess.

Miss Mary Pascoe who was assigned successively to Base Hospitals Nos. 8, 117, and 214 illustrated the inconsistencies of this circular when she stated that "The net result of all this was practically nil. For how could the dietitian supervise, lacking authority to give orders? She could use wile and guile, persuading the mess sergeant to carry out her wishes--an energy wrecking, energy dissipating procedure; or she could finally seclude herself in some niche and cook. Only thus could she be assured that at least the `light diets` would be edible."

Miss Cooper, during her tour as supervising dietitian in the Surgeon General`s Office, inspected the dietary departments of 30 Army hospitals in the United States. Realizing from these inspections that there was an overlap of the responsibilities of the mess officer and the dietitian, she

8American Expeditionary Forces Circular No. 27, 13 May 1918.

9Circular Letter No. 131, Office of The Surgeon General, 8 Mar. 1919.

21

worked hard to obtain standardization of the dietitians` duties. In March 1919, a circular letter9 was published which defined the duties and status of dietitians in military hospitals and made her responsible for her professional work to the commanding officer of the hospital. As an assistant to the mess officer she was to cooperate with him and the chief nurse. It pointed out that even though the dietitian was a civilian employee of the Medical Department she was not to be classified with cooks and maids for "to place a competent dietitian on the same basis with cooks and maids is an injustice to her and a disadvantage to the hospital in which she is working."

Despite all the handicaps that befell the dietitians in World War I, the services rendered justified their existence as a part of the Medical Department. The work of the dietitian was remarked upon by a member of the American Expeditionary Forces. Miss Mary Hungate, dietitian, Base Hospital No. 51, on returning to the United States, met a brigadier general who did much to hearten the dietitians by personally thanking them for their good work. From previous experiences in Army hospitals, the general recalled that the food was unfit for the sick. However, when he became a patient in an American Expeditionary Forces hospital, he found the food much improved. Upon inquiry, he learned that a trained dietitian was responsible.

Another tribute paid to the dietitians in World War I came from Maj. Roy G. Hoskins, MC, Division of Food Nutrition, Surgeon General`s Office, who visited nearly every camp and cantonment hospital in the United States. Major Hoskins said, "When the dietitians first came into the Army, they encountered many difficulties incident to the introduction of women into what had previously been in the military experience a strictly masculine pursuit. I have much admiration for the skill with which they met these difficulties, and the valuable service they rendered to the Army." Likewise, the annual report of The Surgeon General to the Secretary of War in 1919 recognized the value of food and nutrition for both the sick and well.

The increasing demand by hospitals for additional personnel and the complimentary verbal reports from commanding officers were evidence of the popularity of dietitians. One interesting assignment in other than hospital food service was that of the dietitian who was assigned in 1919 to Rockwell Field, San Diego, Calif., to work on the diet of flyers.10

In addition to the struggle for status and authority as civilians in an established military organization, the dietitians were required to work with limited food supplies, untrained personnel, and a shortage of equipment. Effective on 26 May 1918, the ration allowance of 50 cents a day per patient was approved by the Secretary of War. The value of the ration was

10Annual Report, Supervising Dietitian (Miss Lenna F. Cooper), Medical Department, U.S. Army, to The Surgeon General, 7 July 1919.

22

60 cents11 for Army hospitals overseas and for hospitals in the United States with tuberculous patients.

The ration issued to base hospital units varied in different areas. In England, U.S. Army hospitals were authorized to draw the special troop ration for enlisted personnel and civilian employees and any part of the ration desired for nurses and patients. They could supplement this allowance by local purchases with the exception of meat and sugar which could not be bought in excess of the ration allowance.12 From the accounts of dietitians who served overseas in World War I, it was evident that food was an uncertain commodity. Hospitals which were on a direct railroad to the frontline had food supplies sent on the ammunition trains. If the track ahead was clear, they would go by the hospital without stopping to unload the food. In addition to the difficulties of transportation of food, there was little in the ration that was suitable for the desperately ill and wounded men. Butter in 5-pound cans was rancid and inedible. Fresh milk was not available, and eggs when available cost from $1.25 to $3.00 a dozen. Canned goods were of poor quality, and canned vegetables usually consisted of corn, peas, tomatoes, and more tomatoes.

Miss Pascoe, on returning from France in 1919, was asked to speak before the New York Association of Dietitians. She mentioned the quantity of tomatoes in the rations, closing with a vocal outburst against a "scheme of life that had almost drowned me in tomatoes." She was ashamed and humiliated when a lady in the back of the room chided her by saying that tomatoes were valuable because of their vitamin C. During her service overseas, Miss Pascoe had not had an opportunity to learn of the discovery of vitamin C.13

Ordinary foods such as gelatin, junket, cocoa, broth, and other items required for light and special diets were totally absent. Flour, sugar, canned and powdered milk, and dried turnips were plentiful. Bacon and prunes were received in varied amounts from time to time. Frozen beef, a scarce item, had to be cooked upon thawing because of lack of refrigeration. The dietitians developed recipes in an attempt to disguise the identity of some foods which they received in quantities such as canned salmon, corned beef, and so forth.

