AMEDD Corps History > Medical Specialist > Publication

CHAPTER III

Physical Therapists Before World War II (1917-40)1

Colonel Emma E. Vogel, USA (Ret.)

Section I. Physical Therapists (1917-19)

THE PHYSICAL RECONSTRUCTION PROGRAM IN THE MEDICAL DEPARTMENT

Physical therapy as a recognized profession in the Medical Department had its beginning in World War I as an important phase of the physical reconstruction program. The experience of European countries already at war had clearly demonstrated the effectiveness of programs to conserve manpower. These programs were directed toward the restoration of the wounded soldier to military duty as soon as possible, or if that was not feasible, to return him to civilian life in a physical condition which would enable him to function in the highest degree possible consistent with his injury.

Since the United States had no experience in such programs early in 1917, Maj. Gen. William Crawford Gorgas, The Surgeon General, designated a committee of Army medical officers to study and report on the program conducted in British Army hospitals. These officers reported most enthusiastically on the program, and, as a result, on 22 August 1917, the Division of Special Hospitals and Physical Reconstruction was established in the Surgeon General`s Office. Physical reconstruction was defined as maximum mental and physical restoration of the individual achieved by the use of medicine and surgery, supplemented by physical therapy, occupational therapy or curative workshop activities, education, recreation, and vocational training. Physical therapy was described as consisting of hydrotherapy, electrotherapy, and mechanotherapy, active exercise, indoor and outdoor games, and massage.

Early in 1918, Dr. Frank B. Granger of Boston, Mass., was appointed a captain in the Medical Reserve Corps and assigned as Chief, Physical Therapy Section, Division of Physical Reconstruction, Surgeon General`s Office. Nationally known as a pioneer in this field, he was well

1(1) Physical therapy was first known as physiotherapy. In World War I, physical therapists were first known as reconstruction aides, and later referred to as physiotherapy aides. However, for the purpose of this history, the terms "physical therapy" and "physical therapists" will be used. (2) The primary source of information for the World War I portion of this chapter is: The Medical Department of the United States Army in the World War. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1927, vol. XIII.

42

42

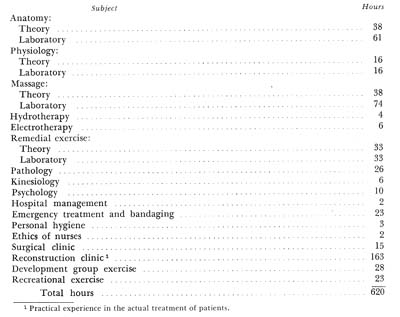

FIGURE 11. Group exercise, 1918. Group of patients administering self-massage and resistive exercise for foot disorders under the direction of Miss Mary McMillan (right).

qualified to introduce this new form of treatment to the Army. Under Captain (later Lt. Col.) Granger`s administrative and professional genius careful selection of personnel was made, standardization of apparatus was initiated, informal instruction of medical officers was initiated, and physical therapy clinics were gradually established on a large scale. In developing this program, Captain Granger was confronted with many obstacles. Many medical officers were skeptical of the values claimed for physical therapy, but reconciled themselves to what they termed an intruder in the medical profession, feeling that it was a passing fad. Some medical officers were so incredulous that the only patients they would entrust to physical therapists were those whose condition could not possibly be impaired by the application of the new therapeutic measures.

The first Supervisor of Reconstruction Aides in the Surgeon General`s Office was Miss Marguerite Sanderson, formerly President, Boston School of Physical Education, who reported for duty in January 1918.2 After several months devoted to organizational and administrative prob-

2The records contain very little information relative to Miss Sanderson`s previous experience in physical therapy other than the mention made of her work with Joel E. Goldthwait, M.D., Boston, Mass., from 1913 to 1915.

43

lems, she was transferred to Walter Reed General Hospital, Washington, D.C., to organize units for oversea hospitals. The first of these units sailed in June 1918. Miss Sanderson went to France in September 1918 where she was assigned as supervisor of reconstruction aides in physical and occupational therapy with the American Expeditionary Forces and later with the army of occupation.

The first physical therapist with the Army, Miss Mary McMillan, reported to Walter Reed General Hospital in February 1918.3 Since she was afforded no clinic space, she administered treatments to patients on the hospital wards and utilized porch space for group exercise (fig. 11). By April, the first hospital physical therapy clinic in the United States opened at Walter Reed General Hospital.4 It was a large U-shaped building5 which consisted of a gymnasium, a large treatment room equipped with plinths and many types of electrical and heating devices, a hydrotherapy section, several small treatment rooms, and administrative offices. Physical therapists assigned to some Army hospitals, however, often found no space nor equipment, and many members of the hospital staff totally unfamiliar with this new specialty. If clinic space was available, it was often in a basement or some other area of the hospital not desired by any other service.

From the very beginning, the physical therapy programs lacked coordination. They were usually conducted in three different areas, that is, treatment in the clinic, in the gymnasium, and on the hospital wards. It sometimes happened that the treatment administered in one section was not known to physical therapists in the other sections, a situation not conducive to optimum therapeutic results. Neither was this treatment known to other members of the hospital staff. Gradually, a system of records was evolved to incorporate all of the patient`s treatment on one card which was then available to all interested personnel.

With the return of a large number of disabled men in the months following the armistice, it became necessary to expand the physical therapy program. The number of physical therapists employed increased commensurately with the increase in the number of hospitals equipped with physical therapy facilities (table 1).

