AMEDD Corps History > Medical Specialist > Publication

Occupational Therapists Before World War II (1917-40)1

Lieutenant Colonel Myra L. McDaniel, USA (Ret.)

Section I. World War I

The use of activity in the treatment of patients had been a part of civilian hospital programs long before World War I. Remedial work had been used in the United States since the early 1800`s in treating mental patients and since the early 1900`s in reeducating handicapped persons.2 During this period, the philosophy regarding the industrial cripple had changed both in the United States and abroad. Formerly, the crippled and disabled had been supported by charity or philanthropy. Gradually, it was recognized that it would be wiser to try to equip these people with skills which would enable them to become both socially and industrially effective. This new concept of reeducation became the foundation of the Medical Department reconstruction programs for the wounded and mentally ill soldiers of World War I.

Each country engaged in the war had evolved its own reconstruction program aimed at returning the disabled soldier to duty, or if that was not possible, at preparing him to earn a living. In the spring of 1917, under the direction of Maj. Gen. William Crawford Gorgas, The Surgeon General, neuropsychiatrists, and orthopedic surgeons visited England, France, and Canada to study the reconstruction programs in those countries. They learned about many reconstruction problems, one of the most formidable to the neuropsychiatrists being the diagnosis and treatment of war neuroses.

On 6 April 1917, the United States declared war against Germany. The time to develop an Army reconstruction program had come and existing facilities were far from adequate. It was decided that a central division of reconstruction should be created, and special reconstruction hospitals should be designated in which the work of all departments could be correlated. Because of the emphasis placed upon occupation in the reconstruction programs of other countries, and because of the effectiveness of patient activity in civilian institutions in this country,

1Unless otherwise indicated, primary sources of information for this chapter are: (1) The Medical Department of the United States Army in the World War. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1927, vol. XIII. (2) The Medical Department of the United States Army in the World War. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1929, vol. X.

2Letter, Maj. Thomas W. Salmon, MRC, Division of Neurology and Psychiatry, Office of the Surgeon General, to Maj. C. L. Furbush, Executive Officer, Office of the Surgeon General, 5 Nov. 1917, subject: Training of Occupational Teachers for Reconstruction Hospital.

70

occupational therapy became a basic part of the reconstruction program.

On 22 August 1917, in the Surgeon General`s Office, the Division of Special Hospitals and Physical Reconstruction was formed to coordinate the treatment and training of sick and wounded soldiers here and abroad and to secure employment for them when they were discharged. Maj. (later Brig. Gen.) Edgar King, MC, was assigned as chief of the division.3

The initial program, particularly the plans for placement of the retrained patients, proved to be too elaborate and was disapproved by the War Department. At this point, The Surgeon General of the Army called a conference of government and civilian organizations interested in reconstruction and rehabilitation problems. As a result of this conference, the separate functions of military, civilian, and government agencies were outlined. The Surgeons General of the Army and Navy were to be responsible for reconstruction and rehabilitation until the soldier or sailor was ready for discharge. Then civilian or other government agencies would continue the program. The War Department approved this arrangement on 31 July 1918.

In May 1918, the functions of the division were more clearly defined and the name was changed to the Division of Physical Reconstruction. Its intent was, through the use of mental and manual work, to restore to complete or maximum possible function, any military person disabled in line of duty. Every military person was entitled to this service prior to his discharge.

The first Supervisor of Reconstruction Aides in Occupational Therapy and Physical Therapy was Miss Marguerite Sanderson who had worked for several years with the well-known orthopedic surgeon, Dr. (later Col.) Joel E. Goldthwait of Boston, Mass. Miss Sanderson was appointed in January 1918 and assigned to the Division of Orthopedic Surgery, Surgeon General`s Office. Her primary duty apparently was to recruit and arrange for training of personnel for these programs. Records indicate that medical officers in the Divisions of Orthopedic Surgery and Neurology and Psychiatry planned the scope of the treatment programs and detailed the functions of the aides. In May 1918, Miss Sanderson and the reconstruction aide program were transferred to the Division of Physical Reconstruction.

The classification "reconstruction aide in occupational therapy" included four types of personnel: teachers of crafts, teachers of academic

3Assigned to the Division of Special Hospitals and Physical Reconstruction were representatives of the division of head surgery and the division of neuropsychiatry and psychology; a surgical adviser, technical advisers in the areas of commercial, professional, industrial, and agricultural education; an officer to abstract literature on reconstruction and reeducation; an officer concerned with educational propaganda; and three architects. (See footnote 1 (1), p. 69.)

71

subjects, medical social workers, and office workers.4 Inasmuch as this chapter records the history of those who were primarily concerned with craft activity, their subsequent title "occupational therapy aide" will be used throughout the chapter.

Early in 1918, the reconstruction program began operation. Official specifications for the work of occupational therapy aides, as drawn up by the Division of Physical Reconstruction and approved by The Surgeon General, 5 January 1918, required that it be a purely medical function for the therapeutic benefit of activity, and prescribed in early stages of convalescence.

Instructions published by the Surgeon General`s Office in March 1918 classified all therapeutic work except physical therapy as occupational therapy and divided it into two types: ward occupations or shop and farm work. In either case, medical officers selected the patients who were to participate. These instructions also provided that reconstruction hospitals were to have an educational officer in charge of assigning aides and patients within the program. Occupational therapy aides were generally assigned to work with patients on the wards. The trade and agricultural occupations were taught by male instructors who also supervised the curative workshop activities.

Qualifications

The task of selecting people to serve as occupational therapy aides was difficult, probably because no standards of training or education existed. The criteria for selection as finally determined were similar, insofar as age and physical and educational qualification, to those of the Army Nurse Corps and were evidently determined with an eye toward future equality of status and pay.

From records and correspondence we learn that high qualities of character and skill in handicrafts were the chief early requirements. Many of those selected early in the program had extensive art training and their knowledge of anatomy proved to be an asset to them, particularly when orthopedic surgeons discussed the disabilities of their patients and the bone and muscle involvements which resulted. However, the need for aides with varying qualifications was anticipated:

"* * * it seems very probable that we will have to have two classes of aides, one * * * to perform the work as now outlined, and the second * * * more qualified medically * * * to handle * * * the nervous and mental cases."5

The earliest recorded list of qualifications stated:6

4Letter, Maj. M. E. Haggerty, SC, Division of Reconstruction, Office of The Surgeon General, to Miss Marion C. Prentice, Director, Illinois School for Nurses, Social Service Department, Chicago, Ill., 18 Jan. 1919.

5Letter, Maj. H. R. Hayes, SC, Division of Orthopedic Surgery, Office of The Surgeon General, to Mrs. Martha Wadsworth, Avon, N.Y., 10 Mar. 1918.