During the war, there was a shortage of experienced cooks especially in the hospitals. Cooks and kitchen police for the hospital kitchens came from every possible source. Miss Hungate wrote that she "had never seen a more cosmopolitan gathering than the kitchen force in Base Hospital No. 51. Beside the student from Colgate, who had enlisted in the hospital corps in order to drive an ambulance, sat an ex-acrobat from Ringling`s [Ringling Brothers Circus]. The cooks who occupied the seats of honor included one handsome Italian, one East Side Jew,

11A ration is food for the subsistence of one person for 1 day.

12The Medical Department of the United States Army in the World War. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1926, vol. VI, p. 693.

13Mrs. Mary P. Huddleson (formerly Mary Pascoe) as editor of the Journal of the American Dietetic Association during World War II included mention of all research and investigation in the Journal for the information of dietitians serving in World War II.

23

a Virginia Negro, and an Anglo-Saxon who had formerly labored in a Kentucky brewery. In addition, there were three German prisoners of war, one Russian, a little homeless waif adopted after his daily pilfering of our garbage cans, and three volatile chattering French women."

All during the war, ambulatory patients worked in the hospital messes. Mrs. Caroline B. King reported that the convalescent soldiers made excellent cooks. Many dietitians had recollections of the erratic cooks and the shell shocked personnel who ducked under the nearest table if a pan clattered to the floor.

In August 1919, Miss Pascoe reported to Miss Cooper that better training for Army cooks in health, food preparation, sanitation, and economy was needed in all the Army hospitals. Of the many cooks who served with her in hospitals in France only two had had previous training or experience as cooks either in the Army or civilian life. Miss Pascoe`s best mess sergeant had starred on the New York stage. Of her diet kitchen staff, one was a Metropolitan Opera singer, another a big league ball player, and another a man worth $20 million.

Army hospitals in the United States were equally short of qualified mess personnel. Miss Mary Foley, dietitian at Fort Riley Base Hospital, Kans., mentioned that diet cooks assigned to each kitchen under the supervision of the dietitian were often inexperienced as well as disinterested in their work. Quite often the diet cook assigned was a kitchen police who had done unsatisfactory work in the mess hall. Because of the shortage of help and the lack of skills of the supervisors, the dietitians were placed in charge of two mess halls and kitchens of the hospital as an experiment to improve food service. The dietitians were in charge of the preparation of food for all patients. This gave them an opportunity to teach the cooks how to prepare food for approximately 20 different types of diets which resulted in a greater variety of food for the patients. At the end of 2 months, an official inspector from the Surgeon General`s Office commended the commanding officer of the hospital on the two sections supervised by the dietitians as the cleanest and best organized of any Army hospital in the United States. In addition to their regular duties, the dietitians conducted classes in dietetics14 and cooking 2 nights a week for the mess sergeants, cooks, and kitchen police.

The dietitians overseas and in the United States had to improvise much of the mess equipment used in Army hospitals. Only certain items of equipment were authorized for issue with the No. 5 Army range for use in base and evacuation hospitals overseas. With this limited equipment, it was evident that many additional items were needed.

Mrs. King, on arriving in France, prepared the first meal out-of-doors on field ranges sunk in yellow mud. The wind eventually blew the stovepipes across the field, and rain put out the fires. The new hospital, when completed, was a conglomeration of huts and tents in the open

14The Army Hospital Dietitian in World War I. J. Am. Dietet. A. 20: 398, June 1944.

24

field. When the diet kitchen was built, it consisted of 12 wood-burning ranges, 4 sinks, and several huge tables that the corpsmen had manufactured from rough lumber. It was evident from the letters reviewed in the record that the tent kitchens had little or no equipment. Bottles were used for rolling pins, new GI garbage cans for mixing bowls, and small fenceposts for mashing potatoes.

Miss Knight, of Base Hospital No. 12, worked in a tent mess hall seating 320 persons, 8 at a table. Serving was done cafeteria style, and all food was carried across an open road from the cookhouse. An improvised dish warmer had been built. It was a huge box lined with pieces of tin from flattened cracker boxes. The shelves were of woven wire fencing and heat was furnished by a little oil stove on the bottom shelf. Dishwashing was done out-of-doors. Only a canvas stretched over tent poles protected the dishwashers. It took six army stoves, each with a huge pot, to supply hot water for dishwashing. Sometimes 1,450 persons were served each meal in this tent mes shall, which meant that dishes had to be continually washed during the serving period.