The contributions made by physical therapists are well summarized in the following statement made by a medical officer who served in physical therapy clinics of three different hospitals during the war:6

I have never known of anything approaching the devotion of these girls to their work. They worked hard all day, attended lectures on technic after hours, held quizzes during the noon hour and in the evenings and could be found in the clinic until late hours trying out technics one upon the other * * *. No corps ever displayed greater loyalty, more unselfishness, greater devotion to

3Miss McMillan had had extensive training and experience in physical therapy in British hospitals before coming to the United States in 1915.

4Kovács, Richard: Electrotherapy and Light Therapy With the Essentials of Hydrotherapy and Mechanotherapy. 4th edition. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1942, pp. 23, 686.

5Since April 1918, the building has been renovated many times and now houses the Officers` Open Mess at Walter Reed Army Medical Center.

6Sampson, C. M.: Physiotherapy Technic. St. Louis: C. V. Mosby Co., 1923, pp. 9, 412-413.

44

duty or a better general high average of efficiency, from the chief aide to the humblest assistant aide, than did the reconstruction aide body during the heaviest work of the reconstruction period. Their esprit de corps became a thing remarked upon by all who observed their work.

Investigation showed that there were very few people in the United States who had had any education or experience in the field of physical therapy. The procedures were too technical to be administered by untrained personnel. Accordingly, it was proposed in September 1917 that the Army establish a physical therapy training course at the Soldiers` Home, Washington, D.C., for both physical therapists and enlisted men. For reasons not recorded, however, the plan did not materialize.7

Since the training of physical therapists had never before been attempted in this country, The Surgeon General invited several prominent educators to a conference in his office to discuss the problem which confronted him. As a result of this conference, an appeal was made to physical education schools to cooperate in establishing short intensive emergency physical therapy training programs. Early in 1918, The Surgeon General approved the outlines and plans submitted by the schools which were willing to undertake this training. In April, emergency physical therapy courses were initiated at the following institutions: American School of Physical Education, Boston, Mass.; Boston School of Physical Education, Boston, Mass.; Prose Normal School of Gymnastics, Boston, Mass.; New Haven Normal School of Gymnastics, New Haven, Conn.; Normal School of Physical Education, Battle Creek, Mich.; and Reed College, Portland, Oreg.

The largest enrollment was at Reed College where 200 students representing 72 universities or colleges and 31 states attended the second course.8 In June 1918, at the urgent request of the president of Reed College, The Surgeon General granted Miss McMillan leave of absence from Walter Reed General Hospital to accept the position of director

7See footnote 1 (2), p. 41.

8(1) War Work For Women. Reed College Record, Portland, Oreg., No. 29, May 1918, and November 1918. (2) One of the students who graduated from Reed College was Miss (later Col.) Emma E. Vogel.

45

of the reconstruction clinic and instructor in massage for the emergency course at Reed College.9

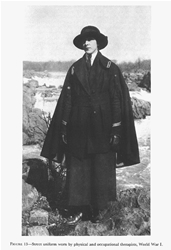

It is believed that the curriculum offered at Reed College in 1918 was typical of the other emergency physical therapy training courses:

Its shortcomings were obvious before the first course was completed and it was planned that if necessary to continue the program, later courses would be more comprehensive. After the signing of the armistice, the emergency courses were terminated upon the completion of the courses then in progress.

Since exercise was to play a major role in the rehabilitation process, preference in the selection of students to attend these courses was given to those with high scholastic standing in the fundamentals of physical education. It is interesting to note that in evaluating the physical therapy program during World War I, Major Granger stated that in his opinion the best physical therapists were those who, prior to taking their physical therapy training,10 had been graduated with a major in physical education.

9When this training program was terminated after the signing of the armistice, Miss McMillan returned to Walter Reed General Hospital. After being promoted to the grade of supervisor in October 1919, she served in an advisory capacity to The Surgeon General until 1920 on matters pertaining to the inactivation of physical therapy clinics and the discharge of physical therapists. Shortly after Miss McMillan`s departure, in 1920, Miss Emma E. Vogel was appointed to the position of supervisor of physical therapists at Walter Reed General Hospital.

10Granger, Frank Butler: Physical Therapeutic Technic. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders & Co., 1929, p. 164.

46

46

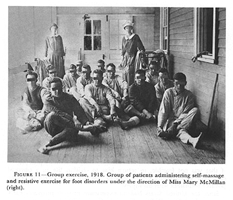

FIGURE 12. Uniform worn by physical therapists in some Army hospitals, 1920. Physical therapist is giving peripheral stimulation by means of a high frequency vacuum tube.

In July 1918, the medical director of physical therapy at Walter Reed General Hospital recommended to The Surgeon General that a course of training be immediately established at that hospital. The recommendation was based on the shortage of women adequately trained for military physical therapy. Such a program, however, was not implemented until 1922.

The exact number of physical therapists who served with the Medical Department during World War I is not known. From the available records, it appears that approximately 800 physical therapists were so appointed, most of whom were graduates of the emergency training courses.

The physical therapists` hospital uniform was a blue one-piece garment with a belt of the same material and detachable white collars and

47

cuffs. In some hospitals, they chose to wear a uniform and white apron similar to that worn by occupational therapists (fig. 12). The cap worn by the staff physical therapists had a crown of blue organdy with a white band. The head physical therapist`s cap was entirely white.