6Information Circular B-524, signed by Col. Frank Billings, MC, Office of The Surgeon General.

72

The qualifications * * * are in the main those of good teachers: knowledge and skill in the * * * occupation to be taught, attractive and forceful personality, teaching ability, sympathy, tact, judgment, [and] industry.

Not until June 1918 was hospital experience made a required part of preliminary training.7

Other prerequisites were: U.S. citizenship, 25-40 years of age, 60-70 inches in height, 100-195 pounds in weight, and ability to pass the physical examination required of members of the Army Nurse Corps. Applications were accepted from both single and married women. The latter group were to be assigned primarily in the United States.

Even though emergency courses were established for the training of occupational therapy aides, attendance at these courses was not required if an applicant was either a trained craftworker or a graduate of a school of industrial arts and crafts.8 By August 1918, the equivalent of graduation from a secondary school was required and preference was given to normal school and college graduates with comparable technical training.

Selection, Appointment, and Assignment

In addition to the graduates of the training courses, the Army had three major sources of applicants for occupational therapy aide positions: volunteers recruited by private organizations for work with blinded soldiers in England and France, the National Society for the Promotion of Occupational Therapy, and the American National Red Cross.

Applicants were selected as occupational therapy aides by the Surgeon General`s Office.9 Letters of appointment, equivalent to contracts of employment, were given at the time the occupational therapy aides took their oaths of office; these were explicit concerning salary, maintenance, and provision for transportation and per diem while traveling. Appointments were for the duration of the war and for any further time that The Surgeon General thought their services were required.

Aides were assigned to specific hospitals or sent overseas in either a hospital unit or in a unit of aides for reassignment. There were two classes of occupational therapy aides; they worked with patients with orthopedic conditions or with war neuroses. Early in the program there was no established patient/therapist ratio, but in July 1918, tentative

7Letter, Marguerite Sanderson, Supervisor, Reconstruction Aides, Office of The Surgeon General, to Professor T. W. Burckhalter, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pa., 12 June 1918.

8Letter, Marguerite Sanderson, Supervisor, Reconstruction Aides, Office of The Surgeon General, to Mrs. Anne Franklin, The Delineator, Butterick Building, New York, N.Y., 21 May 1918.

9In many instances early in the program`s inception, candidates were screened by Mrs. Martha Wadsworth, Avon, N.Y., who had previous experience in obtaining volunteers from Junior League and other sources for work overseas with blinded soldiers. It was believed that screening by one person would assure high standards. She held personal interviews with candidates and checked personal and character references before recommending any applicant to the Surgeon General`s Office for appointment. Mrs. Wadsworth functioned officially as a member of an advisory committee of the Division of Orthopedic Surgery, Surgeon General`s Office.

73

73

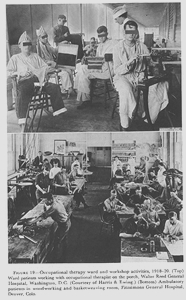

FIGURE 19. Occupational therapy ward and workshop activities, 1918-20. (Top) Ward patients working with occupational therapist on the porch, Walter Reed General Hospital, Washington, D.C. (Courtesy of Harris & Ewing.) (Bottom) Ambulatory patients in woodworking and basket weaving room, Fitzsimons General Hospital, Denver, Colo.

74

approval was given the ratio of 2 occupational therapy aides for each 50 patients.10

Duties

By May 1918, it had been clarified that the function of occupational therapy aides was to teach crafts on the wards to patients who had impaired motor function or who were neurotic or mentally disoriented. Gradually, the occupational therapy aides also assumed responsibility for curative workshop activities in the treatment of ambulatory patients

(fig. 19), taking over this function from enlisted personnel and male civilian instructors who had been concerned with vocational training but not medical treatment.11 The Army emphasis on vocational training began to slacken in June 1919 when an amendment to the Smith-Hughes Act of 1917 placed the entire responsibility (selection, training, and payment) for the rehabilitation of disabled soldiers upon the Federal Board for Vocational Education.

Classification and Salaries

Occupational therapy personnel were classified in two grades: aides and head aides. The beginning salary for aides was $50 per month, and $65 the salary for head aides. Meals, lodging, and laundry were furnished, but when lodging and meals were not available, an additional $62.50 per month was allowed. When serving overseas, they received an additional $10 per month. Travel allowances covered transportation costs and $4 per diem.

Uniforms

The uniforms worn by occupational therapy aides both in the United States and overseas were similar to those worn by the physical therapists except that white bib aprons were authorized for the occupational therapy aides as a part of their hospital uniforms.

Basic clothing items, with the exception of the street uniforms, were supplied by the Red Cross without cost to each aide going overseas. Among these items were a raincoat, rubber boots, woolen underwear, outing flannel pajamas, woolen stockings, cotton stockings, woolen tights, one black and two tan pairs of shoes, and three hospital uniforms. The street uniform was purchased at cost through the Red Cross.12

In October 1917, Dr. Franklin Martin of the Council for National

10Letter, Col. Frank Billings, MC, Division of Reconstruction, to The Surgeon General, 2 July 1918, subject: The Assignment of Reconstruction Aides in Occupational Therapy and Physio-therapy to General Hospitals Functioning in Physical Reconstruction.

11The ratio of occupational therapy aides to workshop instructors at Walter Reed General Hospital changed from 39 aides to 6 workshop instructors in 1923 to 16 aides to 1 workshop instructor in 1932.

12Form C-428, Instructions for Reconstruction Aides, Overseas Service, Office of The Surgeon General.

75

Defense wrote to William Rush Dunton, Jr., M.D., president of the National Society for the Promotion of Occupational Therapy, requesting information on colleges or schools giving courses of instruction in occupational therapy.13 Doctor Dunton replied that he knew of only two colleges (Teachers College, Columbia University, New York, N.Y., and Simmons College, Boston, Mass.) which were offering these, but he believed there were a number of courses being given in institutions throughout the country. On 26 November 1917, Dr. Dunton wrote to 54 hospitals and schools to gather further information. His first question was, "How much time in your nurses` training course is given to occupational therapy?" Of the 34 replies received (29 hospitals, 1 course conducted by the Red Cross, and 4 schools), 16 stated that no course in occupational therapy was offered and the remainder gave information on courses which ranged from 3 to 48 hours.

The Surgeon General`s Office, however, was to emphasize courses specifically for occupational therapy aides and divorce this training from nurses` training programs. In January 1918, a basic outline was proposed by the Surgeon General`s Office for guidance of any organization which wished to establish emergency training programs.