The first reference concerning the use of food carts in Army hospitals was found in a memorandum from Lt. Col. John R. Murlin, SC, to Col. Deanne C. Howard, MC, Surgeon General`s Office, dated 19 February 1919. He stated that the best food cart of which he had any knowledge from various inspections of hospitals was the one devised by Lt. Col. William R. Dear, MC, at Camp Lee, Va. To quote, "This cart, built on the fireless cooker principle, kept the food thoroughly hot. It was mounted on large wheels and was provided with springs so that there was no slopping of food along the corridors."

From 1917 to 1920, hospital commanders of various hospitals in the United States made requests to The Surgeon General for new items of food service equipment, such as food carts, meat choppers, aluminum pans and dishes, cake mixers and dough mixers, butter cutting machines, steel dishwashing machines, electric potato peelers, electric cookers, electric stoves, portable ranges for diet kitchens, and 40-gallon steam-jacketed kettles. Because of war shortages and limitations, many of these items could not be supplied.

As a civilian employee, the dietitian in World War I was not entitled to wear the uniform issued to the Army Nurse Corps. By necessity, she was required to wear whatever uniform was available. This was particularly true of the dietitians serving overseas, inasmuch as there was no source of uniforms upon which they could draw when any item of clothing became too worn to wear. Mrs. King, in 1918, noted that her oversea uniform consisted of two chambray dresses and one slate blue suit. It wasn`t long before they became faded and her mess officer complained to the commanding officer, "If you don`t give my dietitian another uniform, I`m going to wrap her in an American flag!"

25

25

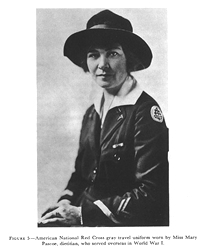

FIGURE 5. American National Red Cross gray travel uniform worn by Miss Mary Pascoe, dietitian, who served overseas in World War I.

On 15 August 1917, the Surgeon General`s Office published specifications for uniforms.15 The indoor uniform for dietitians would consist of a white, one-piece dress, a rolled white collar, white cap, and a caduceus with the letter "D" on it. For foreign service, the outdoor uniform was a blue cotton-crepe dress, when white was impracticable, a white cap, and insignia. The outdoor uniform included an Oxford gray Norfolk suit, an overcoat, a black velour hat for winter, a black or white straw sailor hat for summer, gray gloves, black or white shoes, a white or gray waist, and a black ribbon tie and a plain bar pin. On the

15Special Regulations 41, Office of The Surgeon General, 15 Aug. 1917.

26

lapels of the suit and on the collar of the overcoat, the insignia and the letters "U.S." were worn.

According to a circular letter issued by the Red Cross on 2 October 1917, a gray worsted dress, cape, ulster, and black velour hat were provided for the dietitians. By April 1918, the uniform situation had been restudied. The white uniform was made like the nurses` uniform. The Red Cross cape could be worn if the dietitian was enrolled in the Red Cross. A gray travel uniform (fig. 5) made in the same style as the Army nurses` uniform was to be purchased after assignment to duty. The dietitian was proud to be entitled to wear the Red Cross Dietitians` Badge, if she was enrolled under the Red Cross, and to be permitted to wear the letters "U.S." and the caduceus with the letter "D," when available.

Miss Hungate, in recounting her experiences overseas, wrote of her embarkation at New York as follows: "The hundred nurses all wore street uniforms of blue serge, blue velour hats and tan shoes, while I, the Dietitian, the hundred and oneth, was duly fitted out in a similar suit of gray, a black hat and black shoes. There was no question about it, I was the odd member of the family * * *, we scurried in through a coal-hole down in the bowels of the ship, and I, with my gray suit and black hat, trailed in the rear as pleased as Punch over being allowed to go along, even though no one, myself included, had any definite ideas about just what I was going to do."

The Army`s urgent need for qualified dietitians was well known to Miss Cooper long before her assignment to the Surgeon General`s Office because of the work she had done with the Red Cross Committee on Dietitian Service. As director of a school of home economics, she realized that students could be more adequately prepared to work in Army hospitals if special training were given and emphasis placed on the food service procedures of the Army. After collaboration with the dietitian at Camp Custer Base Hospital, Mich., she planned a special 4-month training course for those of her students who were interested in working in Army hospitals. Field trips were made by the students to the Base Hospital to observe the Army methods.

However, realizing the immediate need for large numbers of dietitians with Army training, Miss Cooper conceived the idea of sending capable students from the Battle Creek Sanitarium to the Base Hospital, for practical training. She wrote to Lt. Col. Ernest E. Irons, MC, Commanding Officer, Camp Custer Base Hospital, as follows: "It has occurred to me that there would be no better place for training these dietitians for Army work than in an Army hospital. Would it be possible for you to allow us to send to you some of the best students for training as student dietitians?" The Surgeon General approved this training course for pupil dietitians and requested that 2 weeks prior to the com-

27

pletion of the 4-month course a report of the efficiency of these dietitians be forwarded to his office with a recommendation as to the advisability of appointing them as dietitians.