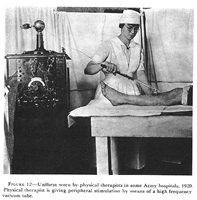

The street uniform worn by physical and occupational therapists during World War I was a two-piece dark gray suit, with a band of maroon and white braid on the sleeves. Worn with this was a partially belted cape of the same material, a black velour sailor-type hat (black straw for summer) trimmed with a maroon cockade and white braid, black hose, and high black shoes (fig. 13). Physical therapists going overseas were required to purchase and wear the prescribed street uniform, but its purchase and use in this country were optional. The insignia consisted of the bronze letters "R.A." (Reconstruction Aide) It was worn at the collar opening of the hospital uniform and on the lapels of the jacket and cape. Bronze caducei were worn on the lapels of the hospital uniform.

Army Hospitals in the United States

Since physical therapy was a newcomer in the medical world, many ward surgeons preferred to prescribe the treatment to be given to their patients. In most instances, the medical director of physical therapy was not authorized to prescribe the modality to be employed, or to make changes in the progression from passive to active exercise, for example, without consulting the ward surgeon concerned with the case. This system had one advantage in that the ward surgeons often came to the clinic to observe their patients, and with each visit they became more interested in physical therapy. It had the disadvantage of preventing the director of physical therapy from exercising his initiative and medical judgment.

By far the most time-consuming and the most popular form of physical therapy was massage which was prescribed for practically all patients (fig. 14). Unfortunately, its use was abused and often it was prescribed as a placebo. From records available, it appears that massage constituted about 40 percent of the total number of treatments administered while various types of exercise constituted only about 25 percent. Physical therapy measures were effectively used in the treatment of many conditions, but it was in the care of patients with orthopedic conditions and peripheral nerve lesions that it proved to be a most valuable adjunct. Space does not permit a discussion of all the types of patients treated by these procedures, hence only two of the larger groups will be discussed.

Amputations

Of the orthopedic conditions treated, patients with amputations constituted a very large percentage. Most of these patients had had no

48

48

FIGURE 13. Street uniform worn by physical and occupational therapists, World War I.

49

treatment other than initial surgery, usually a guillotine amputation performed in a field hospital. Consequently, these conditions were often complicated with infection, sequestra, contractures, deformities, bone and muscle atrophy, massive scar tissue, and edema. After corrective surgery, the routine physical therapy measures for amputees usually consisted of whirlpool baths or some form of dry heat and massage to mobilize scar tissue and reduce edema and passive exercise to stretch contracted muscles. This was usually followed by pressure exercises to toughen the stump end and the application of an elastic-type pressure bandage to assist soft tissue shrinkage. It was the responsibility of the physical therapist to instruct the amputee in the hygienic care of his stump, and, after the prosthesis was fitted, to instruct him in its use. Balance and walking exercises and games for at least an hour a day were stressed for lower extremity amputees; activities of daily living were emphasized for upper extremity amputees.

Peripheral nerve injuries

The treatment of patients with peripheral nerve lesions was discouraging to both the patient and physical therapist. Because of many months of inactivity, often with inadequate or no splinting, these patients usually demonstrated marked bone and muscle atrophy, extensive scar tissue involving nerves and tendons, and marked contractures and deformities, sometimes further complicated with causalgia, hyperesthesia, and circulatory conditions. After corrective surgery and splinting were accomplished, physical therapy procedures usually consisted of whirlpool baths, massage and stretching of the contracted muscles, re-educational exercises, and electrical stimulation of some type for paralyzed muscles. It is significant to point out here that, perhaps for the first time, galvanic and faradic currents were employed in determining the site and extent of the nerve lesion. Perhaps also for the first time, the physical therapist was called upon to give muscle strength (sometimes called "classification of muscle action") and sensory nerve tests. Copies of these tests were incorporated into the patient`s permanent hospital record. At specialized hospitals where these patients were assigned, unlimited opportunities existed for the physical therapists to gain experience in use of various testing procedures and in evaluation of treatment. For example in one hospital, 1,700 patients with peripheral nerve injuries were hospitalized, over 600 at one time. 11 In many Army hospitals, medical officers on the neurosurgical service conducted special courses for physical therapists, stressing anatomy, muscle and sensory nerve distribution, and simple diagnostic tests for the common nerve injuries.

Army Hospitals With the American Expeditionary Forces

The physical therapy program in hospitals (fig. 15) supporting the

11See footnote 6, p. 43.

50

50

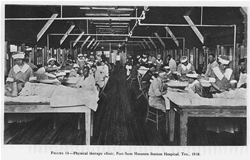

FIGURE 14. Physical therapy clinic, Fort Sam Houston Station Hospital, Tex., 1918.

51

51

FIGURE 15. Physical therapy clinic, U.S. Army Base Hospital, France, 1918. (Courtesy of National Library of Medicine.)

American Expeditionary Forces did not become as highly organized as it was in the Army hospitals in the United States, nor was it planned that it would be. Patients requiring long periods of hospitalization who would receive the most benefit from this type of treatment would be returned to the United States.

Approximately 80 physical therapists were assigned with the American Expeditionary Forces in late 1918.12 By 15 March 1919, this number had been reduced to 71 and by 1 May 1919, that number had been further reduced to 54 assigned in 14 hospitals. 13 The records contain only meager reports of physical therapy activities in hospitals supporting the American Expeditionary Forces, but it is believed that the

12Report of The Surgeon General, U.S. Army. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1919, p. 1178.

13The Medical Department of the United States Army in the World War. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1927, vol. II, p. 129.

52

description of activities extracted from the report of the Savenay Hospital Center, France, is typical.