Outline of basic 10-week course, January 1918:1 | Hours |

|

Weaving | 49 |

|

Wood carving | 49 |

|

Woodworking | 30 |

|

Basketry | 30 |

|

Pasteboard construction and elementary bookbinding | 30 |

|

Leatherworking | 30 |

|

Incidentals (rugmaking, modeling, netting, knitting or crocheting, stenciling, and beadwork) | 43 |

|

Design | 49 |

|

Total | 310 |

|

Hospital routine | 7 |

|

Invalid teaching | 26 |

|

Practice work | 42 |

|

Total | 75 |

|

Grand Total | 385 |

1Letter, Mrs. Martha Wadsworth, Avon, N.Y., to Maj. Henry R. Hayes, SC, Division of Orthopedic Surgery, Office of The Surgeon General, 2 Feb. 1918, with enclosure, subject: Suggestions for School Course for Occupational Aides Based on Tentative Outline Made at Conference, January 28th, 1918. Early in 1918, Mrs. Wadsworth had been designated by the Surgeon General`s Office to screen all candidates for appointments as occupational therapy aides. As a representative of the Surgeon General`s Office, she was also consulted on curriculum content.

It soon became apparent that knowledge of crafts would have to be supplemented by medical lectures and hospital practice, and in September 1918, a more complete course was proposed.

13These courses were not called occupational therapy courses, but had names such as invalid occupations, occupation treatment for nurses, or bedside occupations.

76

Outline of revised course, 12-16 weeks, September 1918:1 | Hours |

|

Handcrafts: Weaving | 39 |

|

Chair caning or rush seating | 12 |

|

Woodworking | 45 |

|

Basketry | 36 |

|

Bookbinding | 15 |

|

Block printing | 6 |

|

Metal (tin and copper work) | 24 |

|

Cordworking | 12 |

|

Rugmaking | 9 |

|

Modeling | 15 |

|

Design | 51 |

|

Total | 264 |

|

Lectures: History, principles, and purpose of occupational therapy | 3 |

|

Principal methods of teaching | 9 |

|

Elementary applied psychology | 12 |

|

Special problems of the handicapped | 11 |

|

Disorders of central nervous system | 5 |

|

Maladjustments | 1 |

|

Kinesiology | 5 |

|

Hospital routine etiquette | 2 |

|

Conferences and discussion | 16 |

|

Total | 64 |

|

Hospital practice | 264 |

|

Total | 592 |

1Letter, Susan C. Johnson, Director, Training Course for Teachers of Occupational Therapy, Columbia University, New York, N.Y., to Dean James E. Russell, Education Department, Division of Reconstruction, Office of The Surgeon General, 30 Sept. 1919.

Several emergency training programs were established early in 1918 under certification of the Surgeon General`s Office.14 These included the Boston School of Occupational Therapy, Boston, Mass. (Mrs. Joel E. Goldthwait, Chairman), Training Course for Teachers of Occupational Therapy, Teachers College, Columbia University (Miss Susan C. Johnson, Director), and War Services Classes, New York, N.Y. (Mrs. Howard Mansfield, Chairman). By June 1918, certification was dropped because the estimated number of occupational therapy aides needed was modified from 1,000 to 300.

The qualifications for admission to an occupational therapy course in 1918 were quite general: at least 23 years of age, U.S. (or allied country) citizenship, a suitable personality, some artistic or mechanical skill, and willingness to serve full time during the war emergency.

The courses conducted in civilian institutions varied in length from an 8 weeks` emergency program, for those already proficient in some craft, to an 8 months` program.15 Credit was sometimes given for previous medical or craft experience, and in some instances, students, on their own initiative, stayed in the hospital practice phase beyond the required time.

14Prospectus, Boston School of Occupational Therapy, Boston, Mass., 1918.

15Prospectus, Philadelphia School of Occupational Therapy, Philadelphia, Pa., 1918.

77

Occupational therapy in the Medical Department began as a very limited and experimental program on the orthopedic wards at Walter Reed General Hospital, Washington, D.C., in February 1918. Col. Elliot G. Brackett, MC, Chief, Division of Orthopedic Surgery, Surgeon General`s Office, initiated the program with three occupational therapy aides under the direction of Maj. Thomas M. Foley, MC, Chief, Orthopedic Service, Walter Reed General Hospital. At that time, no official funds were provided to support this program nor was it clear where this service should be placed in the hospital organizational structure. By May 1918, reconstruction programs in Army general hospitals had been started at Fort McHenry, Md., Fort McPherson, Ga., and Lakewood, N.J. By July, 21 additional hospitals were designated to participate in the program.

Although the impetus for initiating occupational therapy in Army hospitals came from orthopedic surgeons and neuropsychiatrists, it, unlike physical therapy, was placed organizationally under the education section, perhaps because many aides had come from the teaching field. By July 1919, directors of reconstruction programs were assigned to the reconstruction hospitals, and both components of the reconstruction programs (education service and physical therapy) were placed under their direction.

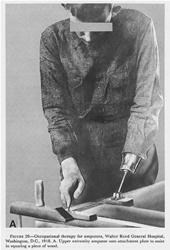

Amputations

The Army furnished only provisional artificial limbs to the disabled soldier who, after discharge, obtained his permanent limb (s) from the Bureau of War Risk Insurance. The use of provisional appliances made possible immediate fittings and early corrections of stump defects, and enabled surgical, prosthetic, physical therapy, and, most important, reeducation programs to be coordinated (fig. 20). Also, the patient had time to learn about appliances before making his final choice.

Occupational therapy aides worked with upper extremity amputees both before and after they had obtained their artificial limbs. Strap attachments above the stump were so contrived that eating utensils, paint brushes, and tools could be used until the artificial limb was available. Emphasis was placed on strengthening muscles above the site of amputation and on regaining proficiency in the use of the extremity.

The first upper extremity appliances were simple in design and fabrication. The socket was plaster of paris with a metal clamp attachment with which implements could be held. Later, an inexpensive arm was fabricated with a universal end-attachment plate in which a hand, a tool, or a hook could be fastened. Occupational therapy`s goal was to enable the patient to gain maximum use and control of the appliance.

78

78

FIGURE 20. Occupational therapy for amputees, Walter Reed General Hospital, Washington, D.C., 1918. A. Upper extremity amputee uses attachment plate to assist in squaring a piece of wood.

79

79

FIGURE 20. Continued. B. Lower extremity amputee working on handmade wood lathe in treatment program. (U.S. Army photograph.)

80

Blindness

The occupational therapy program at General Hospital No. 7, Roland Park, Md., the only blind treatment center, was directed toward alleviating two major problems of newly blinded soldiers: Adjustment to loss of eyesight and limitation of physical activity. The work was complicated by the hostility and discouragement of patients who had been misled, by uninformed persons, into thinking they would encounter golden opportunities to earn great sums of money and would be almost unrestricted in the things they could do.