The 4-month course for pupil dietitians at Camp Custer Base Hospital was quite comprehensive in scope. The first month was spent doing administrative work, such as distributing menus to wards, receiving and checking diet cards and supply slips, totaling diets for cooks, keeping accounts, and maintaining records of the various diets. By observing in various kitchens and wards, they became acquainted with food service, tray service, garbage inspection, and dish sterilization. During the first month, they also observed in the commissary the Army system of buying, ordering, and issuing food. The second month, the pupil dietitians were assigned to the patients` kitchen where they planned menus, calculated caloric values of three meals each week, ordered supplies for regular and light diets, and supervised preparation of food for patients including special diets. During the last 2 months, the pupil dietitians took charge of the nurses` kitchen and acted as diet supervisors on the ward.

The four pupil dietitians at Camp Custer Base Hospital, who entered on duty between 15 October and 1 November 1918, completed training in February 1919. This was the first training program on record for dietitians in Army hospitals, and even though it was too late to be of much help in World War I, it is significant because it was the forerunner of the Army training courses for dietitians.

Before her resignation in 1919, Miss Cooper recommended to The Surgeon General that a training school for Army dietitians be established at Walter Reed General Hospital. There, qualified dietitians would be under observation and instruction as to the special features of the Army and work for a period of time before being sent to other posts where they would probably be the only dietitians. A training course, however, was not established until 1922. (See Appendix C, p. 597.)

Dietitians returning from overseas for demobilization were given a cursory physical examination for any gross evidence of contagious disease. Even though the dietitians had been exposed to the hazards of war and had incurred disabilities resulting from service under arduous war conditions, they were not eligible for the hospitalization privileges which were available to military personnel. More than one dietitian physically disabled as a result of her service with the Army was given assistance in hospitalization by the Red Cross.

Most of the dietitians returned to civilian positions as soon as possible after demobilization. Final discharge papers were forwarded from the Surgeon General`s Office at the expiration of accrued leave, and discharge was made with the approval of the Secretary of War.

28

Four dietitians, Florence Bettman, Margaret Knight, Anne T. Upham, and Rachel Watkins, gained considerable recognition when they were cited in 1919 by the British Government "In recognition of meritorious services rendered the allied cause."

In addition, Marjorie Hulsizer was decorated by King George V of England as well as by the French Government. Miss Hulsizer in introducing the comparatively new profession of dietetics into the British Army was called "home sister" in contrast to the British Army nurses` title "nursing sister." A memorial award given by the American Dietetic Association was established in 1945 to perpetuate the memory of Marjorie Hulsizer Copher in recognition of her distinguished service to the dietetic profession. The first recipient of this award was 1st Lt. Ruby F. Motley, Medical Department dietitian, released prisoner of war of the Japanese in World War II.16

Records indicate that four dietitians died while on duty with the Army in World War I. The two dietitians who died while serving in cantonment hospitals in this country were Miss Olive Norcross of Worcester, Mass., at Camp Dix, N.J., on 26 September 1918, and Miss Mada Morse of Foxboro, Mass., at Camp Taylor, Ky., on 24 September 1918. The two dietitians who died while serving overseas were Cara Mea Keech, Base Hospital No. 68, 18 October 1918, and Marion Helen Peck, Base Hospital No. 44, 17 February 1919. Miss Keech was buried in England and Miss Peck was buried in Suresnes, France.

In July 1919, The Surgeon General orally requested that Miss Cooper, Supervising Dietitian, submit recommendations on the future position of the dietitian in Army hospitals. (See Appendix A, p. 593.) Subsequent history proves that most of the recommendations made by Miss Cooper to improve the status of dietitians after World War I were adopted during World War II. She stated that there was a need for dietitians on the permanent staff of the larger Army hospitals, as in civilian institutions. In view of the many letters received from dietitians expressing disappointment and a feeling of unfairness in not receiving the same privileges as granted to nurses, Miss Cooper recommended that all "female civilian employees of the Medical Department in the field receiving their appointment from the Secretary of War (in other words, technically trained women) should be granted the same privileges as are granted the members of the Army Nurse Corps." To accomplish this she recommended the establishment of a separate corps

16The First Marjorie Hulsizer Copher Memorial Award. J. Am. Dietet. A. 21: 703-704, December 1945.

29

for dietitians with a competent dietitian as director in the Surgeon General`s Office. The director was to "be put on the regular list of inspectors of the Hospital Division, to be called upon to make inspection where the mess is involved." Miss Cooper thought that dietitians belonging to this corps and assigned in the field should be responsible professionally to the commanding officer. Despite all the handicaps that confronted the dietitian in World War I, she believed that the contribution they had made to improve patient care proved their qualification to be a permanent part of the Medical Department.