In October 1918 when four physical therapists arrived at the Savenay Hospital Center, their services were immediately utilized to assist the nurses in the care of a large influx of patients resulting from an influenza epidemic. As soon as this situation subsided, physical therapy was started in a small clinic. In December, a new clinic was opened in a large well-ventilated and well-equipped room and the number of physical therapists was increased to 30. Patients treated included those with gunshot wounds, peripheral nerve injuries, joint injuries, spinal cord and head injuries, amputations, trenchfoot, and many other conditions. When practicable, patients were grouped for curative exercises. These treatments were administered both in the clinic and on the hospital wards. During the winter months, a series of lectures were arranged for the physical therapists, and included such subjects as the pathology of contracture deformity, correction of contracture deformity by surgical and nonsurgical methods, use of splints and casts, mechanical treatment of joint injuries, and other allied subjects. The physical therapy program continued to function to full capacity until the discontinuance of the center.

Army Hospitals With the Army of Occupation

When the Third U.S. Army (army of occupation) established headquarters in Germany in January 1919, the surgical and orthopedic patients were concentrated in 2 evacuation hospitals to which 13 physical therapists were assigned. As the Third U.S. Army was reduced in size after the signing of the final terms of peace on 28 June 1919, the supporting hospitals were closed, and the physical therapists returned to the United States soon afterward.

Section II. Physical Therapists (1919-40)14

Before World War I, there were very few physicians actively practicing physical therapy in the United States and these were often looked upon by the majority of their colleagues with suspicion.15 Scattered groups of enthusiasts practiced electrotherapy in one area, hydrotherapy in another, and massage and manipulation in another. There were no physical therapy clinics in civilian hospitals where procedures could be evaluated or where research could be done. After the war, there became available several hundred physical therapists and an increasing number of physicians who had their first indoctrination in

14Information for the 1919-40 portion of this chapter is contained in the annual hospital reports submitted to The Surgeon General and the annual reports of The Surgeon General submitted to the Secretary of War during this period, supplemented by the author`s personal files and knowledge.

15See footnote 4, p. 43.

53

physical therapy while serving in the Army. As a result, civilian practice in this field was given a tremendous impetus.

The organization which is known today as the American Physical Therapy Association was founded in 1921 by a nucleus of physical therapists who were or who had been in the service. Two objectives of this organization were "* * * to establish and maintain a professional and scientific standard for those engaged in the profession of physical therapeutics; [and] to increase efficiency among its members by encouraging them in advanced study."16 Doctor Granger who assisted in the formation of the organization emphasized: "It is now necessary for you to maintain inviolate the high standard which you have initiated, but also by your influence and example to advance it to a still higher plane of usefulness and exactness." Miss McMillan was elected the first president of the organization and served until 1923.

During the twenties, the practice of physical therapy in the United States exceeded all expectations. The profession was sometimes widely exploited by cultists, and for a time, it seemed that overenthusiasm based on limited knowledge and experience threatened the future of this specialty. With a view toward placing the profession on a scientific basis, the American Academy of Physiotherapy was organized with Doctor Granger as its president. At the first meeting in Atlantic City, N.J., on 17 September 1923, Doctor Granger stated, "The World War resulted in the real birth of physiotherapy, and as a result it has begun to assume its rightful place in the medical world."17 He pointed out the great need for standardization and recommended the establishment of a committee composed of physicians, electrical engineers, manufacturers, and representatives of the National Bureau of Standards to evaluate and standardize all electrical equipment.

During the rapid expansion of the profession, little attention was given to professional standards, ethics, or training and some commercial establishments even offered physical therapy training through correspondence courses. Because of this, in 1934, the House of Delegates of the American Medical Association passed a resolution stressing the need for control of the profession. As a result, in 1936, the Council on Physical Therapy (established in 1925) cooperated with the Council on Medical Education in making a survey of treatment practices and training courses.18 After inspection by the latter council, a list of approved schools was published.

As the World War I patients were discharged to return to civilian

16Hazenhyer, I. M.: A History of the American Physiotherapy Association. Phys. Therapy Rev. 26: 3-14, January-February 1946.

17Presidential Address, Frank B. Granger, M.D., before the first convention of the American Academy of Physiotherapy, Atlantic City, N.J., 17 Sept. 1923.

18See footnote 4, p. 43. Dr. Kovács states (p. 24) that the Council on Physical Therapy was formed in 1927. However, "The Board of Trustees reported the establishment of a Council on Physical Therapy in May 1925." From A.M.A. Digest of Actions of Board of Trustees, 1846-1958.

54

life or were transferred to other hospitals, there was a general cutback in the physical therapy program in Army hospitals (table 2).

By 30 June 1921, the number of hospitals supporting this program had been reduced to six, namely:

Army and Navy General Hospital, Hot Springs, Ark.

Fitzsimons General Hospital, Denver, Colo.

Letterman General Hospital, San Francisco, Calif.

Fort Sam Houston Station Hospital, Tex.

Walter Reed General Hospital, Washington, D.C.

William Beaumont General Hospital, El Paso, Tex.

In the years following World War I, the Army focused its attention on stabilizing and standardizing physical therapy procedures. The gradual cutback in the number of physical therapists resulted in a careful screening of patients to exclude those for whom this treatment had been prescribed merely as a placebo.

During World War I, there were no medical officers assigned at the hospital level with any formal physical therapy training, because such training was not available in this country. The Army recognized this need, and in 1922, Maj. James B. Montgomery, MC, was directed to take instruction with Doctor Granger, who by that time had returned to Boston. Upon completion of this training, Major Montgomery was assigned to Walter Reed General Hospital to reorganize the physical therapy service and to act as an adviser to The Surgeon General on matters pertaining to this specialty. Maj. (later Brig. Gen.) Harry D. Offutt, MC, who succeeded him, also had physical therapy training. So far as is known, these are the only Army medical officers so trained during the early post-World War I years.19

In contrast to some of the hyper enthusiasts who preceded him, Major Montgomery was ultraconservative. Through his efforts close cooperation and liaison with the other hospital services were soon established. Ward surgeons no longer prescribed physical therapy procedures, instead they stated the desired objectives and relied on Major Montgomery`s judgment to accomplish treatment. In other Army general hospitals, physical therapy activities were nominally under the direction of the chief of the medical, surgical, or X-ray service.