The reconstruction program was a practical one, aimed mainly at increasing the patients` manual dexterity. It included manual training, typing, vocational instruction, reading and writing Braille, and academic courses. In some areas, this original program was too optimistic as to the ability of the blind to compete with the nonblinded. It was being modified when the Army decided to discharge blind patients and transfer them to the jurisdiction of the Red Cross for further rehabilitation.

Head and Nerve Injuries

In neurological complications resulting from either head or nerve injuries, occupational therapy provided active exercise for muscles recovering from paralysis and aided greatly in reducing fibrosis of the small joints following interference with nerve function. As voluntary movements improved and endurance increased, exercise was directed toward timing and accuracy and patients were assigned to specialized activities in the curative workshops.

Neuropsychiatric Conditions

When the question of occupational therapy in neuropsychiatric hospitals was first considered, the feasibility of introducing such procedures generally into the neuropsychiatric wards was doubted. Occupational therapy was thought to be applicable only to those cases which were less disturbed mentally. This opinion changed in a few months, however, as the aides increased their skill and the benefits of occupational therapy became clearer.

Neuropsychiatric patients were separated from other classes of disabled, and, in addition, men with war neuroses were separated from those with functional disorders because the latter would require more individual attention in vocational training. Also, it had been found that men with war neuroses were inclined to be faultfinders and troublemakers and a few could corrupt general morale and make vocational training particularly difficult.

The war produced some substantial changes in the care of neuropsychiatric patients. As their number increased, active treatment replaced custodial care, individualization was stressed, and diagnosis was

81

no longer considered an end in itself. With the decrease of physical restrictions and, in some places, their complete removal, the climate became that of a hospital, rather than a jail.

Occupational therapy in the neuropsychiatric sections had an independent and important place under the immediate direction of the psychiatrist. Reports of the beneficial results of occupational therapy applied to neuropsychiatric patients are found in the histories of several of the general hospitals. A few extracts illustrate the aspects of the work commented upon:

In 1919, the commanding officer, Fort Sam Houston Station Hospital, Tex., reported:

Prior to the establishment of this work among the mental and nervous cases of this hospital it was practically impossible to avoid placing the patients who were in the department in an enforced state of idleness. It is a natural consequence that idle insane patients are prone to continual self-analysis and elaboration of delusions. Likewise, unoccupied, the cases of precocious dementia are very prone to mental deterioration. With the advent of the industrial pursuits and the presence of the reconstruction aides in daily attendance among the patients, there is a noticeable improvement, a lessened tendency toward excitement or seclusiveness.

The following is taken from the account of the neuropsychiatric activities at General Hospital No. 2, Fort McHenry, for 1917-20:

In the treatment of nervous and mental disorders occupation and recreation were of paramount importance. An occupational aide who had the happy faculty of exciting interest in a catatonic praecox, of arousing the interest of a patient in the depressed phase of a manic-depressive psychosis, of directing to useful and constructive channels the hyperactivity of a maniac, or who might be able to replace the obsessive idea of a psychasthenic with a healthy, helpful, and interested thought, certainly accomplished a great deal toward the recovery of such a patient.

Osteomyelitis

For patients with osteomyelitis, occupational therapy was prescribed to restore or improve function of stiffened joints. As the patient became engrossed in a project, he would actively exercise the contracted muscles and stiffened joints. Activities to involve use of the upper extremity appear to have had major emphasis, and included metalworking, woodworking, toymaking, and weaving.

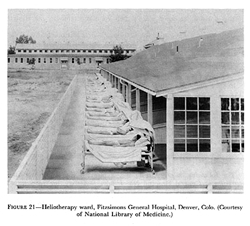

Pulmonary Tuberculosis

Bed rest, climate, and heliotherapy were key factors in the treatment of tuberculous patients (fig. 21). For this reason, reconstruction programs for these patients developed very gradually. During the febrile stage of the disease, all unnecessary exertion was contraindicated. Although it was obvious that these long-term patients became discontented and very restless, chiefs of medical services in several hos-

82

82

FIGURE 21. Heliotherapy ward, Fitzsimons General Hospital, Denver, Colo. (Courtesy of National Library of Medicine.)

pitals actively opposed adoption of an activities program even after it had been made mandatory by The Surgeon General.16

Six hospitals were originally designated for treatment of tuberculous patients, but by October 1919, this number was cut to two--General Hospitals No. 19, Oteen, N.C., and No. 21, Denver, Colo.

Patients were divided into three classes:

1. Bed patients (very little activity).

2. Ambulatory patients (mild exertion, prescribed rest periods).

3. Patients with inactive tuberculosis (gradual increase of routine to full day`s activity).

These classes were generally subdivided further by the hospitals to provide a means for more accurate scheduling of the patient`s daily routine.

Occupational therapy programs in tuberculosis hospitals consisted mainly of ward occupations, academic work, and some curative work-

16One chief of a medical service thought tuberculous patients should not be permitted to take exercise in any form (General Hospital No. 21 , Denver, Colo.). Another considered mental work deleterious (General Hospital No. 8, Otisville, N.Y). Another could see no good feature in any variety of reconstruction activity (General Hospital, Fort Bayard, N. Mex.). History indicates that those who continued to oppose the policy and program as appoved by The Surgeon General were transferred to other medical fields of activity. (See footnote 1 (1), p. 69.)

83

shop activities.17 Shop courses were seldom used because patients well enough to participate usually demanded a discharge. Certain hospital activities--for example, laundry, kitchen, bakery, printshop, usually included in curative workshop schedules--were considered inappropriate for tuberculous patients because the work was too confining, there was danger of infecting others, or the work schedule was too demanding.

Materiel Problems

Occupational therapy programs encountered some early difficulties. One, described in the Walter Reed General Hospital report to The Surgeon General for 1918, was lack of funds for supplies and equipment: The original $3,000 authorized by The Surgeon General for this hospital was not adequate. Base hospitals experienced the same problem. In the crisis, the Red Cross placed $200 per month for supplies and equipment at the disposal of each hospital having a reconstruction program. By May 1919, adequate finances were generally available.

In addition, there were problems related to the disposition of articles made in occupational therapy. At first there were no restrictions, but too many patients began spending too much time making articles to sell, rather than taking advantage of available educational courses. Instructions issued from the Surgeon General`s Office in October 1918 stated that materials for articles having sale value would be purchased through the hospital fund, the articles would be sold through the post exchanges or other sources, and the price of the materials returned to the hospital fund afterward. These rules tended to discourage commercialism among the patients. Tuberculous patients were permitted exceptions to the rules, however, because producing salable articles tended to increase their confidence in their ability to become self-supporting. This was an important morale factor.