Section II. Peacetime (1923-40)

Although the experiences of World War I were disheartening to many dietitians, their services had brought into vivid reality the need for qualified dietitians in Army hospitals. By 1931, the American College of Surgeons required that a qualified dietitian be employed on the staff of a hospital before approval by that organization could be obtained. The educational and professional qualifications established by the Surgeon General`s Office required that an applicant have a 4-year college course with a degree in foods and nutrition plus an 8- to 12-month course in a recognized school for hospital dietitians.

In 1937, in addition to a bachelor`s degree from an accredited college or university with a major in food and nutrition or institution management, graduation from an approved 12-month training course was required. Throughout the peacetime period, the qualifications for dietitians met the requirements established by the American Dietetic Association. Applicants had to meet the Army physical qualification standards. The basic salaries (Appendix B, p. 595) for civilian dietitians ranged from $840 per annum in 1923 to $1,820 in 1942, and were paid from various funds: the Medical and Hospital Department, Army; the Civilian Conservation Corps; or the Veterans` Bureau (now Veterans` Administration).

During the peacetime period, three dietitians, Miss Genevieve Field (1922-25), Miss Grace H. Hunter (1925-33), and Miss (later Lt. Col.) Helen C. Burns17 (1933-42), in addition to being the chief dietitian at Walter Reed General Hospital, were also responsible for the administration of the training course. They maintained liaison with The Surgeon General on all dietitian activities both in professional and personnel areas. The improvement of the status of the Army dietitian during peacetime years and the high standard of the training course for hospital dietitians at Walter Reed General Hospital were largely due to the planning, supervision, and recommendations of these dietitians.

The training program was initiated at Walter Reed General Hos-

17Later Maj. Helen B. Gearin, WMSC.

30

pital, 2 October 1922, as part of the Medical Department Professional Service Schools at the Army Medical Center. The course was organized under the direction of Brig. Gen. James D. Glennan, Commanding General, Army Medical Center (later Walter Reed Army Medical Center), Washington, D.C., and Miss Field who was assigned there during World War I. This was the only training course for dietitians conducted by the Army from 1922 to 1942. The program always met the requirements of the American Dietetic Association. As of August 1942, approximately 210 dietitians had been graduated from this course. (See Appendix C, p. 597.)

Dietitians were assigned to Army hospitals at the request of the commanding officer of the hospital. Upon resignation or transfer of a dietitian, the commanding officer communicated with The Surgeon General and stated whether or not a replacement was desired. The dietitians were normally graduates of the training course for hospital dietitians at Walter Reed General Hospital.

The Surgeon General`s Office also sent letters to commanding officers of the various hospitals stating the date that a class of dietitians would complete training at Walter Reed General Hospital. This facilitated the placement of these graduates and aided in filling vacancies more promptly.

Even though The Surgeon General strongly recommended that Army hospitals employ only those dietitians who had training at Walter Reed General Hospital, in a few cases where serious shortages existed it was deemed necessary for commanding officers to employ civilian trained dietitians provided they met the qualifications established by The Surgeon General. The Surgeon General approved these appointments only as an emergency measure such as in the case of Miss (later Maj.) Ruth Boyd employed at Letterman General Hospital, San Francisco, Calif., in 1936.

Recommendations for promotions were made through the commanding officer of each hospital to The Surgeon General. The Surgeon General, by authority of the Secretary of War, then approved the promotion. Resignations were submitted to the commanding officer of the hospital by the dietitian. The commanding officer approved the resignation and submitted it to The Surgeon General with request for replacement if one was desired. The Surgeon General, in turn, approved the resignation and issued a final order for discharge.

The number of dietitians on duty in Army hospitals gradually increased during the peacetime years from 24 in 1923 to 53 in 1939. One drastic cutback in strength occurred in 1933 as a result of the National Economy Act. In the 3-month period from March to June, 28

31

31

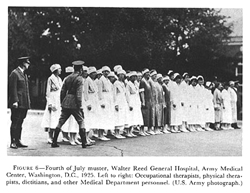

FIGURE 6. Fourth of July muster, Walter Reed General Hospital, Army Medical Center, Washington, D.C., 1925. Left to right: Occupational therapists, physical therapists, dietitians, and other Medical Department personnel. (U.S. Army photograph.)

dietitians were released, leaving only 7 dietitians serving with the Medical Department. By 1934, a majority of the dietitians had been reemployed by the Army.

The value of having this number of highly qualified dietitians was soon evident. The knowledge and experience which these dietitians had gained in their years of service in Army hospitals enabled them to assume positions of responsibility and leadership during the period of rapid expansion for World War II.