19During World War II, Col. Harry D. Offutt, MC, was assigned to the Surgeon General`s Office as Chief, Hospitalization Division, where he was extremely helpful in advising on the many administrative problems concerned with the expansion of the physical therapy program and in promoting military status for physical therapists and dietitians.

55

In order to effect coordinated patient care, Major Montgomery recommended that physical therapy and occupational therapy be under the same medical direction and that the basic medical education of these women be the same. As a result, the liaison between these two groups was improved. Subsequently, a coordinated treatment program was developed which in turn resulted in improved patient care.

In general, the status of physical therapy in Army hospitals was in direct proportion not only to the interest and ability of the medical officer in charge, but also to the professional and administrative abilities of the chief physical therapist. With frequent changes in medical supervision, the continuity of the program came to be more and more the responsibility of the chief physical therapist. While there were no directives delineating her duties, it came to be understood that she was responsible for the supervision of patient physical therapy care, training of her staff, and liaison with other hospital services.

All vacancies in the position of physical therapist in Army hospitals were filled by graduates of the training course at Walter Reed General Hospital from 1922 until 1938. This was a great advantage. Familiarization with standardized techniques and Army procedures greatly facilitated their adjustment in new assignments and afforded continuity to all the physical therapy programs.

The permanent inclusion of physical therapy in the Medical Department hospitalization program was assured when physical therapy clinics were incorporated in all of the Army hospitals constructed during the twenties and thirties. On 1 July 1921, William Beaumont General Hospital received its first patients in a permanent two-story building replacing the temporary cantonment-type structure built during World War I. The new physical therapy clinic was well equipped with the most modern apparatus available at that time. In July 1930, the physical therapy clinic at Walter Reed General Hospital was moved from a temporary type of building to the ground floor of the so-called clinic building. The new physical therapy clinic, equipped with all the latest types of apparatus and regarded as a model department, was visited by many Army medical officers and civilian physicians as well as medical students in the Metropolitan Washington area. It also contained a large lecture and laboratory room for instructional purposes.

The Army and Navy General Hospital, established in 1886, was replaced in 1933 by a permanent-type structure. As did the old hospital before it, the new hospital utilized the therapeutic properties of the mineral hot springs in that area. The hydrotherapy section included the first therapeutic pool in the Army. It was patterned after the one at Warm Springs, Ga., and was equipped with weighted tables and chairs and an overhead carriage for conveying a chair or litter into the pool. Physical therapists used the pool to great advantage in giving underwater exercise to patients with arthritis.

The Fort Sam Houston Station Hospital was replaced by a modern permanent building in 1938 and was redesignated Brooke General Hos-

56

pital in 1942. This new building included a large physical therapy clinic, well equipped with all the latest types of electrical and manual exercise apparatus and a modern hydrotherapy section.

From 1 July 1919 to 1 July 1920, inclusive, the number of physical therapists serving with the Medical Department decreased from 558 to 175. At Walter Reed General Hospital, the number of physical therapists decreased from 62 on 1 October 1919 to 24 on 1 June 1920. This was typical of the rate of demobilization of physical therapists throughout the Army.

Upon discharge from the Army, many physical therapists were employed by the U.S. Public Health Service, and after 1921 by the Veterans` Bureau (now Veterans` Administration). Others were employed in industrial accident clinics or in schools for crippled children, both new ventures for physical therapists in the United States. Some were employed by orthopedic surgeons who had come to realize the value of physical therapy during their wartime experience.

For several years, physical therapists were assigned only in general hospitals, and then in limited numbers except at Walter Reed General Hospital where the physical therapy training course was conducted. It was not until the mid-thirties that commanding officers in a few station hospitals in the United States requested the assignment of a physical therapist. In the absence of directives, each department functioned in accordance with local hospital regulations. From 1920 to the late thirties, there was a constant turnover of physical therapists in Army hospitals. The rapid expansion of physical therapy in civilian and other federal hospitals frequently lured experienced and well-trained Army physical therapists to more remunerative positions.

In 1926, a survey made by Miss Emma E. Vogel, Supervisor, Physical Therapists, Walter Reed General Hospital, revealed that the salaries of Army physical therapists were not consistent with current standards. As a result of this study, The Surgeon General recommended that an improved salary scale be established.20 Because of lack of funds it was never implemented. At this time, The Surgeon General directed that the use of the term "reconstruction aide" be discontinued in favor of the term "physiotherapy aide."

In 1931, Miss Vogel conducted another survey which revealed that there had been no material improvement in the salary or status of physical therapists since World War I.21 Since it had been demonstrated that physical therapy was essential to the Army, it was Miss Vogel`s contention that salaries should be sufficient to warrant the re-

20Vogel, Emma E.: Physical Therapists of the Medical Department, United States Army, pp. 15-16.

21Letter, Emma E. Vogel, Supervisor, Physiotherapy Aides, Walter Reed General Hospital, to The Surgeon General, through channels, 9 Feb. 1931, subject: Request for Increased Salary and Recognition for Physiotherapy Aides.