The first American troops reached France on 25 June 1917. Before the end of the war, more than 2 million men were sent there, creating tremendous problems in logistical support. Equipment for many of the occupational therapists with the American Expeditionary Forces had to be improvised or obtained locally. No records are available to indicate the total number of occupational therapy aides assigned; that they were there and that they were effective is borne out in reports of hospital activities during this period. On 16 June 1918, the first occupational therapy aides arrived overseas with Base Hospital No. 117, La Fauche, France, a neuropsychiatric unit. The second group arrived

17A comprehensive description of the reconstruction program for tuberculous patients can be found in The Medical Department of the United States Army in the World War. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1927, vol. XIII, pp. 189-202.

84

84

FIGURE 22. Occupational therapy aides, Evacuation Hospital No. 27, army of occupation, Coblenz, Germany. (Courtesy of National Library of Medicine.)

on 13 August 1918 and were initially assigned to work with orthopedic patients at Base Hospital No. 9, Chateauroux, France. As of May 1919, there were 55 occupational therapy aides with the American Expeditionary Forces, 17 of whom were stationed in Germany with the Third U.S. Army (fig. 22).

Patients most often treated by occupational therapy aides were those with orthopedic injuries and neuropsychiatric disorders whose conditions were such that a return to combat or other oversea duty was anticipated. Patients whose condition would prohibit further duty overseas were evacuated to the United States.

In July 1918, Colonel Goldthwait, Chief Consultant in Orthopedic Surgery, American Expeditionary Forces, stressed the need for a large number of aides trained in bedside occupation. As a result, Gen. John J. Pershing recommended to the War Department, on 2 August 1918,

85

that 10 occupational therapy aides accompany each base hospital sent overseas and be reassigned after their arrival.18

Col. Thomas W. Salmon, MC, Senior Consultant in Neuropsychiatry, American Expeditionary Forces, in an August 1918 letter, wrote enthusiastically about the work of the occupational therapy aides at Base Hospital No. 117:19

The Reconstruction Aides, especially those working in handicrafts, are worth their weight in gold. I could use 20 of that type in the A.E.F. today to the best advantage. Perhaps I could use some of the "highbrow" type, but I am not sure. At any rate, if the amount of cubic feet which they will occupy on the voyage has to be considered, send me those trained with the feebleminded, who have industry, optimism and bright, receptive minds.

As a consequence of that letter, occupational therapy aides sent overseas for work with neuropsychiatric patients were required to have previous experience in working with the mentally ill and be skilled in bedside occupations.

Status

In the beginning, there was no aura of distinction about being an occupational therapy aide. Except for those assigned with the neuropsychiatric hospital units, the early status of the aide was that of an unknown entity. Few people knew what the aides were supposed to do. They were civilians in a military setting, and they were a new professional group with the Army. It was an understandable situation, in retrospect, since the term "occupational therapy" had only been in use since 1917, and there had been insufficient time for the aides to earn stature and recognition through professional accomplishment. One aide reported, "We were nondescripts. We were pioneers going out with hardly the military status of scrubwomen."20

In several hospitals, until their duties were clarified, the occupational therapy aides assisted the nurses. Miss Lena Hitchcock, occupational therapy aide, assigned to Base Hospital No. 9, comments as follows on her nurses` aide activities:21

I went on duty at 6 a.m., and until 9 a.m. did nurses` aide work (administered Dakin`s solution to all patients receiving the treatment, swept out 70 beds with a whiskbroom, washed 70 faces and prepared 4 dressing carts (assisting at one), did all sterilizing). Lunched from 11:30 a.m. to 12 m., back to the ward until 6 p.m., interrupted by supper at 5 p.m. (½ hour), * * * time spent from 6 to 8 p.m. as nurses aide as well as three Sundays per month.

Even after the occupational therapy programs were organized, these were sometimes halted temporarily so that the aides could assist the

18Cablegram, Gen. John J. Pershing to The Adjutant General, Washington, 2 Aug. 1918, par. 9.

19Letter, Maj. Frankwood D. Williams, MC, Division of Neurology and Psychiatry, Office of The Surgeon General, to Mrs. Howard Mansfield, New York, N.Y., 19 Aug. 1918.

20Hoppin, Laura Brackett: History of the World War Reconstruction Aides. Millbrook, N.Y.: William Tyldsley, p. 76.

21Personal correspondence of Miss Lena Hitchcock, Reconstruction Aide in Occupational Therapy in World War I, with the author.

86

nurses when large convoys of sick or wounded soldiers arrived. This was particularly evident during emergency periods in the fall of 1918 when all hospital activity was focused on caring for the influenza patients from the transports and the wounded from the Meuse-Argonne Campaign which lasted from 26 September to 11 November 1918.

In November 1918, the occupational therapy aide`s role as a nursing assistant was made official: "* * * when their services are not required in their special work they may be temporarily assigned to duty as nurses` aides.``22

Orthopedic Programs

The accounts of the occupational therapy programs for orthopedic patients at Base Hospital No. 9 and Base Hospital No. 8, Savenay, France, are representative both in problems encountered and work accomplished.

Since the occupational therapy aides had been sent to France with no supplies or equipment, they used their own funds and imagination to supply them. They salvaged empty tin cans and wooden boxes to begin their metalworking and woodworking programs. The ingenuity and enthusiasm of the aides were infectious and the wounded soldiers themselves soon saw possibilities for materials for projects. Shell casings were their major contribution. These came in all sizes and were extremely popular as they provided a source of brass of different thicknesses for projects which could be graded in size and difficulty according to the treatment needs of the patient.

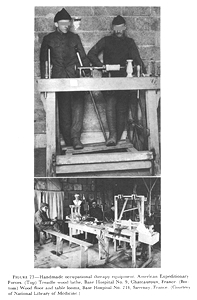

As for equipment, an almost destitute situation prevailed in both hospitals. Base Hospital No. 8 started with one chest of tools, while Base Hospital No. 9 began its occupational therapy programs with one claw hammer and an old, fancy French plane. Later, both hospitals accumulated lathes, saws, and drills, and aides and patients built looms and other necessary equipment (fig. 23).

Orthopedic surgeons examined the patients and recommended activities for them. The diagnostic categories included fractures, gunshot wounds, peripheral nerve injuries, and amputations. The objectives of treatment were twofold: (1) Psychological--to have the patient recognize his abilities and to divert his attention from his disabilities; (2) physiological--to maintain and improve function of the injured part or, in the case of upper extremity amputation, to work toward skilled and dexterious use of the remaining extremity.

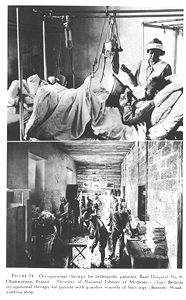

These objectives were met through distinct programs for bed and ambulatory patients (fig. 24), as follows:

Bed patients.-Activity requiring little physical effort but much concentration and coordination: woodcarving, leatherwork, blockprinting, simple weaving, and knitting.

Ambulatory patients.-As soon as possible, patients with upper ex-

22Circular No. 56, American Expeditionary Forces, 19 Nov. 1918.