During the early peacetime period, it is believed that the on-duty uniforms worn by dietitians in Army hospitals were much like the white uniforms worn by the dietitians in World War I. In order to distinguish the dietitians from nurses, General Glennan recommended to The Surgeon General that dietitians be authorized to wear one blue ribbon on their caps, the same shade of blue used in the lining of the cape issued to dietitians by the Red Cross in World War I. The Surgeon General, in August 1922, authorized the wearing of a band of blue ribbon no wider than one-half inch on the dietitian`s cap.

In 1925, The Surgeon General described the dietitians` uniform as a straight one-piece dress of white poplin or percale (fig. 6). A small white cap of Indian linen was worn. An Oxford gray cape lined with blue flannel completed the uniform. Later, the cap was changed to

32

32

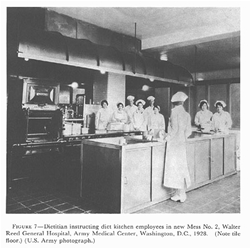

FIGURE 7. Dietitian instructing diet kitchen employees in new Mess No. 2, Walter Reed General Hospital, Army Medical Center, Washington, D.C., 1928. (Note tile floor.) (U.S. Army photograph.)

white lawn; the head dietitian was authorized to wear one band of blue velvet ribbon one-half inch in width on the cap, and the graduate dietitian, one band of blue velvet, three-eighths of an inch.

The dietitians assigned to Army hospitals after World War I were confronted with many of the problems that existed prior to the signing of the armistice. Dietitians were still civilians employed in a military organization working under a mess officer of the Medical Administrative Corps. Their duties in some hospitals were of such scope that they carried great responsibility, and in other hospitals, they were assigned only the supervision of the preparation and service of special diets.

The scope of the Army dietitian`s work and the responsibility she was given were dependent to a large extent upon the person to whom she reported directly and to the hospital commander. Dietitians were allowed more and more responsibility in patient feeding in Army hospitals

33

as the science of nutrition progressed and the place of diet in the prevention and treatment of disease was recognized. Dietitians were assigned to certain medical wards to assist with the metabolic treatment of the patient. In the larger Army hospitals, dietitians supervised the main mess as well as the diet kitchen (fig. 7). They also contacted regular and modified diet bed patients on the wards in order to insure good dietary care. In addition, their duties included teaching courses for patients with diabetes as well as others on modified diets.

An indication that dietetics was becoming more and more important in Army hospitals was evidenced by the appointment of a Medical Corps officer to the position of Director, Dietetic Department, Walter Reed General Hospital, on 1 November 1929. Maj. (later Col.) A. L. Parsons, MC, the first medical officer to fill this position, had two assistants, one, an officer of the Medical Administrative Corps, and the other, the chief dietitian. Because of the training course for dietitians, Walter Reed General Hospital was the only Army hospital authorized the position of chief dietitian. Dietitians in charge at other hospitals were known as head dietitians.

An article in the Journal of the American Dietetic Association in 1930 described in detail the duties of administrative dietitians, scientific (therapeutic) dietitians, and teaching dietitians at Walter Reed General Hospital.

The administrative dietitian, assigned to the hospital mess, was required to have knowledge of food supplies, cost and marketing conditions, buying, receiving, checking, storing, and distribution of food. She was responsible for the planning of balanced menus, preparing orders for all foods, and supervising the preparation and cooking of foods. She arranged the duties of the employees and had supervision of their work. She checked the amount of food and food supplies sent to the wards and made ward rounds to confer with doctors, nurses, and patients. The supervision of the serving of food in the mess hall, dining rooms, and wards was part of her responsibility. It was pointed out that this dietitian had a great deal of influence in controlling the food budget of the hospital which had to be regulated to effect every possible economy and still maintain a high standard of efficiency.

The scientific (therapeutic) dietitian was in charge of special diets. In addition to patients with diabetes, many other conditions and diseases called for scientific management by the dietitian. Experimentation was done with the ketogenic diet for patients with epilepsy. Walter Reed General Hospital at this time was serving 7,500 special diets a month. The importance of the therapeutic dietitian in other Army hospitals continued to increase.

The teaching dietitian had an important function in the teaching of patients and student nurses, as well as student dietitians. The training school for hospital dietitians at Walter Reed General Hospital brought the medical and surgical departments into closer contact with the dietary department as the officers instructing the group became familiar

34

with the fact that the dietitians were scientifically trained and well able to aid them in their nutritional problems with patients. As these close relationships were continued in other Army hospitals, the dietetic treatment of the patient was improved throughout the Army.

By 1933, the dietitian had become such an important member of the medical team that Maj. Gen. Robert U. Patterson, The Surgeon General, expressed grave concern over the discharge of dietitians because of economy legislation. He stated in a letter to Dr. Malcolm T. MacEachern, Director, American College of Surgeons, that dietitians had come to be considered essential to the proper functioning of Army hospitals. He explained that as many as possible were being retained contingent upon the availability of funds.