57

tention of experienced personnel to carry on this program. Her report to The Surgeon General contained the following recommendations:

1. Establishment of an improved salary scale commensurate with years of service and responsibilities.

2. Authorization of advanced study on a detached service basis, the same as enjoyed by members of the Army Nurse Corps.

3. Establishment of a Medical Auxiliary Corps to consist of dietitians, physical therapists, and occupational therapists with the same salary, rights, and privileges as the Army Nurse Corps.

4. Establishment of a Reserve Corps to consist of graduates of the training courses in these three specialties at Walter Reed General Hospital and former employees of the Medical Department in these categories. However, again because of the lack of funds, no action was taken.

From 1919 to 1939, physical therapists and other civilian employees experienced considerable uncertainty as to the security of their positions, because there was no regular appropriation of funds for their salaries. From 1919 to 1924, these salaries were paid from Medical and Hospital Department (Army) funds. Beginning in 1924, many salaries were paid from funds which were received by the Army for the hospitalization of patients by the Veterans` Administration. The salaries of physical therapists were the same as those of the dietitians. (See Appendix B, p. 595.)

In 1933, the provisions of the National Economy Act resulted in a reduction of funds due to the cutback in the number of veterans being hospitalized in Army hospitals for non-service-connected disabilities. Consequently, the physical therapy program was drastically curtailed in some hospitals and discontinued altogether in others. The sudden reduction from 15 to 3 physical therapists at Walter Reed General Hospital was typical of changes which occurred in other Army general hospitals. The physical therapy clinic at Walter Reed General Hospital would have closed its doors had it not been that the three remaining physical therapists were willing to serve at reduced salaries and that students graduating from the training course that year volunteered to remain on duty with no compensation other than quarters and subsistence. In the 1933 annual report of Letterman General Hospital, the physical therapists were commended for their high morale and cooperation during this critical period when they worked far beyond their normal capacity. In 1933, local hospital funds were again augmented when members of the Civilian Conservation Corps were admitted to Army hospitals. Physical therapists were re-employed at reduced salaries. This situation continued until February 1939 when physical therapists were placed under the competitive classified system of the Civil Service Commission.22 This status assured salaries paid from appropriated funds but contributed little to relieve feelings of

22Executive Order No. 7916, 24 June 1938, subject: Extending the Competitive Classified Civil Service.

58

insecurity. These events, however, dramatically demonstrated the need for a permanent military status.

In August 1938, in addition to the 10 physical therapists assigned to Walter Reed General Hospital, there were 27 assigned in 15 Army hospitals outside the District of Columbia, as follows:23

|

Army and Navy General Hospital, Hot Springs, Ark. |

4 |

|

Fitzsimons General Hospital, Denver, Colo. |

6 |

|

Letterman General Hospital, San Francisco, Calif. |

3 |

|

Fort Bragg Station Hospital, N.C. |

1 |

|

Fort Jay Station Hospital, Governors Island, N.Y. |

1 |

|

Fort Leavenworth Station Hospital, Kans. |

1 |

|

Fort Riley Station Hospital, Kans. |

1 |

|

Fort Sam Houston Station Hospital, Tex. |

3 |

|

Fort Sill Station Hospital, Okla. |

1 |

|

Fort Francis E. Warren Station Hospital, Wyo. |

1 |

|

Schofield Barracks Station Hospital, T.H. |

1 |

|

U.S. Military Academy Station Hospital, West Point, N.Y. |

1 |

|

Sternberg General Hospital, Manila, Philippine Islands |

1 |

|

Tripler General Hospital, T.H. |

1 |

|

William Beaumont General Hospital, El Paso, Tex. |

1 |

|

Total |

27 |

This small group of physical therapists constituted the nucleus around which the World War II expansion program was developed. Those with administrative and teaching experience later became the directors of the World War II emergency physical therapy training courses.

The annual report of The Surgeon General to the Secretary of War in 1919 stated that in May of that year the total number of physical therapists on duty was 700. Economic pressures imposed with the termination of hostilities and the gradual reduction in the number of hospital patients resulted in a rapid decrease in the number of physical therapists employed.

By late 1921, the separation of physical therapists had been accelerated to such an extent that the Medical Department was faced with an acute shortage of this personnel. By this time, those who had served in the Medical Department during the war had become established in more remunerative positions and were not interested in returning to the Army. Since there were no basic physical therapy training courses in the United States at that time, Major Montgomery recommended that the Medical Department initiate its own training program. The plan was concurred in and the first postwar basic physical therapy training program was established at Walter Reed General Hospital in the fall of 1922.24 This course was organized as a part

23Physiotherapy Aides on Duty at Army Hospitals, Outside the District of Columbia, 19 Aug. 1938.

24Letter, The Surgeon General to Commanding Officer, Walter Reed General Hospital, 16 Aug. 1922, subject: Establishment of a Course of Training for Physiotherapy Aides at Walter Reed General Hospital, with 5 indorsements thereto.

59

59

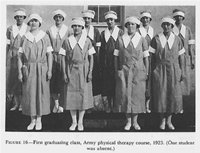

FIGURE 16. First graduating class, Army physical therapy course, 1923. (One student was absent.)

of the Medical Department Professional Services Schools at the Army Medical Center under the command of Brig. Gen. James D. Glennan. The course was directed by Major Montgomery who was assisted by Miss Vogel. Eleven students completed this course in February 1923 (fig. 16).

The first course of 4 months` duration was available to qualified applicants who had satisfactorily completed not less than 2 years in an accredited school of physical education.25 At that time there were a few 2-year physical education courses although the majority were 3-and 4-year courses. Prior to acceptance of her appointment, each student agreed that if she were later appointed as an Army physical therapist she would serve for at least 1 year.