87

87

FIGURE 23. Handmade occupational therapy equipment, American Expeditionary Forces. (Top) Treadle wood lathe, Base Hospital No. 9, Chateauroux, France. (Bottom) Wood floor and table looms, Base Hospital No. 214, Savenay, France. (Courtesy of National Library of Medicine.)

88

88

FIGURE 24. Occupational therapy for orthopedic patients, Base Hospital No. 9, Chateauroux, France. (Courtesy of National Library of Medicine.) (Top) Bedside occupational therapy for patient with gunshot wounds of both legs. (Bottom) Woodworking shop.

89

tremity injuries to be engaged in light activity (light brasswork, woodcarving, and general carpentry) to maintain muscle tone and to prevent stiffness and atrophy. Hand drills were used to improve and strengthen grasp. Men unable to grasp wore gloves which could be tied to the handle of the tool to achieve a beginning pattern of motion. Sawing was considered the best exercise for shoulder conditions. Metal hammering on lightweight brass provided flexion and extension for wrist problems. Patients with lower extremity injuries used looms, saws, and drills to increase strength and range of motion or did workbench projects to increase standing endurance and strength.

Approximately 2,400 upper extremity amputees were returned to the United States.23 Very little was written about the occupational therapy program for amputees, although reports from Base Hospital No. 9 indicate early attempts in retraining because of loss of the dominant hand or arm.

Neuropsychiatric Programs

Neuropsychiatric service with the American Expeditionary Forces was begun in December 1917, when Colonel Salmon was appointed director of psychiatry. The most urgent problems he faced were (1) to provide psychiatric service to troops in the field and (2) to establish a special hospital for the treatment of men with war neuroses who were appearing in increasing numbers in base hospitals. A neuropsychiatrist was assigned to each combat division to handle the first problem. By February 1918, a special hospital had been selected at La Fauche and 16 base hospitals were receiving or ready to receive neuropsychiatric patients. Later, a special neuropsychiatric hospital was established at a base port to facilitate evacuation to the United States.24

By the time the United States entered World War I, new methods of combat--high explosives, liquid fire, tanks, poison gas, bombing planes, trench warfare--had created a novel entity called shellshock. There was some controversy as to whether the cause was mental or physical, but the condition gradually became recognized as a functional war neurosis. It usually occurred in unwounded soldiers. Since shell explosives were seldom a factor in the onset of the condition, an attempt was made to abolish the term "shellshock" but its popularity prevailed, particularly among the troops.

The functional war neuroses25 were the only group of neuropsychiatric patients to be treated with the direct objective of return to

23The Medical Department of the United States Army in the World War. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1927, vol. XI, pt. 1, p. 718.

24Evacuation was not easily accomplished. No special vessels were designated for the transportation of neuropsychiatric patients and they had to be included in the limited hospital accommodations available on the return trips. There was misunderstanding as to what constituted proper accommodations for these patients, and, as a result, some were retained in the port hospital while other sick and wounded were more rapidly evacuated. Treatment programs were continued during this period so that there was no gap in the care of these patients.

25The following conditions were classified as war neuroses: Neurasthenia, hypochondriasis, hysteria, anxiety neurosis, anticipation neuroses, effort syndrome, exhaustion, timorousness, and gas and concussion syndrome.

90

duty with the American Expeditionary Forces. Other neuropsychiatric patients (psychoses, mental deficiency, constitutional psychopathic states) were returned to the United States.

The number of neuropsychiatric hospitals to which occupational therapy aides were assigned is not known, but the program at Base Hospital No. 117, which was the treatment center for functional war neuroses, appears representative of occupational therapy activity. A study of British and French management of patients with war neuroses disclosed that early treatment prevented loss of effective manpower. Base Hospital No. 117, operating on this principle, was most successful, returning 50 percent of these patients to combat and 40 percent to other military duty.

Equipment, supplies, and space were available for occupational therapy at Base Hospital No. 117 since this unit had been planned and organized in the United States; thus, some of the problems which confronted the orthopedic programs were not present. Money and credit were given by the National Committee on Mental Hygiene and, as supplies diminished through use, by the Red Cross.

One of the basic treatment principles was that work was one of the most important parts of symptomatic cure. More than 80 percent of the patients were always working--in the fields, building roads, chopping wood, or in the workshop. Work selected was always of a type that would provide tangible proof of effort.

Meta Anderson, occupational therapy aide, in her report of activities at Base Hospital No. 117, comments on the work scheme as follows:

From early in June until the end of the war nearly 3,000 cases of war neurosis passed through the hospital. A large proportion of these took part in some kind of work in the workshop as part of their treatment. It was possible to judge, therefore, with a fair approach to accuracy, just what this sort of work was able to do for them, and how necessary a part of the hospital for the neuroses is a workshop.

* * * * * * *

The workshop was considered a sort of specialized therapy directed to a more definite end, planned to treat some definite symptom or to meet some special indication, while the other work was regarded as a kind of therapeutic background underlying the whole scheme of curative effort. The physiological and psychological needs were met by the use of muscular effort in the production of tangible articles. The handling of the tools and the various movements of sawing, nailing, screwing, and hammering, and the finer and more coordinated movements of wood carving, metal work of various kinds, weaving, and tinning, as well as much more delicate and more emotionally inspired technique of painting, sketching, and printing, supplied the essential training that the paralysis, tremors, and other symptoms needed.

Occupational therapy was carried out experimentally in a neuropsychiatric hospital in the forward area. The experiment lasted only 2 weeks but the medical officer in charge indicated that, through the assistance of workshop treatment, men were returned to duty who had previously been listed for evacuation to base hospitals for further treatment.

91

In service Educational Programs

During the winter of 1918-19, regular courses in psychiatry and neurology were given to hospital personnel, including occupational therapy aides, at Base Hospital No. 117 and Base Hospital No. 214, Savenay, France. During the same period, lectures by various surgeons were given on orthopedic subjects to the aides at Base Hospital No. 8.

Section II. Peacetime

By July 1919, only 19 Army general hospitals in the United States remained in operation for the treatment of the war injured. Some hospitals had been turned over to the U.S. Public Health Service,26 others had reverted to base hospitals in which only the sick of the camp commands were treated, and some had been deactivated. By June 1921, only six general hospitals were in operation for the treatment of patients with serious chronic conditions and those requiring general hospital care.27

Because of the decreasing activities, physical reconstruction was discontinued as a division in the Surgeon General`s Office in June 1919 and became a section in the division of hospitals. Although a reconstruction service was maintained in all the general hospitals and at the Fort Sam Houston Station Hospital, close supervision of the work and personnel was not maintained by the Surgeon General`s Office. A general policy of decentralization gave greater responsibility for professional services to the commanding officer in the hospital.