Since World War I, there had been no regulations published to standardize and clarify the work of dietitians in the Army. In January 1931, Miss Hunter, chief dietitian at Walter Reed General Hospital, in a letter to The Surgeon General, stated that "The status of the Hospital Dietitian employed by the Army is not generally understood, nor is there a wide appreciation of the difficulties under which she labors." She mentioned that in the more than 12 years during which dietitians were employed by the Army, there had been no material change in their status and no regulations had been published outlining their duties. No action was taken on this letter.

Throughout the thirties, hospital commanders, medical officers, directors of dietetic departments, and the chief dietitian at Walter Reed General Hospital persisted in trying to establish a definite status for Army dietitians. It was still evident that some regulations would have to be published. In 1936, Miss Burns recommended that the circular letter which had defined the status and duties in 191918 be revised to standardize the duties of dietitians in Army hospitals and clarify the problems that dietitians were still facing. Miss Burns stated that "consideration of the duties and status of dietitians in a number of military hospitals indicates the necessity for a general statement defining the dietitians` place and duties."

Brig. Gen. Wallace C. DeWitt, Commanding General, Army Medical Center, Washington, D.C., incorporated Miss Burns` suggestions in a report to The Surgeon General. Information from stations where graduates of the Walter Reed School of Hospital Dietitians were assigned indicated that their services were not always utilized in a manner for which their education and training had adequately prepared them. General DeWitt cited one case in which a dietitian was required to relieve the cook every afternoon. There were even instances where the dietitian occupied a position subordinate to that of the mess sergeant.

Even though a revision to this circular was never published, the fact that all the dietitians received training at Walter Reed General Hospital tended to give uniformity and a high standard of food service in Army hospitals that otherwise could not have been maintained.

18See footnote 9, p. 20.

35

35

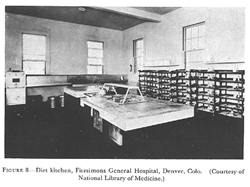

FIGURE 8. Diet kitchen, Fitzsimons General Hospital, Denver, Colo. (Courtesy of National Library of Medicine.)

In July 1937, Maj. Carl R. Mitchell, MC, Director of Dietetics, Walter Reed General Hospital, pointed out that dietitians, as far as their professional work was concerned, should be responsible to the commanding officer. Considering that the dietitians were well educated and thoroughly trained, Major Mitchell thought they should be permitted to exercise the same authority over mess personnel that the head nurse on a ward exercised over ward personnel. Under the mess officer, the dietitian was to be responsible for the entire food service to patients. Her duties were to plan menus for all diets, keep the food cost within the allowance, supervise the preparation and service of all meals to cafeteria (ambulatory) patients, keep a close inspection of waste, direct employees, assist in the ordering of food supplies and the procurement of kitchen equipment, instruct and demonstrate preparation of special diets to patients, and make ward rounds to contact patients, doctors, and nurses.

The conditions under which dietitians worked varied in different installations. The local food products at some hospitals were excellent and the value of the ration entirely adequate because of the economical food supply. In hospitals located on isolated Army posts, it was more difficult to provide a variety of food and to remain within the ration because this allowance did not always advance with the seasonal price of local foods. The general hospitals were allowed the monetary value of

36

36

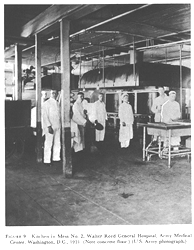

FIGURE 9. Kitchen in Mess No. 2, Walter Reed General Hospital, Army Medical Center, Washington, D.C., 1921. (Note concrete floor.) (U.S. Army photograph.)

the garrison ration plus 50 percent. However, small station hospitals did not receive the extra rations that were allowed the general hospitals, even though they had patients who were on a general hospital status and required special diets. It was necessary for these smaller hospitals to practice the strictest economy, thus making it difficult to maintain high food standards.

The Quartermaster Corps provided food for the hospitals. However, it was sometimes necessary to supplement these supplies by the purchase

37

of fresh fruits and vegetables from local markets. Meats and dairy products at all stations were Government inspected.

In 1925, the value of the ration varied from $0.27 to $0.31, and it was necessary for dietitians to take advantage of low-priced foods such as fish and poultry when in ample supply in the local market. In 1932, the ration was as low as $0.22. On 3 January 1933, the meat component of the garrison or troop ration was amended to include fresh chicken and fresh pork, in addition to the former bacon and fresh beef allowance, and fresh eggs.19 Fresh milk was added for the first time, along with certain fruits and vegetables. Since all Army hospitals were then allowed the garrison ration plus 50 percent, this provided sufficient funds for food for special diets and nourishment.