The curriculum included subjects which were taken at the Army School of Nursing also conducted at the Army Medical Center (table 3). Courses pertaining to physical therapy techniques were taught by physical therapists. It was first thought that courses in anatomy, physiology, and bandaging could be taken with student nurses, but after a trial, it was decided that these subjects were more valuable to the student if the subjects were presented from the physical therapy viewpoint. Generally speaking, the course consisted of theoretical and practical instruction, demonstrations, and supervised practical application of techniques in the treatment of patients.

25Prospectus of the Hospital Training Course in Physiotherapy for Aides, Army Medical Center, Walter Reed General Hospital, 1925.

60

The graduation address for the first course was given by Colonel Granger.26 In this talk, he paid high tribute to the World War I physical therapists:

Their loyalty, their enthusiasm, their painstaking care, their professional ability, and their personality, not only were mighty factors in raising the morale and hastening the cure of the wounded in the hospitals, but also in providing to the too often skeptical medical officer the value of scientifically applied physical

26Graduation Address, Physical Therapy Course, Walter Reed General Hospital, by Lt. Col. Frank B. Granger, MC, 7 Feb. 1923.

61

measures. All honor to the 815 Reconstruction Aides in physical therapy, picked from among several thousand applicants. * * * 95% of the aides were either graduates of normal schools of physical education or were college graduates who had majored in physical education. These aides all received at least 6 weeks of intensive training in physical therapy before being accepted by the Army * * *. You are heiresses to this high heritage, and I give it to you strictly in charge never to let any act of yours sully it in the slightest degree.

That the training program had impact on the care of patients and on the conduct of the physical therapy department itself is borne out by The Surgeon General`s Annual Report, 1924, which contains the following comments submitted by the Commanding General, Army Medical Center: "The instruction and training of the junior aides under the direction of the Supervisor of Physiotherapy Aides has been well blended into the functioning of this department, and in addition the stimulative effect of this training has been of immense value to the department in maintaining efficient and cooperative work."

The length of the course and the prerequisites for appointment proved inadequate for producing the type of professional women desired by the Army. The course was lengthened to 6 months in 1924, 8 months in 1930, 9 months in 1932, and to 12 months in 1934, and the requisite education was increased from 2 years to completion of 4 years of college, with emphasis in physical education. A comparison of the curriculums of the 4- and 12-month courses is shown in table 3. This course was given annually at Walter Reed General Hospital beginning in 1922, with the exception of the year 1933-34 when this training program and other Army hospital activities were suspended because of provisions of the National Economy Act (chart 1).

The length of the physical therapy course was decreased from 12 months in 1938 to 10 months in 1939 and to 9 months in 1940. These reductions were made possible through the gradual elimination of courses which, while interesting, were nevertheless believed not to be essential to the basic training of physical therapists.

In 1928, when the American Physiotherapy Association assumed the function of a professional accrediting agency, the Army physical therapy training course was among the first to be accredited.27 In 1936, when the Council on Medical Education and Hospitals of the American Medical Association became the official accrediting body for such courses, this course was approved28 and continued to be approved.

In the early thirties, short courses were conducted to orient medical officers and students in the Army School of Nursing to physical therapy.

There was a marked change in the emphasis in Army physical therapy from 1920 to 1940, inclusive. The general trend was away from the "bake and massage" techniques which had been almost

27Approved School for Physical Therapy Technicians. J.A.M.A. 114: 1262-1263, 30 Mar. 1940.

28Survey of Schools for Physical Therapy Technicians. J.A.M.A. 107: 676-679, 29 Aug. 1936.

62

63

routinely included in patient prescriptions during World War I, to a program directed toward the patient`s active participation in his rehabilitation. The emphasis shifted from treatment of an injured extremity to treatment of the patient as a whole. For example, exercise for orthopedic patients was directed not only to the injured extremity but also to the maintenance of good posture and normal muscle tone and range of motion in the uninjured extremities. To some extent, it may be said that this new concept of exercise which began in the twenties was the forerunner of what was to be known as physical reconditioning during World War II. There was also more emphasis on the human relations aspect and the patient-physical therapist relationship in the patient`s recovery. A clean, cheery, well-organized physical therapy clinic staffed by well-groomed and capable physical therapists was found to be a strong morale factor for both patients and personnel.

Space does not permit a discussion of the many changes made between 1920 and 1940; a few, however, will be mentioned.

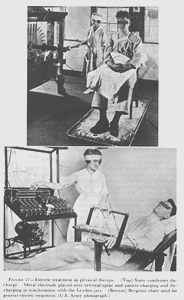

Treatment by use of the static machine and Bergonie chair, which had been administered largely for psychological effect during World War I, was discontinued altogether in the late twenties (fig. 17). During this same period, diathermy was used extensively in many general hospitals in the treatment of patients with pneumonia. It was believed that this treatment produced a stimulating effect on the body`s normal defensive mechanism and gave symptomatic relief. These treatments were normally of 30 minutes` duration, administered every 4 hours until midnight.

During the late thirties, hyperpyrexia (induction of artificial fever by physical measures) in selected cases was initiated. Although the apparatus was not always located in the physical therapy clinic, the responsibility of administering this treatment was usually delegated to the medical director of physical therapy (assisted by specially trained nurses). With the development of the sulfonamide and penicillin compounds, the need for artificial fever decreased. It was still used for some years, however, in treatment of eye conditions.