The actual number of occupational therapy aides on duty during World War I is unknown. Mrs. Eleanor R. Wembridge, Supervisor, Occupational Therapy Reconstruction Aides, reported that on 1 January 1919 there were 455 aides in the service; 358 of these were on duty in the United States and 97 were on foreign duty.28 It has been estimated that 1,400 reconstruction aides were employed as of June 1919 in the United States but since this category could include physical therapists, teachers, and social workers, in addition to occupational therapy aides, the figure is vague insofar as the number of occupational therapy aides is concerned. In December 1926, the Surgeon General`s Office recommended that physical therapy and occupational therapy aides be designated as such, since the term "reconstruction aide" for

26Until the Veterans` Bureau (now Veterans` Administration) was established in 1921, all discharged servicemen could be treated in U.S. Public Health Service hospitals under the provisions of the Bureau of War Risk Insurance.

27Army and Navy General Hospital, Hot Springs, Ark.; William Beaumont General Hospital, El Paso, Tex. (newly constructed, received its first patients on 1 July 1921); Fitzsimons General Hospital, Denver, Colo.; Letterman General Hospital, San Francisco, Calif.; Walter Reed General Hospital, Washington, D.C.; Fort Sam Houston Station Hospital, Tex.

28Wembridge, Eleanor R.: Historical Sketch of the Work of the Occupational Aides in the Division of Physical Reconstruction.

92

both groups was confusing as it did not identify the activities for which they were employed.

The number of occupational therapists assigned to Army Hospitals decreased during the peacetime period, 1919-40. This decrease is most realistically illustrated by the Walter Reed General Hospital annual reports which show a cutback from 75 aides and 90 enlisted men in April 1919 to the discharge of all aides "without prejudice" in June 1933. The latter state resulted from an Army-wide reduction in force dictated by the National Economy Act of that year Although one occupational therapy aide was reemployed in October, she was paid from Civilian Conservation Corps funds for treatment of their members in the hospital. In 1939, two aides were on duty; one was paid from Medical and Hospital Department (Army) funds, the other from Civilian Conservation Corps funds.

The status of the occupational therapy aide was that of a civilian employee, Medical Department at Large. There were no provisions for retirement or disability compensation in that category, nor was there a graduated salary scale which would provide for regular salary increments. In June 1931, a graduated salary scale was adopted. Retirement and other benefits, however, were not provided until 1939 when all civilians paid from Medical and Hospital Department appropriated funds29 were brought under competitive civil service classification. The salary ranges throughout the peacetime period were very similar to those of the dietitians and the physical therapists. (See Appendix B, p. 595.) Aides continued to receive their appointment through the Surgeon General`s Office, and vacancies in Army hospitals were filled by graduates of the Army course while that course was in existence.

A 6 months` training course for occupational therapy aides was begun in October 1924 at Walter Reed General Hospital. The purpose of the course was to provide a source of skilled aides for assignment in Army hospitals. Limited to a class of 10 students, this course offered advanced training in occupational therapy, medical subjects, and practical experience in applying the work in military hospitals.

Application for admission was made directly to the Commandant, Army Medical Center, Washington, D.C. Applicants could not be less than 20 nor more than 30 years of age and, since this was an advanced course, they had to be graduates of schools which required at least the minimum standards for training courses in occupational therapy. It was considered desirable to have additional training in a college or university. A civilian physician`s health certificate was required even though the applicant`s final acceptance was not assured until she had

29During this period, salaries were paid from one of three sources: Medical and Hospital Department (Army) funds, Civilian Conservation Corps, or Veterans` Bureau funds paid to the specific Army hospital for treatment of Civilian Conservation Corps or Veterans` Bureau patients.

93

passed the physical examination at Walter Reed General Hospital. Certificates of character from two reputable persons were also required.

Quarters, rations, and laundry were provided by the hospital and the students received $5.00 per month while in the training program. Each was required to furnish the prescribed uniform: A blue gingham dress, white apron with straps, white collar and cuffs, and white oxfords with low rubber heels.

In order to provide increased practical experience in the treatment of patients, the course was lengthened from 6 to 8 months in 1931 and to 9 months in 1932. A comparison of the 6-month and 9-month curriculums is shown in table 4. A request in 1932 to lengthen the course to 11 months was disapproved for financial reasons.

Maj. James B. Montgomery, MC, chief of physical and occupational therapy, directed the course, assisted by Miss Alberta Montgomery, supervisor of the occupational therapy aides.30 Several subjects were taken with the students of the Army School of Nursing. Medical subjects were taught by medical officers, and anatomy and the orientation to physical therapy were given by Miss (later Col.) Emma E. Vogel, supervisor, physical therapists. The remaining subjects were taught by members of the occupational therapy staff.

Because of financial curtailments necessitated by the National Economy Act of 1933, this training program was discontinued with the graduating class of 1933.31 At that graduation, Maj. Gen. Robert U. Patterson, The Surgeon General, remarked:32

In conclusion I wish to express my great regret at the temporary restrictions placed upon these courses of training at this hospital. These teaching schools at the Army Medical Center will only be suspended until funds become available to continue the schools and pay the students.

Both the dietitian and physical therapist courses were resumed in 1934. Brig. Gen. Albert E. Truby, Commanding General, Army Medical Center, gave as his reason for not reopening the occupational therapy course, "Additional personnel would be required for instructors and it is not desired to increase the civilian personnel at this station."33

Army occupational therapy grew in breadth and depth following its introduction into the military medical program during World War I. Having been primarily planned in 1917 as a bedside occupation pro-

30Records do not indicate that Major Montgomery and Miss Montgomery were related.

31Forty-four occupational therapy aides graduated from 1924 to 1933.

32Patterson, R. U.: Remarks to the Graduating Classes of Dietitians, Physiotherapy Aides and Occupational Therapy Aides at the Army Medical Center, June 29, 1933. Occup. Therapy 12: 365-371, December 1933.

33Letter, Col. P. W. Huntington, MC, Army Medical Center, to The Surgeon General, 30 Jan. 1934, subject: Reopening of Hospital Training Courses for Aides in Occupational Therapy, Physiotherapy and Dietetics, 1st indorsement thereto.

94

gram of craft instruction to convalescent orthopedic patients for cheer up purposes, it developed into ward and clinic treatment programs,

95

professional in nature, purposely directed toward maximum restoration of mentally or physically disabled soldiers. The ward and clinic concept continued during the peacetime period, the program gradually becoming more and more limited in scope as cutbacks in personnel occurred because of the decrease in funds authorized for hospital operation.

In general, throughout this period, supplies were obtained through the Medical Supply Division and local purchase channels, and the disposition of articles remained as it had been during the war period.