The ration allowance was adequate during the remainder of the peacetime period. The food served in Army hospitals was of excellent quality. The ration was sufficiently liberal to take care of the patients` needs, and authority to make outside purchases of food and patient welfare items was continued during this period. Selective menus for officers` wards, women`s wards, and officers` messhalls were inaugurated at Walter Reed General Hospital in 1930 and at Fort Sam Houston Station Hospital, Tex., in 1936.

Many hospitals employed civilians for kitchen-police duty and in some instances civilian cooks were employed. In 1941, a training course for enlisted hospital diet cooks was established at Walter Reed General Hospital to train cooks in the preparation and service of diets for patients in small hospitals where no dietitian was assigned.

During the twenties, many improvements were made in mess equipment. These included the installation of labor- and material-saving devices, new ranges, electric mixers, electric meat grinders, electric food choppers, and replacement of the Diller and Dear food carts and containers by the Drinkwater type. Water coolers with ice compartments were placed in many of the mess halls. Ward diet kitchens were equipped with steam tables, electric ranges, electric hot plates, dishwaters, and white top sani-onyx tables (fig. 8). Modern dishwashing rooms were built in general hospital mess halls for the first time. Although some Army hospitals had tile floors, in 1928, The Surgeon General approved the installation of tile floors in mess halls and kitchens in many more Army hospitals, replacing the unsightly concrete floors that were exceedingly difficult to keep clean (fig. 9). Separate cafeteria lines for ambulatory patients as well as enlisted duty personnel were in vogue in most of the general hospital messes at this time. Ambulatory patients on diets were even served in the cafeteria lines. Several electric food carts were used at Walter Reed General Hospital in 1929. Meat-slicing and bread-slicing machines were also in use in many hospitals in 1929. This modern equipment did much to improve the quality of food service in Army hospitals, and it was purchased through the hospital fund in some instances.

19Army Regulations No. 30-2210. Changes No. 1, 3 Jan. 1933.

38

38

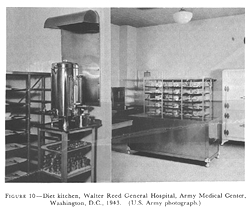

FIGURE 10. Diet kitchen, Walter Reed General Hospital, Army Medical Center, Washington, D.C., 1943. (U.S. Army photograph.)

By 1932, gas-burning broilers and bake ovens, meat, fish, and bone cutters, rotating gas-burning toasters, stainless steel tabletops, stainless steel sinks, electric refrigerators, electric dough dividers, and bread wrapping and sealing machines were in use in at least two Army hospitals. In the mid-thirties, walk-in refrigerators with compartments for different types of food were being installed. Cereal cookers, electric mixers, automatic water heaters, and quick freeze rooms were also being installed. During the late thirties, automatic waffle irons, electric ranges and ovens, electric grills, and steak cubing machines were more widely used. Coffee urns were installed in individual ward kitchens about this time. By 1940, the equipment in the mess departments of the permanent Army hospitals was modern and adequate (fig. 10). Even the smaller station hospitals had replaced much of their old equipment.

By the time World War II was imminent, the ration allowance was sufficient to provide well-balanced and appetizing meals for patients in Army hospitals, and under the supervision of trained dietitians, high standards of food production were being maintained. Adequate equipment and well-trained personnel contributed to the maintenance of these standards during the peacetime years.

Throughout the peacetime period, the champions who had so faith-

39

fully persisted in trying to establish definite duties and status for dietitians in the Medical Department recognized that many of their problems could be solved by military status.

Miss Cooper, Supervising Dietitian in the Surgeon General`s Office at the close of World War I, continued her interest in the status of dietitians in Army hospitals. In reply to a letter written by her to The Surgeon General in 1930, Brig. Gen. Henry C. Fisher, Acting Surgeon General, stated: "At present dietitians on duty in Army general hospitals are in the status of civilian employees and function under the direction of the commanding officer. This is proving a satisfactory arrangement for peacetime. Regarding future emergencies, when the services of large numbers of dietitians might be required as in the World War, * * * a new law must be enacted to give military status to these individuals."

At the end of World War I, Miss Cooper had officially started the fight for legislation which continued for the next 13 years. During this time, many people worked for the establishment of military status for dietitians, among them, Miss Hunter and Miss Burns, chief dietitians at Walter Reed General Hospital; Major Parsons, Director of Dietetics at Walter Reed General Hospital; Col. (later Brig. Gen.) Roger Brooke, MC, Commanding Officer, Fort Sam Houston Station Hospital; and General DeWitt.

Throughout the peacetime years dietitians desired to become a permanent part of the Medical Department. It was the everlasting goal toward which all Army dietitians strived. The education and experience requirements for candidates to be eligible for service as dietitians in the Army were so high and the services that they rendered so important, it was thought that it could only be a matter of time before legislation was enacted making them a permanent group in the Medical Department.

![]()