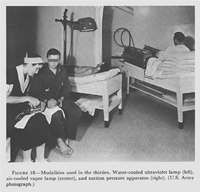

Another innovation during the thirties was the use of the suction pressure apparatus, sometimes called the "Glass Boots." The equipment consisted of two plastic boots attached to a motor-driven apparatus which produced an alternating negative and positive pressure within each boot. This treatment proved beneficial in the treatment of selected patients with peripheral and vascular disturbances (fig. 18).

At Fitzsimons General Hospital, irradiation from alpine and carbon arc lamps was used for the general tonic effect for tuberculous patients not only to supplement heliotherapy on cloudy days, but also to treat those patients who were unable to tolerate heliotherapy exposures for various reasons. Carefully supervised and graduated exercises for tuberculous patients initiated at that hospital in the early twenties were continued throughout the years. In the thirties, ultraviolet ir-

64

64

FIGURE 17. Electric treatment in physical therapy. (Top) Static condenser discharge. Metal electrode placed over cervical spine and patient charging and discharging in synchronism with the Leyden jars. (Bottom) Bergonie chair used for general electric treatment. (U.S. Army photograph.)

65

65

FIGURE 18. Modalities used in the thirties. Water-cooled ultraviolet lamp (left), air-cooled vapor lamp (center), and suction pressure apparatus (right). (U.S. Army photograph.)

radiation of open thoracoplasties was found to be beneficial in the healing process.

At Walter Reed and Letterman General Hospitals, hydrotherapy, systematic setting-up exercises, and progressive Goldthwait exercises sometimes supplemented by dancing and games were introduced in the treatment of neuropsychiatric patients.

In the late thirties, the physical therapy clinics at several general hospitals cooperated with the National Bureau of Standards and the U.S. Army Signal Corps in carrying out a series of tests on the first short-wave apparatus. Patients who volunteered for these tests reported that the heat generated by this apparatus expedited relief from pain and was more soothing than that generated with the conventional diathermy apparatus. Since the current produced by this machine seriously interfered with radio transmission and reception, it was recommended that procurement of this apparatus be delayed until changes in its construction had been accomplished.

66

When the President proclaimed a limited national emergency on 8 September 1939, the Medical Department took stock of its resources and found that physical therapy was faced with three immediate major problems: The procurement of professional personnel, both medical officers and physical therapists; equipment; and floor plans for physical therapy clinics.

Experience during the years clearly demonstrated that the medical director of the physical therapy service should be specially trained in this field. Shortly after the President`s proclamation, plans were formulated in the Surgeon General`s Office providing opportunities for interested medical officers to pursue 3 months of training in this specialty. Other interested officers were given on-the-job training by these specially trained officers. This program continued for several years and eventually the physical therapy clinics in all Army general hospitals in the United States were under the direction of officers who had completed this training.29 However, the number of officers so trained was not sufficient to staff physical therapy clinics in oversea hospitals and in station hospitals in this country.

The procurement of a sufficient number of physical therapists in the event of war presented an even graver problem. In 1940, there were only 15 physical therapy courses approved by the Council on Medical Education and Hospitals of the American Medical Association, including the course conducted at Walter Reed General Hospital. Since the number of physical therapists in the entire country was far short of meeting both civilian and anticipated military needs a markedly accelerated Army physical therapy training program was mandatory (ch. VI, pp. 137-182).

On 6 March 1939, The Surgeon General communicated with the Director of the American National Red Cross, Washington, D.C., outlining Medical Department needs in the event of mobilization. In a series of subsequent conferences,30 it was agreed that the Red Cross would enroll physical therapists who would constitute an immediately available reserve to meet anticipated requirements during the first 4 months following mobilization. This plan was approved, and in early 1940, The Surgeon General requested that the Red Cross initiate this enrollment as soon as practicable. Reporting on the progress of this enrollment, the Red Cross advised on 30 June that 1,200 announcements had been mailed to qualified physical therapists, 62 had completed applications, and 14 had enrolled.31 This program was handicapped because physical therapists were required to take the civil service examination after enrollment with the Red Cross. Since these

29War Department Technical Manual 12-406, 30 Dec. 1943.

30Report of Conference Between Representatives of the American National Red Cross and The Surgeon General of the Army, 10 Apr. 1939.

31Report, American [National] Red Cross, subject: Enrollment of Medical Technologists, 30 June 1940.

67

individuals were enrolling with the Red Cross not to seek permanent employment with the Army, but rather to make themselves available in the event of a national emergency, the Civil Service Commission waived its requirement of certification. Although this program was not effective in procuring physical therapists, it did serve a useful purpose, in that it publicized the acute shortage of this personnel available for military service.

Surveying its stock of equipment, the Medical Department became acutely aware that there was no reserve of physical therapy equipment. Preparation of new equipment lists begun in January 1939 was far from complete.32 The Medical Department Board and the Surgeon General`s Office realized the need to bring the physical therapy equipment list up to date and requested the assistance of Capt. (later Brig. Gen., USAF) Benjamin A. Strickland, Jr., MC, Director of Physical Therapy, Walter Reed General Hospital. The procurement of equipment in an already tightening civilian market presented many problems. A few fly-by-night manufacturing concerns began to produce physical therapy equipment, which had to be carefully screened and evaluated because of the inferior quality of their products. In this evaluation, the Medical Department Board was assisted by the Council on Physical Therapy of the American Medical Association and the directors of physical therapy departments in Army general hospitals.

32Smith, Clarence McKittrick: The Medical Department: Hospitalization and Evacuation, Zone of Interior. United States Army in World War II. The Technical Services. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1956, p. 6.

![]()