The Walter Reed General Hospital program had its largest physical expansion in 1927 when six shops were designated for treatment of physically disabled patients in addition to a shop for treatment of neuropsychiatric patients. After the economy cut in 1933 and throughout the peacetime period, the only shop facility retained at this hospital was in the neuropsychiatric area. Conditions other than neuropsychiatric were referred for specific treatment to this shop by the medical officers on the wards. Progress notes were written on these patients and sent to the medical officer concerned.

A general and a neuropsychiatric clinic were maintained at Fitzsimons General Hospital, Denver, Colo., before the economy cut. Both clinics were closed as of June 1933, reopened in February 1934, and continued to function on a limited basis throughout the period covered by this chapter (1917-40).

The annual reports from Letterman General Hospital, San Francisco, Calif., show that by 1920, reduction of occupational therapy personnel had curtailed all but the activities in the neuropsychiatric section. In 1927, the work was extended to all patients in the hospital who could be benefited by it. In 1932, a large centrally located room was designated for the treatment of ambulatory and wheelchair patients and the work in the neuropsychiatric section continued. The cutback of 1933 necessitated confinement of service to the psychiatric and general wards. In 1936, only one aide was available, and the work was restricted to patients in the neuropsychiatric section. Reports of the remainder of the peacetime period indicate that occupational therapy continued to be centered largely in the neuropsychiatric section.

The Fort Sam Houston Station Hospital (later Brooke General Hospital) conducted occupational therapy programs until June 1926 when these were discontinued because of a decrease in operating funds. The 1922 annual report from Brooke General Hospital indicated that occupational therapy was used in the general wards and in the psychopathic section. The annual report for 1926 stated:

It is regretted that the shortage of funds necessitated discontinuance of the Occupational Therapy work during the year. This work was of inestimable value in connection with the care and treatment of neuropsychiatric cases and the bedridden cases of tuberculosis. It is earnestly recommended that funds be made available during the next year for the employment of two Occupational

96

Therapy Aides so that this important and valuable adjunct to the professional services may be resumed.

In 1932 and 1933, the annual reports of Brooke General Hospital continued to point up the need for occupational therapy: "This form of therapy is particularly useful for nervous and mental cases."

Before World War I, the Army and Navy General Hospital, Hot Springs, Ark., was restricted to the treatment of patients who could benefit from the mineral hot springs for which the location was noted. After the war, although recognized as the center for the treatment of arthritis, all types of patients, except those with pulmonary tuberculosis, were admitted for treatment. Occupational therapy was begun in June 1926 and was discontinued in 1936 because of limitations in funds.

The utilization and value of occupational therapy in the military setting during this period were probably best described by the medical officers who worked closely with it. In June 1924, Maj. Sidney L. Chappell, MC, Chief, Neuropsychiatry Service, Walter Reed General Hospital, wrote:34

The most convincing argument of the efficacy of occupation, in the management of neuropsychiatric cases, is to work with these patients in some mental hospital. * * * Numerous cases can be cited who have been regressed, excited, or depressed, where persistent effort has succeeded in arousing some dormant spark of normal interest.

* * * * * * *

It is common observation that although it may not produce cures, with its aid, recoverable cases improve more rapidly or are raised a little from their regressed or depressed states and as a result can be attacked more easily by other therapeutic means.

In February 1930, Maj. (later Brig. Gen.) Harry D. Offutt, MC, Director of Occupational and Physical Therapy, Walter Reed General Hospital, wrote of the successful employment of occupational therapy in the treatment of patients with empyema, pneumonia, tuberculosis, mental illness, defective sight and hearing, amputations, fractures, and cardiac conditions and stressed some precautions to be observed.35 Major Offutt pointed out that, although activity for patients is thought of as being either mental or physical, one rarely exists without the other. He acknowledged the benefits of diversion and brought a different perspective to this facet of activity:

Many patients do not feel at first that they are able to work as we usually think of the term; the pleasure-producing activity makes a stronger appeal. The psychology of the patient is considered and the suitable activity supplied to him, so that from his viewpoint it is diversion. From the therapist`s viewpoint it is well planned treatment.

34Chappell, S. L.: Occupational Therapy for Neuropsychiatric Cases. Arch. Occupational Therapy 3: 213-215, June 1924.

35Offutt, H. D.: Occupational Therapy in a Military General Hospital. Occup. Therapy 9: 1-10, February 1930.

97

In September 1932, Capt. H. M. Nicholson, MC, Director of Physical and Occupational Therapy, Walter Reed General Hospital, in an address to the members of the American Occupational Therapy Association at their 16th annual meeting, indicated that occupational therapy as a part of the patient treatment program could generally be utilized in three different areas: "(1) the chronic general medical and surgical case, (2) the neurological and orthopedic grouping, and (3) the neuroses and psychopathic classes." Captain Nicholson also stressed the assistive role of the occupational therapist,36 "to help the usual medical, surgical, and physiotherapy treatment achieve a complete and useful end-result."

By the late 1930`s, the entire basis of international relations founded upon the Treaty of Versailles was disintegrating. In September 1939, Germany invaded Poland and, subsequently, England and France declared war on Germany. This had immediate effects upon the United States and its military departments. The President declared a limited national emergency on 8 September 1939 and the buildup in the strength of the Army began.

Inasmuch as funds appropriated by Congress during the peacetime period for Medical Department construction had barely covered more than essential maintenance of hospital buildings, expansion of hospital facilities was a primary concern. Reserve equipment was either deficient or obsolete.37 Closely correlated with this was the necessity for a proportionate increase in the number and kinds of personnel required for effective operation.

Throughout the years, it had been suggested to The Surgeon General that military status should be given to dietitians, physical therapists, and occupational therapists. (See Chapter 1, pp. 3-5.) Legislative efforts to achieve this were begun in 1939. Occupational therapists were included in the initial bill (S. 1615, 76th Congress, 1st Session) on which no congressional action was taken, but were omitted from the subsequent bill (S. 3318, 76th Congress, 3d Session) which was introduced in February 1940 but was defeated. In reply to an inquiry regarding this omission, in April 1940, The Surgeon General stated:38

Only nine occupational therapy aides are now employed in military hospitals. Of this number, one is provided for the military, two for the Civilian Conservation Corps, and six for Veterans` Administration patients. It, obviously, would be undesirable to include in the bill a provision for occupational therapy aides when there is only one employed for the military patients.

36Nicholson, H. M.: Why Occupational Therapy in Military Hospitals? Occup. Therapy 12: 37-42, February 1933.

37Smith, Clarence McKittrick: The Medical Department: Hospitalization and Evacuation, Zone of Interior. United States Army in World War II. The Technical Services. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1956, p. 6.

38Letter, Maj. Gen. James C. Magee, The Surgeon General, to Everett S. Elwood, President, American Occupational Therapy Association, 1 Apr. 1940.

![]()